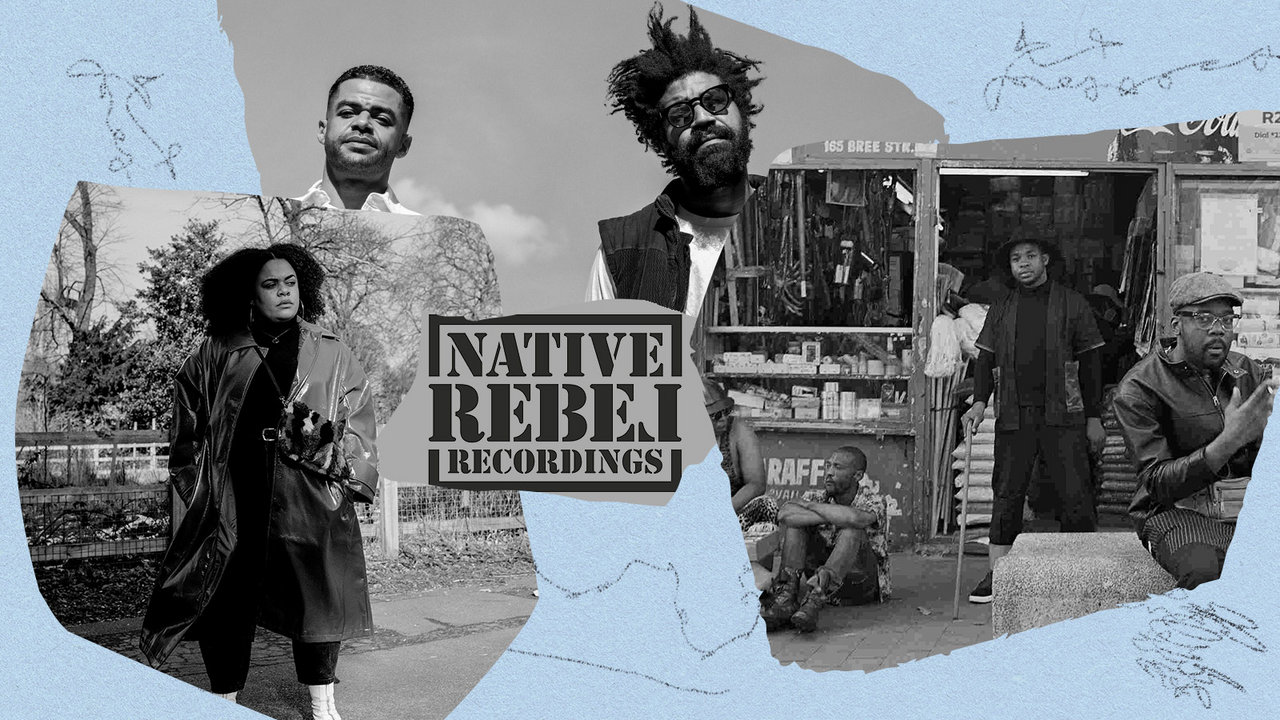

Talking to pianist, producer, and rapper Jamael Dean is like talking to a wise elder. It’s a cold, rainy Sunday, and the 21-year-old is in his apartment in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, breaking down the components of Yoruba culture. “It’s the spirit of nothing that expanded the universe into what it is now, but it’s almost like an unfathomable wisdom as well,” he says of Akamara, which, in Yoruba cosmology is the source of all existence. It’s also the basis of “Akamara,” the sprawling opening track on Black Space Tapes, Dean’s recently released debut album. It’s a slow-churning, polyrhythmic blend of spiritual jazz, full of sporadic drum fills, meditative chants, and dark piano chords. “I just wanted the band to have complete freedom to move in and out of things—almost like a standard jazz song, where you play the head-in solos or you head out. I still wanted to make it about the tradition,” he says.

