Loren Mazzacane Connors has yet to appear in any of Rolling Stone’s sporadic lists ranking the world’s 100 greatest guitarists. But since the late ’70s, Connors has become one of the instrument’s truly singular voices. Whether improvising meditative solo pieces or collaborating with any of his dozen duet partners, Connors’s vision of warped, gestural blues is instantly identifiable, from his first wobbling note or even a trickle of tape hiss. It sounds like nothing else.

“I don’t know shit about music,” says Connors, 71, from the Brooklyn apartment he shares with his wife, collaborator, and editor, the singer Suzanne Langille. “I don’t even know how to tune a guitar. I took music lessons as a kid, but I forgot it all. It just comes out of me. I get amazed at my own self.”

In 1991, just after his move to New York from New Haven, Connors was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Encouraged by Langille, he had just entered a new musical phase where he began approaching the guitar as an improvising composer, as if shaping songs from thin air. In the 30 years since his diagnosis, he has become wildly prolific in that way, releasing dozens upon dozens of albums, singles, splits, compilations, and reissues. “When I’m high on my pills,” Connors quips, softly, “my hands move faster than most people’s hands.”

It is a labyrinthine mess of work, with series that start and stop, motifs that vanish and reappear, and ongoing collaborations that crisscross decades. But by and large, Connors’s music ponders the gorgeous melancholy of existence, his pieces like diary entries rendered in enviable prose.

Another key theme of Connors’s music is its constant sense of newness. Over the years, he has collaborated with a string of marquee players, from Jim O’Rourke and Keiji Haino to Daniel Carter and Christina Carter. He often begins these relationships knowing very little about the musician he’s meeting. When he convened with Australian sound artist Oren Ambarchi in New York in 2017, for instance, he didn’t really care what kind of music Ambarchi played or how he even used his pedals to make it. The result, “Ronnel,” is the centerpiece of Leone, their debut together. The sound is tense, almost frayed—another emotional distillation in a career of them.

“This has nothing to do with scales or knowing how to write or read music,” he says. “You make the sounds you need to make.”

