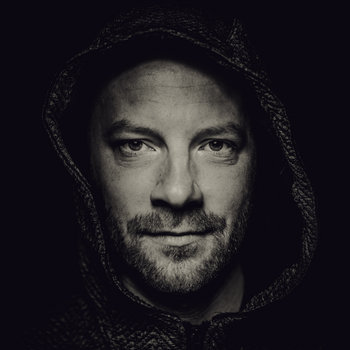

“I’m trying to do this thing where I fill this pan with water and then play the sopranino or soprano into the water, and kind of [get] the little bubbles and different qualities that way,” says Patrick Shiroishi, describing his most recent experiments with his saxophones. He shrugs and smiles. “Hopefully, I could record something like that.”

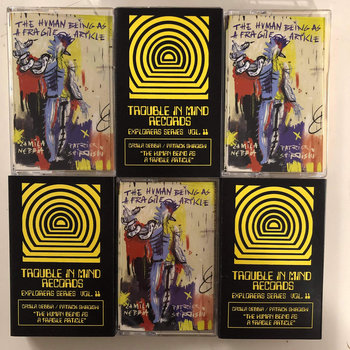

Cassette

When Adolphe Sax designed his family of saxophones in 1846, he wanted to create a new orchestral staple with “a character closer to that of string instruments, but that would have more power and intensity than they have.” He probably wasn’t intending for them to be played underwater. But the Belgian inventor—who dreamt up 46 patents and a dizzying array of inventions, including a giant mortar called the ‘Saxocannon’—led an eventful life, so maybe he’d be happy that his greatest legacy has done the same.

Shiroishi and other radicals are just the latest set of musicians to mess around with reeds. Sax’s creation was largely confined to military bands after middling interest from the classical world, despite the support of composers like Hector Berlioz. It became something of a novelty instrument—one 1916 Vaudeville act used saxophones to mimic squawking chickens—before finding a home as part of Dixieland ensembles and jazz big bands. Charlie Parker’s experiments with “The Devil’s Horn” led him to develop bebop, a revolution in jazz. Eventually, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane (and others) would harness reeds to blow up Parker’s blueprint again, freeing jazz from structure entirely.

“I thought that noise was the logical extension of free jazz, in terms of making music that’s very abstract,” says Lea Bertucci, who plays saxophone and bass clarinet. She grew up listening to her father’s Coltrane albums, but her own music is better placed adjacent to free jazz. She strips her instruments of their most obvious qualities by running them through effects and software or playing them in unconventional ways. As a child, she remembers failing a standardized musical aptitude test when trying to join the school band. “Maybe people who are familiar with my music now are not so surprised by this,” she adds.

Bertucci emphasizes the importance she places in “unlearning” and “trying to get past the jazz and classical training that was very much under my fingers.” Other reed players, like Poland’s Waclaw Zimpel, have used their formal training to explore new forms. A classically trained clarinetist, he moved through the European free jazz and improv circuit, but when it came to his solo work, he landed elsewhere. “I wanted to do something very intimate,” he says, describing the circumstances around the recording Lines, released in 2016 on Instant Classic. Tired of the “high-energy playing” of free jazz, he pivoted to a sound rooted in minimalism and repetition, layering and overdubbing his clarinet recordings. He also found innovative ways to recreate his compositions live, starting with a set of mechanical hammers for piano (“It would have been offensive to ask a properly trained musician just to repeat certain notes!”) as well as an influx of electronic elements.

Since that auspicious start, his albums, both solo and in collaboration—he’s worked with an Indian classical ensemble as Saagara and paired with cerebral electronic producers Shackleton and James Holden—have expanded his sound further. “With time, I started bringing in all those free jazz aspects of my language again,” he says, “And trying to combine them with minimal repetitive music with Indian influences.” His latest album, Massive Oscillations, was partially recorded at Willem Twee studio in Den Bosch, Holland using “very old synthesisers and oscillators,” the kind that “were not meant to be musical instruments.”

Bertucci and Zimpel both make use of electronics and computers to manipulate acoustics, but they also coax unfamiliar sounds from their instruments using what they refer to as “extended techniques.” “It basically means playing your instrument wrong,” says Bertucci, noting that she prefers the term “timbral techniques” which is more inclusive and less westernized. This can mean anything from alternative fingerings, overblowing and circular breathing (continuous notes achieved by breathing in through the nose and exhaling through the mouth and into the instrument) to placing microphones in unusual locations.

