Alfonso Kolb was only 18 years old when he first met Nik Alexander. It was 1978, and Kolb was a budding drummer whose only real experience playing with other musicians was in his local “rez band” on the Rincon Indian Reservation in San Diego County. At his brother’s behest, Kolb drove up to Escondido to audition for a guy who was looking for Native American drummers. That guy turned out to be Alexander, a Cree activist and musician who was heading up a new all-Native rock band called Winterhawk. “There were not a lot of Native American rock drummers,” Kolb dryly recalls. He got the job.

Compact Disc (CD)

“I had just dropped out of my senior year in high school, and my parents weren’t too happy about that,” Kolb recalls. “But I said, ‘I’ll find something, I’ll rebound.’ I didn’t realize the decision I had just made by dropping out of high school. But as luck would have it, by meeting Nik and joining Winterhawk, it took me on a whole new adventure.”

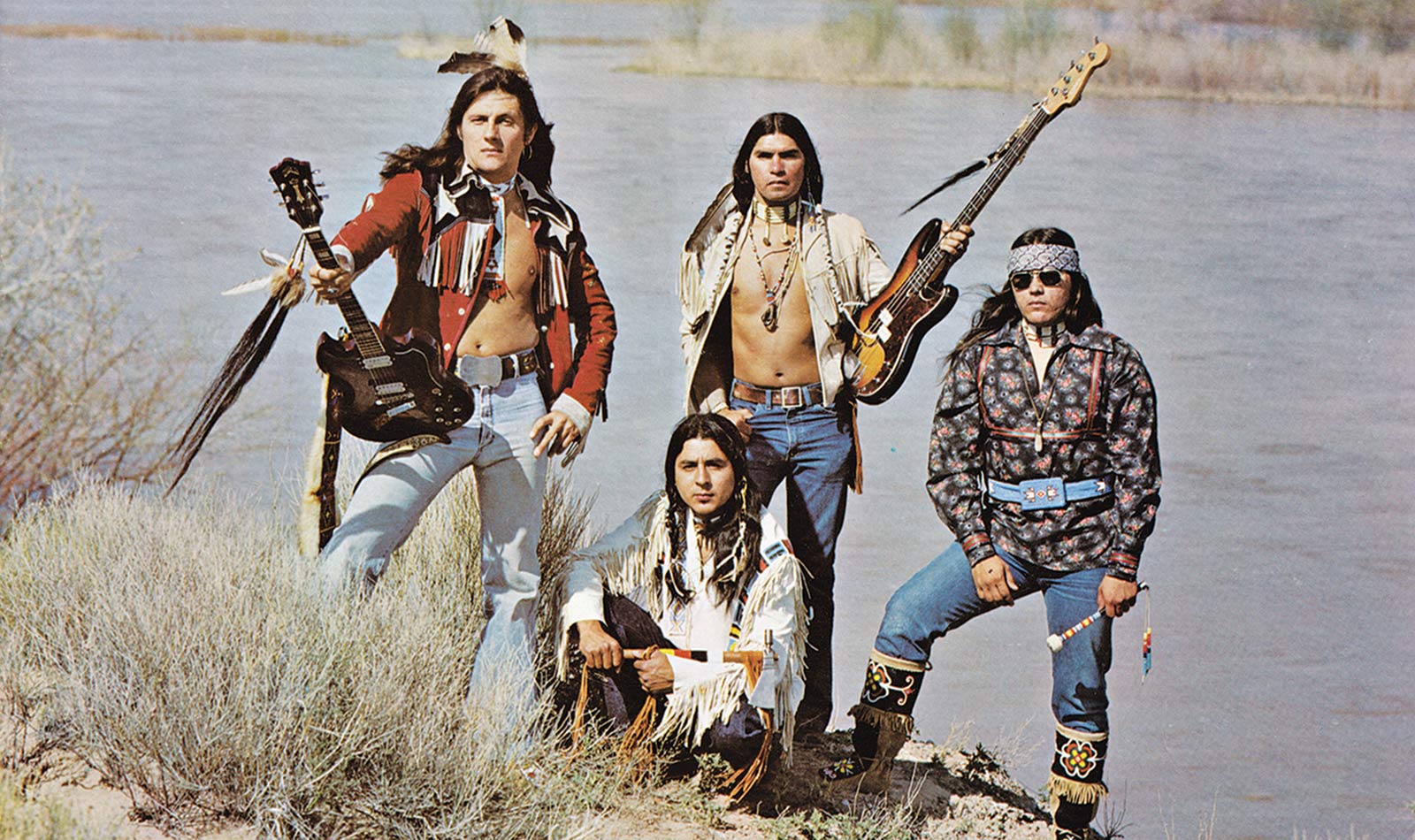

With Alexander on lead guitar and vocals, Kolb behind the kit, Frank Diaz de Leon on bass, and Kolb’s cousin, Frankie Joe, on rhythm guitar, the lineup for Winterhawk fell into place. After about a month and a half of rehearsals in Escondido, Alexander showed up to the practice space one day and told his bandmates they were going to Albuquerque to cut a record with engineer John Wagner at his studio, Mother Earth. Visions of fame swirled in Kolb’s teenage mind. “That was about the highest point in my life at that point,” he says. “All I could think of was, literally, ‘Wow, I’m gonna be a rockstar—I’m gonna be rich!’”

