Taku Sugimoto is considered a foundational figure in Japanese experimental music, but when he first picked up the guitar in high school, his intention was to use it to make rock ‘n’ roll. He formed a psychedelic rock band called Piero Manzoni in 1985, at the age of 19, but ended up going it alone a short three years later. He turned to session work for a while, contributing his talents to a respectable list of albums that includes Ghost’s Temple Stone and L’s Holy Letters, two albums that are considered peerless classics of Japanese psych-rock. He had a brief stint on the cello, forming an ensemble called Henkyo Gakudan in 1991 that would disband by ‘92, but it wouldn’t be long before he’d put it down for good and come back to the guitar.

After forming his own independent label Slub Music in 1994, Sugimoto would explore new frontiers in playing and improvising on the guitar, turning his focus to interspersing sound with silence and making each note resonate in the listener with a sense of purpose. Sugimoto would cultivate relationships with like-minded people during this period, bringing in collaborators from Tokyo and, eventually, the rest of the world. A friendship he formed with Austrian trombonist and composer Radu Malfatti would prove an important gateway to his discovery of the Wandelweiser collective, a group of composers and performers that utilized silence in avant-garde music in a way Sugimoto had not yet realized was possible. Sugimoto’s relationship with Wandelweiser would be mutually beneficial; his skilled playing and thoughtful philosophical musings on sound pushed them to a brink of possibilities they hadn’t considered either.

Sugimoto’s networking would inspire him to pivot from improvising to composing, and his work would become even more restrained. “For me, interpreting Taku’s music requires a lot of effort and dedication,” says Cristián Alvear, a frequent performer of Sugimoto’s compositions. “His possible realizations are many and each one of them does not exhaust or close the work. One can always go back and make other versions, make new musical objects from it.”

Sugimoto has left his mark on experimental scenes across eras and in multiple countries, appearing on labels like Japan’s Ftarri, the United States’ Erstwhile, China’s Zoomin’ Night, and the UK’s Another Timbre. Below is a list of releases from the many phases of Taku Sugimoto’s rich career, each an expression of his love of endless possibilities.

Taku Sugimoto

DDDD

DDDD is, to anybody’s knowledge, Taku Sugimoto’s first ever release, predating what was previously believed to be his first solo release in 1988. Originally released in 1985 as a small batch of 20 cassettes, Sugimoto has made all these experiments with guitar, objects, and tape available to everyone on Bandcamp. Recorded when he was just 19, DDDD provides a look into the mind of a young Sugimoto that was already starting to develop the disciplined approach to improvisation that he would begin to show us in full 9 years later with his first release on Slub Music. Though his beginnings as a noisy psychedelic rocker clearly come through in the abundance of fuzz and feedback, these recordings certainly do not shred—they are slow moving, spacious, and occasionally very quiet. Especially in the third track, there are shades of the Taku Sugimoto that would come to be known for his virtuosic touch on the guitar that fans out sound the way a painter spreads watercolors with a brush.

Taku Sugimoto

Myshkin Musicu

Originally released in 1996, Myshkin Musicu is Sugimoto’s third solo release on Slub Music and is exemplary of his evolution as a performer in this formative period. The tracks were mostly recorded in the Galerie de Café Den museum and performance space and Sugimoto’s own Slub Music headquarters, with a couple of songs sourced from live shows. The sixth track, recorded at a 1996 show in Chicago, is the only track that features accompaniment; Sugimoto is joined by an ensemble of six other musicians including frequent collaborators Kevin Drumm and Tetuzi Akiyama—whose own solo guitar album, Relator, is also an important touchstone of Tokyo experimental music. Unusual techniques are used to great effect, like playing muted staccato notes or producing a low roar from his amplifier by barely touching the strings of his guitar. Myshkin Musicu stands as a significant release, and the one where Sugimoto begins growing into the style he would become known for—quiet and introspective, but purposeful.

Tetuzi Akiyama / Taku Sugimoto / Toshimaru Nakamura

The Improvisation Meeting at Bar Aoyama

When Toshimaru Nakamura—experimental musician and player of the “no-input mixing board,” an instrument he created by feeding the input of his mixing board from the output and manipulating the feedback—started organizing a show for his friend Jason Kahn who was visiting Tokyo in 1998, he didn’t expect it to become the premier spot for live performance of experimental music. It ended up evolving into a monthly concert series with Nakamura, Tetuzi Akiyama, and Taku Sugimoto at the core. “These three and a couple of guest performers play at the bar once a month,” Nakamura writes. “Five altogether seems to be the maximum due to the size of the room.” Each track is an excerpt of the concert that occurred on the listed date, with most including a guest from Tokyo’s then-burgeoning experimental scene: Sachiko M, Otomo Yoshihide, Utah Kawasaki, Sudoh Toshiaki—the former drummer of Melt-Banana—and more. Many of Taku Sugimoto’s friends and collaborators came through Bar Aoyama, and it would prove pivotal to relationships he would build in the future.