Or even stranger ideas, like the stuff that Patrick Shiroishi dreams up in his kitchen. “The other day I was making rice and was thinking ‘Oh—maybe I could put rice on a snare drum and then play into the snare drum, and maybe it’ll bounce and resonate’.” He credits John Zorn’s album Electric Masada as a jumping-off point for his own experimentations: “That was kind of a black hole into really digging into all the possibilities of the saxophone.”

On his 2020 album Descension, Shiroishi ran his saxophone through pedals, looking to amplify the reed. “My idea was for it to be like a saxophone black metal record,” he says, and the album does capture some of the nerve-shredding intensity of the genre, while also finding room for a more plaintive and emotive voice. Shiroishi is too prolific to stick to any one style, though; he released 16 recordings from various projects in 2020 alone, with six more under his belt as of this writing. He plays dewy morning jazz as part of a quartet, runs a ten-piece free improvisation ensemble and still manages to find time to collaborate with all manner of people, from childhood friends to newer acquaintances like sound artist Claire Rousay. “There are so many people who are trying different things,” he says. “I think that’s an inspiring place to be in.”

With that in mind, here are nine albums that will expand your own idea of what a saxophone or clarinet could sound like.

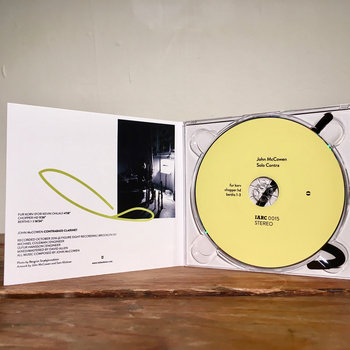

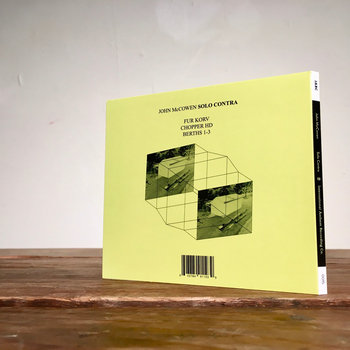

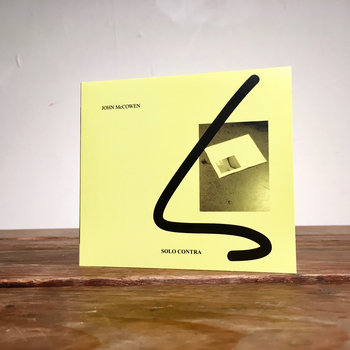

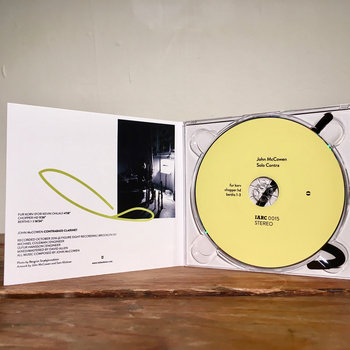

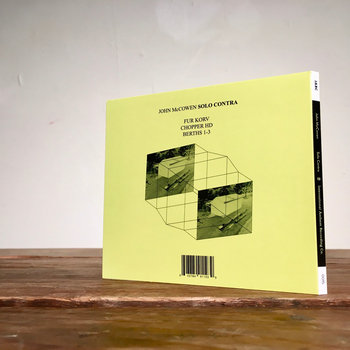

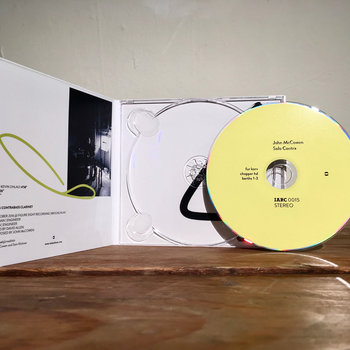

John McCowen

Solo Contra

Compact Disc (CD)

John McCowen’s musical career has carved a path from hardcore punk (he switched to playing saxophone after nearly ruining his voice fronting a band) through weirdo stoner-pop (as a touring reed player for Tweak Bird) and art splattered un-pop (Wei Zongle). As a solo artist, he studied under Art Ensemble of Chicago and AACM’s Roscoe Mitchell, gravitating towards the bass clarinet.

Those references don’t really help when describing Solo Contra, a three-part (mostly) tonal meditation more indebted to the work of musique concréte and drone pioneers like Eliane Radigue. McCowen produced these dense drones entirely acoustically, by placing thirteen different microphones on the bulbous body of a bass clef clarinet. At times the sound rings like gongs or hums like a sine wave, while at others, it seems to make the air itself vibrate.

