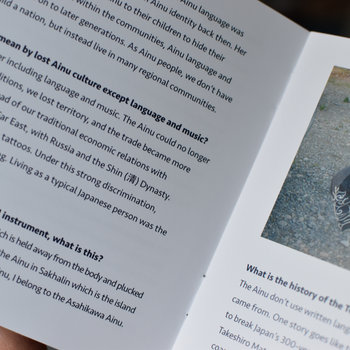

The original settlers of Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, the indigenous Ainu—a name derived from the word meaning “human” in their native language—are believed to have made their home there sometime in the 12th or 13th century. They lived quiet lives as hunters and foragers, communing closely with nature, guided by the belief that everything natural—human beings, flora and fauna, even the elements—possesses a kamuy, or divine spirit; there are ceremonies and rituals to honor each deity. Music is critical in their culture; they have songs for work, play, sharing stories, and settling arguments. In fact, it’s so entrenched in the Ainu way of life that their broad descriptions of sound include the “musical” among the “non-musical” with no particular distinction. The term haw (meaning “voice”) includes the vocalizations of humans and animals alongside the sound of instruments, and hum (meaning “sound” or “feeling”) could refer to the percussive sound of drums or the roar of a raging river. To the Ainu, music is as natural as breathing.

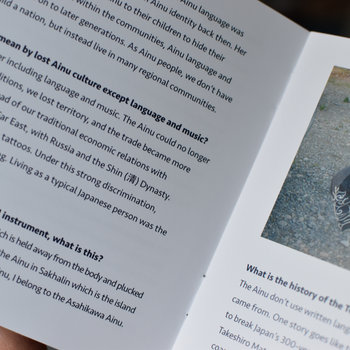

In the 19th century, their peaceful harmony with nature would be interrupted by the same destructive force that has been the bane of indigenous groups all over the world: colonial expansion. Following the Meiji Restoration, which consolidated Japan’s disparate political factions under the banner of a single Emperor, the nation turned its attention to military might and expansion. Before long, they colonized Hokkaido, displacing the Ainu people from their ancestral lands. The Ainu were forced to become Japanese citizens, and the use of their language was outlawed along with their cultural practices. The 1899 law that stripped them of their rights wasn’t formally repealed until 1996, though parts of it were stricken over time through tireless advocacy. Nevertheless, the government’s attempts at cultural erasure proved mostly successful; most people of Ainu descent had fully assimilated into Japanese culture, many of which were oblivious to their heritage. Today, the number of people practicing “pure” Ainu culture is estimated to be in the hundreds; the number of people fluent in the language may be fewer than ten.

However, the Ainu have proven to be resilient. Elders have steadfastly held onto their knowledge, passing it down through oral tradition. Interest in preserving the culture has seen a significant upswing as archival efforts ramp up and universities and museums make scholarly documentation more accessible to the general public. In 2019, the Japanese government finally took steps to recognize the Ainu as indigenous people by passing a bill that aims to make society more inclusive for them. While the law isn’t perfect—notably, it lacks an apology for generations of mistreatment, which activists have criticized—it shows that the tide continues to change.

Most importantly, the Ainu people are adaptable. As their culture continues to increase in visibility, more and more Ainu are embracing their heritage and showing that it still deserves a place in the world. Here are some modern Ainu artists that honor their past while lighting a path forward for their future.

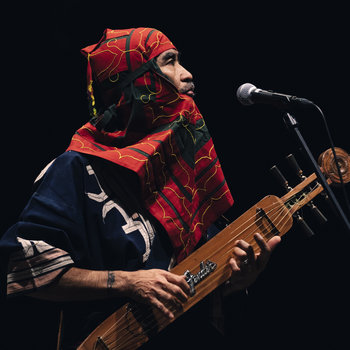

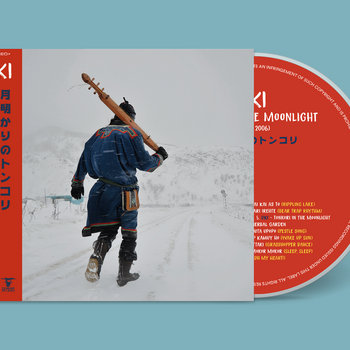

OKI

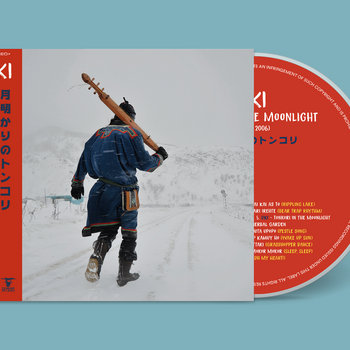

Tonkori in the moonlight

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Born and raised in Hokkaido, Oki Kano (commonly known as simply OKI) didn’t learn of his Ainu lineage until he was old. When he finally met his father—the renowned wood sculptor Bikki Sunazawa, who brought awareness to Ainu tradition through his art—he felt a deep fascination and wanted to learn more. Though some Ainu rejected him for growing up outside of their community, the experience was nonetheless formative.