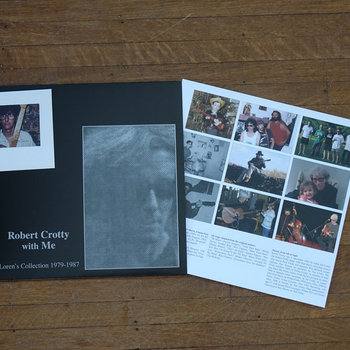

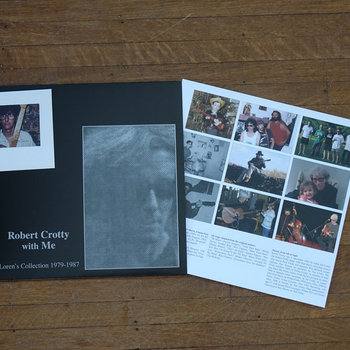

Robert Crotty & Loren Connors

Robert Crotty with Me: Loren’s Collection 1979–1987

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

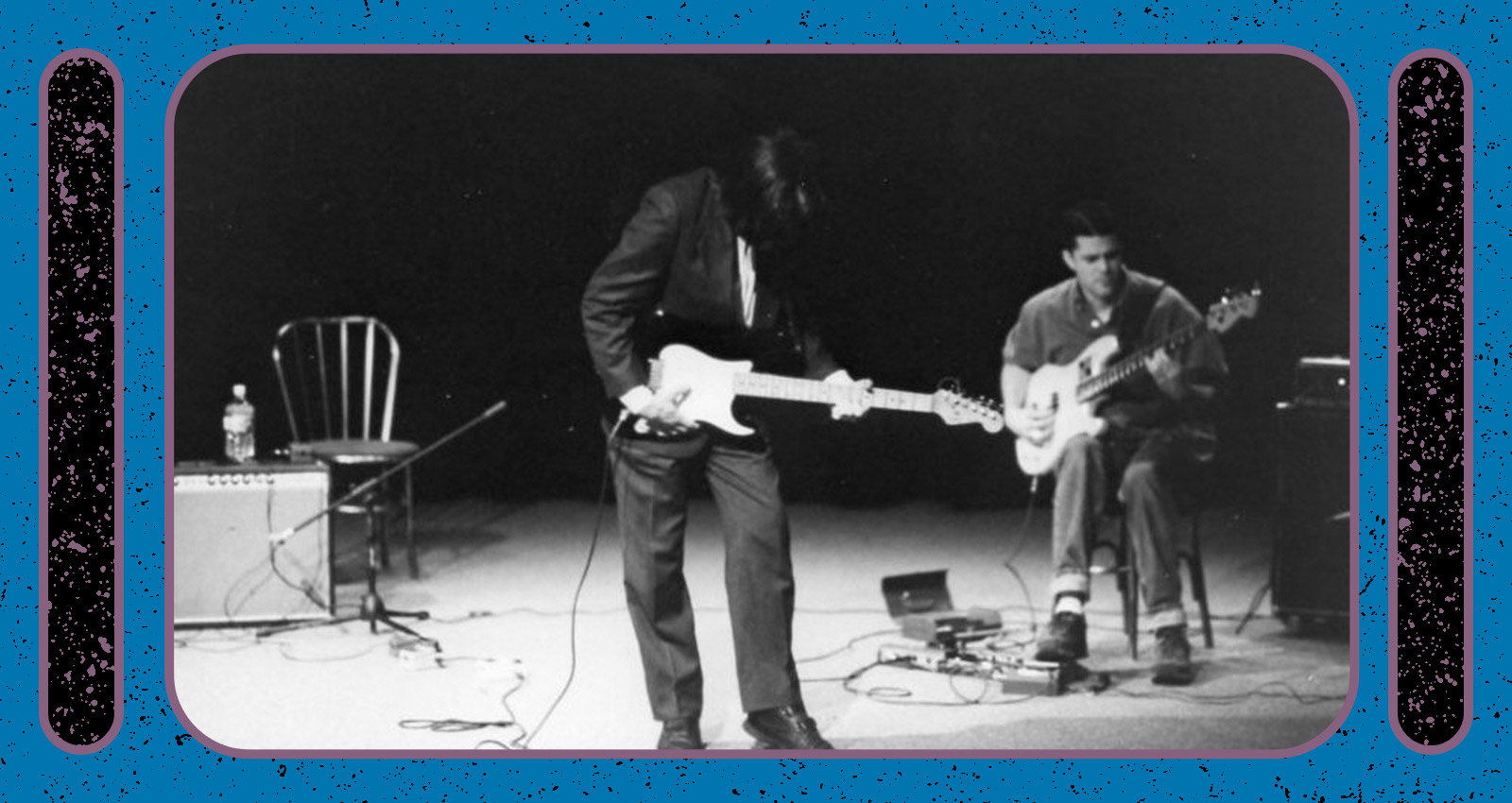

Connors is best known for his prismatic improvisations, abstract pieces that stack the building blocks of songs in unexpected ways. But where do those basics come from? After childhood violin lessons and a stint with the trombone, he finally picked up a guitar around the age of 16. Years later, he met a fellow New Haven townie named Robert Crotty, a blues aficionado who’d been playing since he was six. In the ’70s, Crotty would arrive unannounced at the small office Connors had turned into an apartment. Trading acoustic licks and staring out the window, they’d swap classics for hours—Blind Willie Johnson, Jimmie Rodgers, Ray Charles. “He didn’t show me anything,” Connors remembers of Crotty, who remained a New Haven staple until his death in 2011. “I just picked it all up from him.” Oftentimes, the tape was rolling.

Issued in 2017 alongside a brilliant set by Crotty’s electric band, Robert Crotty with Me captures the camaraderie of those sessions and Connors’s budding intensity as these two white kids from New England try on the country blues. In “Improvisation No. 2,” you hear the ghostly moan that would become a Connors hallmark. A take on “Come Back Baby” embodies the negative space and a sense of the room’s sound that define Connors’s essential work. The real highlight, though, is a modest version of Eric Clapton’s “Golden Ring,” a heartsick ode to doomed romantic persistence. Recorded to crackling tape with a kid clamoring in the background, it sounds bedraggled and honest, as if Crotty and Connors are clinging to the words like a last hope.

Loren Connors

Unaccompanied Acoustic Guitar Improvisations Vol. 10

Vinyl LP

Around the time Robert Crotty was showing up at Connors’s door, Connors was at the start of a wildly prolific period. Between 1978 and 1980, Connors issued nearly a dozen albums, most of them part of a self-made series dubbed Unaccompanied Acoustic Guitar Improvisations. Frenetic, but absolutely focused, Connors uses inherited blues themes and techniques as fodder for longform extemporaneous takes. He snaps strings and slides across them, bleating with an affected blues moan. “They’re kind of hard to take—all the hollering in the background,” Connors says of that early music, now being reissued by Feeding Tube. “But I’m glad it happened that way. I’m glad I didn’t stay like that. No one told me to stay like that.”