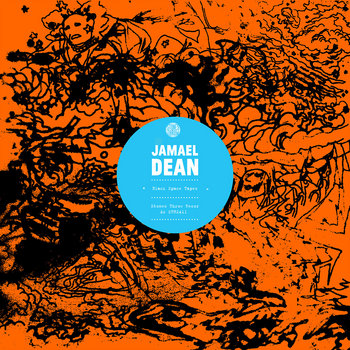

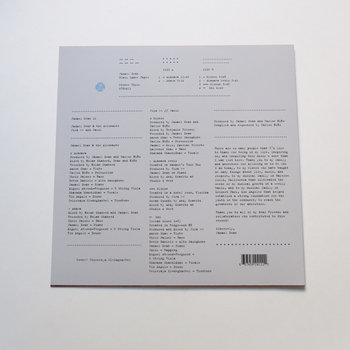

Vinyl LP

A mix of jazz, vocal and instrumental hip-hop, and neo-soul, Black Space Tapes crams a host of genres into a single, 38-minute set without ever losing focus. Occasionally, those sounds arise within the frame of one song: “Emi” begins with Dean rapping, then glides into a brief breakdown of saxophone, acoustic drums, and piano, setting up an outro of Cali-centric electronica. Dean says the idea is to show how all forms of life and music originated in Africa. On a more personal level, it highlights the music that shaped his upbringing—from his time as a child playing piano in Bakersfield, California, to a young man now studying jazz at The New School in Manhattan. Dean was given his first keyboard as a Christmas present when he was eight years old. Dean’s parents were giving him early encouragement to be a great musician—like his grandfather, Donald, a noted jazz drummer best known for his work with pianist Les McCann in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. He’d practice piano three hours a day during the school year, and six or more per day in the summer months, while all of his friends were outside enjoying the warm weather. “My dad used to be like, ‘Well, while they’re out there doing that, you’re here working on this, and it’s probably gonna pay off for you in the long run,’” Dean recalls. “He’s like, ‘There’s gonna be tons of times for you to have fun with your friends,’ which in a way made me cherish it more. It wasn’t something that happened so regularly.”

Dean has always been an old soul who idolized his grandfather and admired the camaraderie he shared with his band. “I would spend time with them at gigs and stuff,” he says. “That’s what made me want to play jazz. Because watching him interact with his buddies—that was something I could see for myself.” Dean moved to L.A. from Bakersfield when he was 14 and attended an arts high school, where he met peers who liked the same kind of music. He soon started making jazz-inflected beats in his spare time. From there, he formed a band called Jamael Dean & the Afronauts, and started performing around the city. A year later, Dean caught the attention of jazz superstar Kamasi Washington, and appeared on the song “Tiffakonkae,” from 2018’s Heaven and Earth. Then he went on the road with bassist Thundercat as part of his trio.

Vinyl LP

Composer Miguel Atwood-Ferguson first played with Dean six years ago as a member of Nedra Wheeler’s band. Soon after, Ferguson started calling the pianist to work on music and perform with him on the road, and the two formed a creative connection. “I took him to South Africa last year and we played at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival, and that was such a huge honor,” Ferguson recalls. The city was in the midst of a severe drought: “We started to play the concert, and then it started to rain. And as our set intensified, the rain intensified. When we finished our set, it stopped raining and they started calling me (in Afrikaans) The Bringer of Rain—they said, ‘Don’t stop playing.’” That was Dean’s first trip to the continent. He remembers being nervous about going there because, as an American, he didn’t know how he’d be accepted. But once he got to Cape Town, he says it felt like home. Perhaps on purpose, Dean’s music has become metaphysical—like he’s fully tapped into his heritage. “He’s really evolved a lot more,” says Ferguson, who appears on Black Space Tapes. “He kind of goes to another zone. He’s aware of what’s going on around him harmonically, but he’s completely going spiritual with it, and he’s leaving traditional harmony and going to this place where it’s almost like he’s dialoguing with some other spirit.”

Carlos Niño gave Jamael’s band their first residency at his club, The Del Monte Speakeasy in Venice, Ca., in 2016. Niño, a celebrated bandleader and producer in his own right, became an immediate fan the minute he heard Dean play. “He’s a piano prodigy,” Niño says. “He can not only play, but he’s also an incredible composer. When I think about Jamael, I think about the lineage of musicians I love, and how early in their lives they started really going for it. And he’s just one of them. He’s completely in it.” Niño co-produced, compiled, and sequenced Black Space Tapes, which he says is just a small sampling of Dean’s vast artistry. “He could’ve easily come out the gate with a triple album of music. This almost reads like a short LP, but it’s really an introduction. This is a variety of what this guy does.” If nothing else, Dean hopes the album nudges listeners to absorb Yoruba culture. “Just to research it and find out what it means for themselves,” he says. “That’s what I hope will happen with the music, too. I want them to hear how it applies to their life. Maybe it’s through a feeling they get when someone plays a certain way, but I want them to remember that and figure out why.”