Saagara

2

Already a devotee of Indian music, Waclaw Zimpel met ghatam (an open-necked pot played as percussion) player Giridhar Udapa after a concert in Warsaw in 2012 and asked him where to study Indian music. “And he said right away, ‘Come to Bangalore’ where he lives.” A few months later, Zimpel flew to the city and spent a month studying ragas with a flute master. Within a year, he formed Saagara with Udapa and three other classically trained musicians from Bangalore.

“There’s a lot of collaborations between different cultures, which are only about being on the same stage, and looking nice together,” says Zimpel, “and when the parts are not well integrated, to me, it doesn’t make any sense.” Their first album found Zimpel struggling to play Indian classical standards (“Their way of thinking about the rhythm is so complex and so different to what we are used to in the West, it was really frustrating, like going back into kindergarten!”) but on their second album, the musicians find a common language. Zimpel’s saxophone soars and glides while Mysore N. Karthik’s violin screams and saws all over the group´s complex, feather-light rhythmic interplay.

Zs

Xe

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

Over more than 20 years of performing and recording, the group formed by tenor saxophonist Sam Hillmer has existed as everything between a sextet and a duo. What hasn’t changed is Zs‘ shape-shifting approach to music, the kind that lends itself to ridiculous use of the hyphen (death-prog, avant-chamber, and many more) They are a band of extremes, juxtaposing disciplined repetition with the wild freedom of improvisation, leaving plenty of room for exploration all the while.

By 2015’s Xe the lineup had stabilised again with Hillmer, guitarist Patrick Higgins, drummer Greg Fox (at that time also a member of Liturgy and Guardian Alien) and Michael Beharie on “electronics.” The result is an album that seethes with a barely contained restraint, long passages of intricate minimalism that burst into bright squalls of noise. While Hillmer can wail with the best of them, most of the time he’s content being a cog in his band’s well-oiled machine, as on the titular 18-minute closing suite.

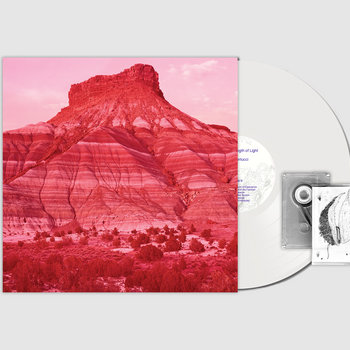

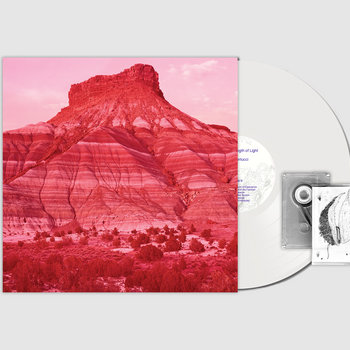

Lea Bertucci

A Visible Length of Light

, Vinyl, Vinyl LP

Lea Bertucci studied visual arts, film and photography in college, which she credits with helping her develop her own musical language. The concepts she came across in experimental cinema, ”really relate to what goes on in abstract music, in terms of creating a disturbance over space-time and organising information over time,” she says.

On A Visible Length of Light, she creates a cinematic “meditation on empathy”, the fullest realization of her merging of classical and experimental sound. At times her reeds (bass clarinet and alto saxophone) trill brightly and clearly; at others they’re invisible, absorbed into the compositions or weighted down with treatments and effects. It’s tempting to think that the lightness at the centre of A Visible Length of Light – an album “guided by the heavy experience of being American, at this particular point in our history” – comes from the air being blown through Bertucci’s reeds and into the compositions.

Sugarstick & Xerox

S/T

The clarinet can be as piercing and cutting as any piece of electronics in the right hands, which made it a firm favourite of industrial and post-punk groups (most notably Cabaret Voltaire). “Even though you have a very loud drummer, it is always possible to find a range of frequencies, where the drums don’t exist,” says Waclaw Zimpel.

While Zimpel was thinking in terms of free improv bands, where he initially struggled to make himself heard, he’d doubtless approve of clarinettist Tom Jackson’s work as part of a trio with Luke Calzonetti (synthesisers) and Brendan Dougherty (drums) for this Opal Tapes release. Using both bass clarinet and clarinet, Jackson cuts through the sparse thicket of sound his bandmates generate. On one track he’ll squall like a free jazz musician, while on another his reed will sleazily leer. Whatever he does, it seems to find the space between Calzonetti’s bleeps and chirps and the off-kilter thumps of drum skins.