In 2019, Blank Forms added a tenth volume to that series by issuing a long-lost tape of Connors performing in Woodstock during this period. Though the vernacular is deeply rooted in the sounds of the American South, the spirit recalls the vital transatlantic action of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble. Connors sings to his ideas, following them as though delivering a duet on a delay. It is neither dreamy nor spectral like the work that would soon follow, but it is intensely gestural, a rush of ideas trying to cut to the quick of a feeling.

Loren Connors

The Departing of a Dream Vol. III: Juliet

Compact Disc (CD)

In the early ’70s in New England, Connors would go see Miles Davis, then in the throes of his almighty electric band, every chance he had. The way Davis held notes enchanted Connors. More than a quarter-century later, he emerged with a tribute of sorts for Davis: The Departing of a Dream, a long-running series indebted to “He Loved Him Madly,” Davis’s own astral ode to the late Duke Ellington. For two decades, Connors has reserved some of his most somber and elegant music for the ongoing Departing of a Dream sequence, which hit seven volumes in 2019. Perhaps more than anything else Connors has made, these pieces actively acknowledge their own impermanence, notes left to fade like smoke from a fire’s dying embers.

First released in 2004, Vol. III: Juliet epitomizes that approach with the help of a tragic love story so familiar it might seem trite. But this five-piece suite voices Juliet’s epochal turmoil—the hope, the hurt, and the end. “Her Love,” the 21-minute opener, captures the feeling of grasping at something forever out of reach. The four miniatures that follow trace Juliet’s sad descent into history’s annals. Connors’s playing is tender and lyrical, acknowledging the sweetness at work—the brief farewell, “In Lover’s Eye,” is one of the prettiest pieces of solo guitar music ever made. Close your eyes while listening on headphones: Notice the way you can almost picture the shape of the room Connors is in? It’s his uncanny way of reminding you that this moment is fleeting, too, same as the rest.

Loren Connors

Blues: The “Dark Paintings” of Mark Rothko

Vinyl LP

Before Connors became serious about playing music, he studied visual art at a state college in New Haven. In 1970, his longtime teacher, a burly sculptor named Michael Skop, introduced him to the paintings of Mark Rothko, the color field visionary whose deceptively complex planes of color could tap hidden wells of feeling. (At 71, Connors remains a busy painter and poet.) That same year, Rothko committed suicide after working on his so-called Dark, or “Black on Gray,” Paintings—muted shades of gray on canvas, squaring off in big desolate blocks. The images stuck with Connors and dovetailed two decades later with Suzanne Langille’s advice. “When we met, I liked his piano playing more than his guitar playing, because I could hear the composition,” she remembers. “I told him to stop thinking of himself as a guitarist and start thinking of himself as a composer.”

That prompt led to dual breakthroughs—1989’s In Pittsburgh and 1990’s Blues, his poignant response to Rothko’s farewell works. Originally self-released in an edition of 300, Blues remains one of the most striking records of Connors’s career. It is, as the title and inspiration suggest, a study of shadow and sadness. The high notes of “Blues No. 5” arrive as an endless succession of sighs. “Blues No. 2” floats like a wail on the wind, immense suffering tempered by worldly exigencies. But there’s a sense of quizzical wonder to these little melodies, as if Connors finds it just as easy to be amused by difficulties as exasperated by them. It’s ultimately bittersweet, like finding an artist who changes your perceptions the year he takes his life.

Loren Connors

As Roses Bow: Collected Airs 1992–2002

There are nearly a dozen Connors compilations, meticulous attempts to tug at any one of the several threads that wind through his career. His early work with Kath Bloom has been bundled, as have those formative years on Daggett Street in New Haven; Night Through is a sprawling career retrospective, current through 2004. But none of these sets rival 2007’s exquisite As Roses Bow in cohesion, beauty, or accessibility. Culled from a decade of albums by his longtime label, Family Vineyard, As Roses Bows gathers 43 airs—that is, little songs with a distinct melodic core, or, as Connors puts it, “a tune.” They feel unforced and vulnerable, snapshots of deeply reflective moments. “I didn’t do anything—they just fell out of me,” says Connors. “They were the most effortless thing I ever did.”