Antoine Beuger

A Young Person’s Guide to Antoine Beuger

Taku Sugimoto met Antoine Beuger—composer, flautist, and founding member of the Wandelweiser collective—sometime in 2008. “He visited a concert I did in Austria, and it was a very long concert,” Beuger says. “I did a piece, it was five or six hours which only consisted of one-syllable words here and there, and lots of silence.” When Sugimoto and Beuger spoke after that show, Sugimoto said that it was highly formative for him. “He ended up telling me that for him, it was important to see that this is really possible—not only possible, but maybe a very fulfilling experience.”

A friendship between Sugimoto and Beuger began to form over the days that followed. “He was very friendly, but also quite a closed person,” Beuger says. “But being together there, the trust built up very quickly. Day by day, he started showing me more of his work—also, his way of notating things, and even his reflection on his work. He reads a lot of philosophy, and also writes. And we kept talking about all kinds of things—everything; about our hidden loves, which composers we secretly love but don’t really tell everybody about.”

“Not long after that,” Beuger continues, “Taku asked me to write a piece for a group of string players to be played with his group of friends.” The piece Sugimoto requested became Tanzaku, spanning tracks 1 through 12 of A Young Person’s Guide to Antoine Beuger. “The CD just arrived at my home—he sent me some copies. I didn’t know he was intending to do a CD.” The album was full of allusions to Sugimoto and Beuger’s conversations during their time together, some of which Beuger didn’t notice right away. “The title, A Young Person’s Guide, is a hint to our conversations about Benjamin Britten,” he says—one of those “hidden loves” they discussed. “The little drawing he made on the cover is a hidden message that I only understood much later.”

“I told him about a little experience I had on a little bench in a forest; it was kind of a moment where I felt a very strong presence of a friend that died not very long before,” Beuger says. “It was not long before I met Taku in Tokyo, and I told him about this.” Only later, when Sugimoto asked Beuger if he recognized the bench on the cover, did he realize what the drawing had meant. The solo guitar piece from tracks 13 to 18, Sekundenklänge, was written to be played at the funeral of Beuger’s late friend.

“In many senses this CD is—of course it’s publicly available—but it’s also a very personal letter to me. It was a way of saying ‘I haven’t forgotten what we talked about,’” Beuger reflects. The two of them have never met in person again since that time, but a bond was formed that will remain with the two of them for the rest of their lives.

Taku Sugimoto & Cristian Alvear

‘h’

Compact Disc (CD)

“This piece was originally composed for Songs,” Sugimoto writes, “a duo project with Minami Saeki, a female singer who I have been working with recently.” The title of the piece, which is one letter, is named that way simply because Sugimoto is not very interested in coming up with titles. “The titles of the pieces I write for Songs are especially simple: a, b, c…, or I, II, III…, or 1, 2, 3.” The piece is peculiar among Sugimoto’s recent output because it contains very little silence and focuses heavily on melody—a sign of his shifting interests. “I often think that some pieces I compose these days are no longer avant-garde,” he says, though ‘h’ certainly still sits squarely in that category. “The piece was recorded during a concert we gave as a duo in Ftarri on November 4,” says Cristián Alvear, who performs the piece alongside Sugimoto. “I remember the date because my dear friend Hoshi was there and it was his birthday. That’s why Taku and I decided to dedicate the release to him.”