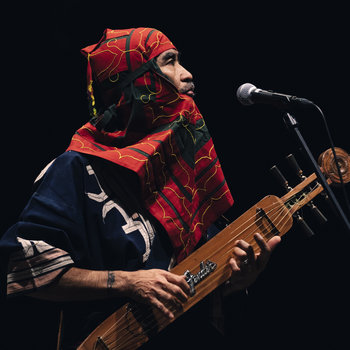

Frustrated and feeling like an outsider both to Ainu and Japanese culture, Kano decamped to New York in the late ‘80s. There, he made friends with several Native Americans during a time when there was strong momentum behind a movement for their rights to be recognized. This was another pivotal moment for Kano, and it inspired him to make a stronger push to connect with his heritage. After returning to Japan in 1993, he started to learn the tonkori, a zither-like stringed instrument that had long been considered an outmoded aspect of Ainu culture. There were no tonkori teachers to show him the ropes, so he taught himself by listening to old cassette tapes. When his friend, Navajo flutist R. Carlos Nakai, visited Japan later that year, Kano played the tonkori for the first time in a recording on his album Island of Bows.

Since then, Kano has become an ambassador for Ainu culture in much the same way as his father, introducing long-forgotten sounds to new audiences. Though he’s passionate about preserving and proliferating Ainu music, he’s not a staunch traditionalist. On this career-spanning retrospective, he performs traditional songs alongside other indigenous music, reggae, and even a Celtic folk ensemble. It’s a fitting statement on where Ainu music stands—floating amidst a sea of disparate cultures, vying for its place.

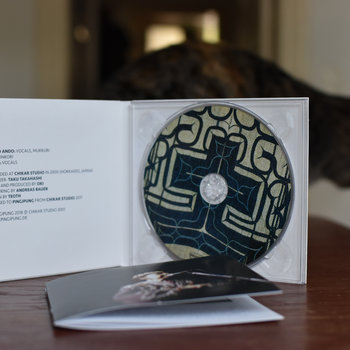

Umeko Ando

Ihunke

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Kano’s commitment to preservation extends far beyond his own music. In the late ’90s, he linked up with Ainu elder Umeko Ando, a vocalist and expert player of the mukkuri, an idiophonic instrument similar to the jaw harp. Her appearance on OKI’s 1998 album Hankapuy brought increased attention to Ainu singing, and they decided to record an album under Ando’s own name. Ando’s delicate, undulating vocals make it clear that she was getting on in her years, but she delivers a beautiful performance of the traditional songs she’s spent her life perfecting to the accompaniment of Kano’s tonkori.

The album was a learning experience for both musicians. Kano reined in his playing, taking it slow and following Ando’s lead. Ando submitted herself fully to the process of recording in a studio, something very few elders had done at that point. “Many Ainu hesitate to break with tradition,” Kano said of the sessions. “If Umeko hadn’t been so flexible to work with the younger generation and recording technology, this album would never have happened.” Ando would pass away soon after due to a battle with cancer in 2004, but her mastery of Ainu vocal style was immortalized in these recordings.

MAREWREW

mikemike nociw

Following his work with Umeko Ando, Kano would use his reach to produce albums for some younger artists. MAREWREW, a group composed of Ainu singers and musicians from the Amami islands, would be his first protégé. They perform a type of vocal called upopo, which are group songs performed for festive gatherings. Each song consists of a short melodic germ that’s repeated. Most are performed a cappella, but some incorporate rhythmic elements like clapping or stomping. Some songs are intended as accompaniments to dances or games, and you can feel the exuberance radiating from them—in the last few seconds of “muysoka hanene,” the group bursts into infectious laughter.

Kapiw&Apappo

PAYKAR

Kapiw and Apappo (Ainu performing names meaning “seagull” and “flower,” respectively) are a pair of sisters that learned the songs of their people from their grandmother while growing up in the lakeside village of Ainu Kotan. They also perform upopo, but in a style notably different from MAREWREW, owing to regional differences. Here, the songs have a brisker pace and are more spacious, with occasional accompaniment from tonkori and mukkuri. In a surprising twist, there are even modern amenities like synthesizer and field recordings worked into a couple of tracks.

Oki Dub Ainu Band

Sakhalin Rock

In 2005, Kano formed the Oki Ainu Dub Band to synthesize his two greatest passions: Ainu music and reggae. Growing up near Tokyo, where reggae music was exceedingly popular when he was young, it became his first musical obsession—and it taught him the power of expressing his politics through music. “Bob Marley sang that people who forget about their ancestors are the same as a tree without roots,” Kano told CNN in 2019. “I checked the lyrics as a teenager, though they became more meaningful to me as I matured.” Kano plays his trusty tonkori against a Western-influenced backdrop of guitar, bass, drums, and keyboard, transforming upopo songs of old into heavy dub jams. It’s a public educational service and a lodestar for the future of Ainu sounds, sure, it’s also just the music he loves. By finding a way to reconcile these two parts of who he is, it seems like Kano has finally planted his roots.