The Mother Earth sessions yielded Electric Warriors, a fiery slab of stridently political hard rock doubling as a mission statement for the young band. The album was the first major sign that Alexander’s ambitions for Winterhawk went far beyond writing songs and playing gigs. His lyrics were pointed rebukes of environmental destruction and the alcoholism that ravaged his community, and his bone-crunching power chords were underpinned by traditional chants and drum beats. As “Fight,” the album’s powerful closing track, wound to its conclusion, Alexander invoked the people whose influence on him loomed far larger than that of Thin Lizzy and Black Sabbath: “Crazy Horse is coming/ Sitting Bull is coming/ They are all coming/ It is a good day to die/ My people are still here and very much alive/ I have spoken.”

Electric Warriors was released in 1979 by Mother Earth’s in-house label, and while it didn’t have a massive commercial impact, it was enough to kick Winterhawk into full gear. A smattering of high-profile shows, all booked by Alexander, soon followed. That June, they crossed the border into Canada for a gig in Alberta alongside XIT, another indigenous rock band, whose frontman, Tom Bee, had helped produce Electric Warriors in Albuquerque. After a short hiatus and a second album, 1980’s Dog Soldier, the band relocated to San Francisco, where they played with acts like Johnny Winter, Y&T, and, on one memorable occasion, Metallica.

“When we were in Frisco we played with Metallica, and Metallica was nobody at the time,” Kolb recalls. “We kind of got into a little scuffle with them, because they were saying we were in the wrong dressing room, and me and Lars [Ulrich] almost got into it. They called security.”

The shows that were closest to Kolb’s heart, though, were the ones Winterhawk played at reservation schools across the American West. For Alexander, those gigs were the key to everything the band was doing. “[Nik] was very concerned about what the future held for our people, mainly our young kids,” Kolb says. “We would go to boarding schools and do seminar classes prior to the show, and we would talk to these Indian kids from all over, different tribes, and the common thread that they were going through in their life was domestic violence, alcoholism, teen pregnancies, suicide, lack of education. He would always tell me, ‘We’re here right now, and when we’re gone, what’s gonna be here tomorrow for the ones we love and respect? What are we gonna do? In what way can we have a lasting effect on them?’”

“The way we would get in the door at these boarding schools—and it would take some time for the faculty to grasp the idea—was [that] we used the tool of music, mainly heavy metal, because at the time, that was the music of choice,” Kolb continues. “Through that key, we opened the door to access the children to get them to open up to us. And [Nik] would tell me, ‘You’ve gotta be good at your stuff. You’ve gotta practice, because when we go there, they’re going to be amazed at the way you drum and the way I play guitar. That’s what’s gonna take down the walls, and they’re gonna wanna talk to us, and that’s when we’ll get to hear their problems, because no one else is listening to them.’”

By the mid-’80s, Winterhawk had fizzled out, and its members moved on to other avenues of music and activism. Kolb started playing with Jim Boyd, touring the world with the legendary Native singer-songwriter and appearing on the soundtrack to the 1998 film Smoke Signals. Alexander remained active in the Native anti-drug movement, pioneering an abstinence-through-music platform that ran parallel to Ian MacKaye’s straight-edge hardcore. Decades passed, and Winterhawk’s albums, already long out-of-print, faded into obscurity. Don Giovanni Records co-founder Joe Steinhardt found a copy of Electric Warriors in a record store sometime around 2010, and when he got it home and put it on the turntable, something about it immediately grabbed his attention.

Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Apparel

“My first thought when I find a record like Winterhawk and I can’t find anything else about it is, ‘Can I track these people down and talk to them?’,” Steinhardt says. “It’s not like, ‘Can I do a reissue?’ It’s more that I want to know everything I can about this record as I get more and more obsessed with it.”

Steinhardt eventually tracked down Kolb, and the more he learned about the Winterhawk story, the more he wanted to help put their music in front of a new generation of fans. “You have to get it out there, or else it just vanishes, and these are really important records,” he says. “They were very early in so many things both politically and musically. And at the end of the day, they’re just a tight fucking band, and they have great songs.” (For his part, Kolb was astonished to hear from a record label: “I always thought nobody noticed and we were not that important, and everything he was saying was like, ‘Wow, really?’”)

When the pandemic halted the touring and recording schedules for Don Giovanni’s active roster, Steinhardt finally had enough time to dedicate himself to the Winterhawk project. Both Electric Warriors and Dog Soldier are now receiving deluxe reissues, and Steinhardt even managed to recreate a classic Winterhawk t-shirt design from the era. The reissue campaign feels like a long-overdue reappraisal of a great band that time almost forgot. The only tragedy is that Alexander isn’t around to see it.

“The last time I talked to Nik, I was in Escondido,” Kolb remembers. “It was September 9th, my birthday, and he called me out of the blue and we talked about a reunion, coming back and maybe doing another Winterhawk album.” Alexander died of cancer in 2017, and that reunion album never came to fruition. Today, Kolb is the last surviving member of the classic Winterhawk lineup.

“I miss them,” Kolb says, choking up. “I miss them a lot, and I wish we would never get old, and we could still be rockin’ and rollin’ forever. It would have been nice to have people see Winterhawk live and hear the energy and the sound. It would have been so cool. But things are what they are.”

A phrase that comes up again and again in conversation with both Kolb and Steinhardt is “ahead of their time.” Winterhawk infused heavy metal with Native sounds, wrote lyrics that excoriated the white man, and wore traditional garb on their record covers. Their very existence in the late 1970s was a provocation. In retrospect, that just makes Electric Warriors and Dog Soldier even cooler.

“I think that at that time when Winterhawk came out, society wasn’t ready for us,” Kolb says. “We had our shots, but I just don’t think they were ready for a Native American-looking band to sound the way that we sounded.”