Manfred Werder stück 1998

stück 1998

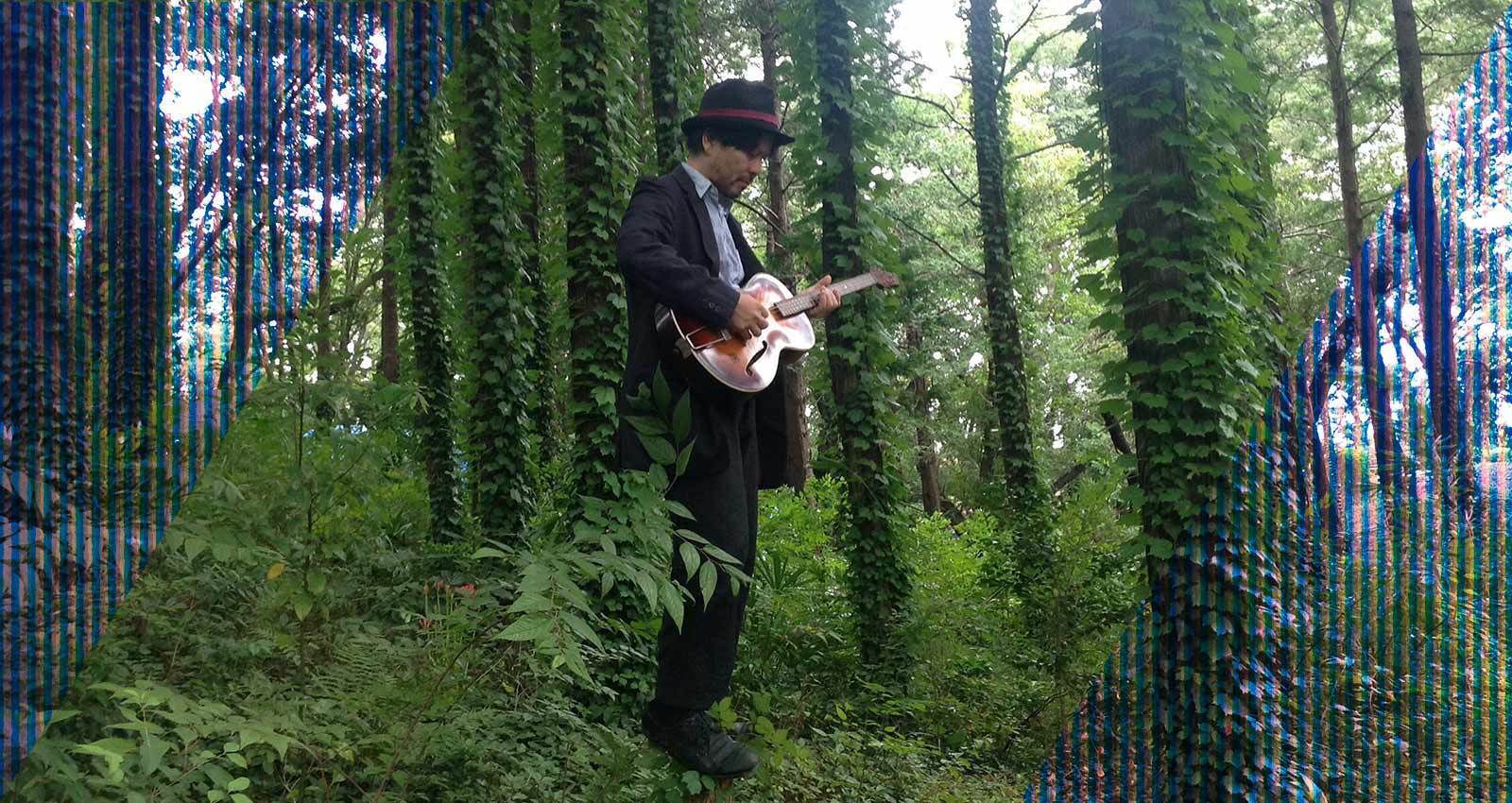

Antoine Beuger describes the Wandelweiser collective as a “chaotically expanding tissue” whose only binding glue is friendship. “There is no center, there is no institution, there is no membership.” There is perhaps no better Wandelweiser composition that exemplifies this philosophy than Manfred Werder’s stück 1998 seiten 1-4000 (translating roughly to “pieces, pages 1 to 4000”), a piece which must be outsourced all over the world to even have a chance at being performed. It is a gigantic 4000 page tome of a musical score that would last 533 hours and 20 minutes if performed consecutively, though having one person perform the whole thing was never the intention. Werder has been distributing pages to musicians since 1999, allowing the piece to slowly become realized over a very long period of time. Werder prefers, in his own words, “actualizations” to performances, giving musicians the freedom to interpret anything that’s not specified in the score however they choose—sure enough, the cover reads “actualized by Taku Sugimoto.”

Stück 1998 has no mandate on what instruments should be played, so Taku Sugimoto brings his signature weapons of choice: guitar, mandolin, and a 6-string bass. Sugimoto performs pages 947 to 957, and records outside so that the sounds of his environment become part of the piece. You hear chirping birds, cars zooming by, children playing, and Sugimoto plinking along the ten pages of this slice of the composition that he’s been tasked to leave his permanent mark on. The loose web of Wandelweiser is given life by the very nature of stück 1998, and is a perfect analogue for the niche that Taku Sugimoto has carved for himself.