Connors heard stories about Ireland as a child from his father’s side of the family. With those tales came traditional Irish airs, especially those of prolific 17th-century songwriter Turlough O’Carolan. Connors began committing his own versions to tape in 1992, a year after his Parkinson’s diagnosis. Most of these airs last less than two minutes; almost all of them, like the beguiling “Brigid’s Air” or the patient “A Boy’s Day at the Fair,” offer a twinkling theme and let it sail away. This is music for the waning hour of an intimate dinner party, a kind of mental digestif after a night of heavy conversation.

Darin Gray & Loren Mazzacane Connors

This Past Spring

Compact Disc (CD)

For the last 40 years, Connors has reveled in the duo format. From his early carefree recordings with Robert Crotty through his repeated stints alongside the likes of Keiji Haino, Kath Bloom, Jim O’Rourke, and especially Alan Licht, he’s used his pairings as opportunities to find something new through his guitar. Seldom has that been more apparent than on This Past Spring, his second full-length escapade with Midwest bass mainstay Darin Gray. One of the most emotionally-fluid and musically-expansive sets in Connors’s catalogue, these seven improvisations shift seamlessly from stubborn brooding to sheer bewilderment (Parts Three through Five), from a cautious calm to a gracious sigh (Parts Six through 7.) “He knows much more about music than I do,” Connors says of Gray, agreeing that’s true of most people he joins. “That opens up some doors, even if I don’t know to what.”

Listening to This Past Spring feels like sitting in on a conversation between two old friends as they catch up on gossip, grievances, and plans. But before they convened in the auditorium of Bloomington’s Monroe County Public Library in March of 2000, Connors and Gray had played together only a few times—on an album with Licht; on their 1999 duo debut, The Lost Mariner; and occasionally live. Still, they seem to support each other’s thoughts, with Gray’s rugged bass tone buttressing Connors’s silvery licks. Gray is there to commiserate when Connors seems to growl with his guitar during “Part Five” and there again when he lets it all go in “Part Seven,” sliding toward silence.

Haunted House

Blue Ghost Blues

Despite the sense of collected drift that permeates most of Connors’s catalogue, there are unmistakable outbursts, too: discordant paroxysms that shout out what his spectral improvisations can’t sufficiently moan. That is a fitting context for Haunted House, his sporadic and short-lived blues-rock quartet with Langille, guitarist Andrew Burnes, and percussionist Neel Murgai. In the late ’90s, Haunted House didn’t play the blues so much as deconstruct them, borrowing riffs and rhythms and lyrical conceits for an anxious reappraisal of eternal human worries—loneliness, love, death. “I was in a rock band when I was 15,” Connors says. “Haunted House made me feel like a kid again. If it wasn’t fun, why bother doing it?”

Blue Ghost Blues—named for the same woebegone, Depression-era tune by Lonnie Johnson that gave Haunted House their handle—documents a brief summertime reunion in New York a decade after the band’s dissolution. Burnes and Connors are supreme sparring partners, pulling at a melodic idea until it frays into an unrecognizable form. Langille leads their 12-minute take on “Blue Ghost Blues” a little like Jandek or Keiji Haino, moaning forlorn phrases into a noisy void that swallows them. As savage as they may get, the pieces always cohere, testaments to improvisers rejuvenated by distance.

Loren Connors

Beautiful Dreamer

Vinyl

“I don’t know anything about computers,” Connors admits with a soft chuckle. “There’s some art stuff I can do with a computer, but I am clueless when it comes to making music with it.” Still, 2020’s Beautiful Dreamer represents a remarkable late-career shift for Connors. After recording two improvisations in September 2019, Connors revisited the pieces and processed them by slowing them, a first for his typically in-the-moment approach. The move buffs the attack from most of his notes and stretches already-warped chords until they hover like a kaleidoscopic halo. Though the sound of Connors’s electric guitar remains preeminent here, Beautiful Dreamer recalls the tidal wonder of Gavin Bryars or even the guitar symphonies of Glenn Branca—exquisitely yearning music, arcing into the unknown.

That elegiac sense ripples through Beautiful Dreamer, completed not long after the death of Connors’s confidant and collaborator, the downtown New York legend and writer Steve Dalachinsky. He and Connors applied similar approaches—emotional candor, improvisational impulses, constant output—to their respective modes of expression. Beautiful Dreamer is dedicated to Dalachinsky, so it is gentle but insistent, like a long hug with an old friend. The more fitting tribute, though, might be the impetus it provided for Connors to try something new. For Connors, this is a quiet revelation.