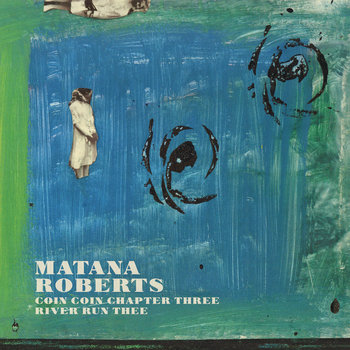

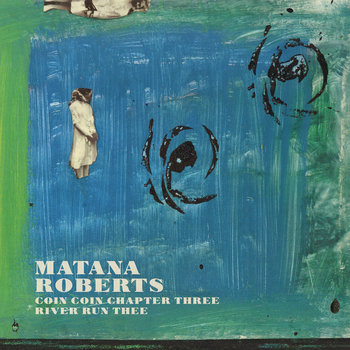

Matana Roberts

Coin Coin Chapter Three – River Run Thee

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

River Run Thee is the third edition of American saxophonist Matana Robert’s four chapter Coin Coin suite, which unflinchingly documents African-American history in the United States. Each edition has a specific character: from the rich, grand ensemble of Chapter Four: Memphis to the singular soloing of Chapter One: Gens de Couleur Libres. Inspired by a solo research road trip through America, River Run Thee is arguably the series’ most self-contained entry, a mellow reflective album described by Roberts as a “fever dream.”

The album’s illusory quality is apparent from the start: a soft hum merges into the sound of a distant saxophone heard from another room, as recordings of Roberts’ voice, both singing and speaking, create a tapestry of sound. Throughout the album, the horn itself often takes a back seat to her recitals of spoken word, or the electronic drones that fill the record like cicadas on a humid night. Roberts’ music is in the lineage of free jazz – the music of African-American liberation – but it extends the form beyond the screaming solos of her forebears.

Patrick Shiroishi & Dylan Fujioka

No-No / のの

Collaboration is the one constant in Patrick Shiroishi’s vast discography, and he’s been playing with drummer and percussionist Dylan Fujioka since their days in high school. The pair share more than just a friendship and a love of freeform improvisation though: both their grandparents were among the 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly interned in camps during the Second World War, for nothing more than the simple fact of being Japanese.

Shiroishi has increasingly begun to document this ugly part of American history (A track on Descension is named ‘Grandchildren of the Camps’), which has been largely swept under the rug. Shiroishi remembers asking his grandmother about it while he was at high school, after finding a tiny paragraph on the subject in one of his text books. She shut down and didn’t want to talk about it. “I think it’s very Japanese of people to not talk about that kind of thing. It’s always: keep your mouth shut, work hard, move forward.”

These improvisations, recorded at Fujioka’s house, is one of an increasing number of recordings that Shiroishi has dedicated to his grandparent’s story and to highlighting anti-Asian racism today. It’s a surprisingly quiet, subtle set that showcases the curious way the duo explore their instruments, like children sneaking around the house after dark.

Wax People

Wax People

The guttural growl of the saxophone lends itself well to the more visceral and extreme fringes of experimental music: the groundbreaking work of Peter Brötzmann and John Zorn, for example. Unsurprisingly, fewer heavy artists have made use of the clarinet – Toby Driver’s long-running experimental metal/un-metal act Kayo Dot being a notable exception.

Los Angeles’ Wax People buck the trend by incorporating a bass clarinet into their taut four-piece. It’s such a natural fit for their stop-start sound, all cascading breakdowns, duelling reed-guitar interplay and multi-layered riffs, that you wonder why no-one thought of it before. The bass clarinet isn’t just along for the ride—it’s the muscular protagonist of the band’s dense yet precise sound. There’s something of the grinding cult Italian power trio Zu (who featured a baritone sax instead of a guitar) in the way the reed cuts through the murk, but Wax People also wail and howl like a true metal band.

Ashley Paul

Ray

Vinyl LP, Poster/Print

Former Yellow Swan Pete Swanson recalls Ashley Paul making “hardened noise guys’ hair stand up on the back of their necks” the first time he saw her play. Anyone who has seen Paul live will understand exactly what he means. She deals in the kind of abstract, intimate fragility that sends shivers down spines: hushed vocals that fall in and out of tune, a slightly awkward use of space and pace, and a disarming use of quiet.

Ray, put together remotely during 2020 with the help of double bassist Otto Wilberg and bass clarinetist Yoni Silver, leans further into the playful qualities that have always been present in her work. The gentleness of the album accentuates each scratch, squawk and squeak, each intake of breath and pause for thought. Gently distorted lounge jazz, heard in a waking dream, segues into half-formed lullabies which dissolve into almost pop songs. Ray is proof that the best experimental music often seduces your attention rather than loudly demanding it.