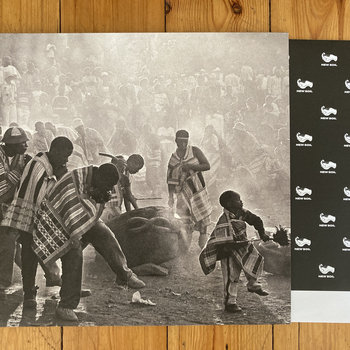

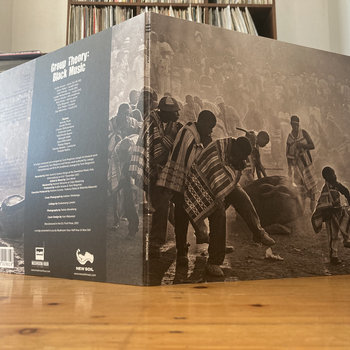

The chorale jazz canon is slender but profound. With roots that stretch toward diametrically opposed origins—Sunday morning’s church and Saturday night’s jazz club—it’s a heady blend of gospel choir exuberance atop a hard bop backdrop that makes for a formidable combination. Early ‘60s fusions like Max Roach’s It’s Time, Mary Lou Williams’s Black Christ of the Andes, and Donald Byrd’s A New Perspective were audacious, hummable, and thrilling, finding common ground in the Black musical vernacular while also soaring to thrilling new worlds. Other albums, like Andrew Hill’s Lift Every Voice and Billy Harper’s Capra Black, furthered the chorale jazz sound before other jazz hybrids—not to mention the economic strains of funding a full band and choir—pushed the style to the side.

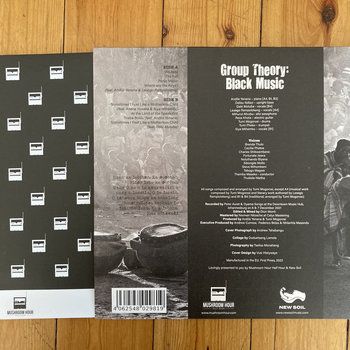

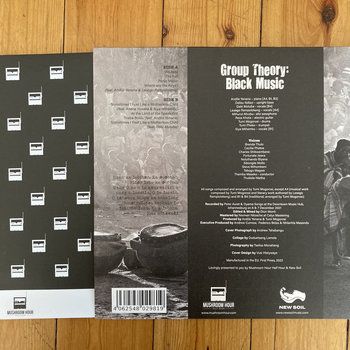

Vinyl LP

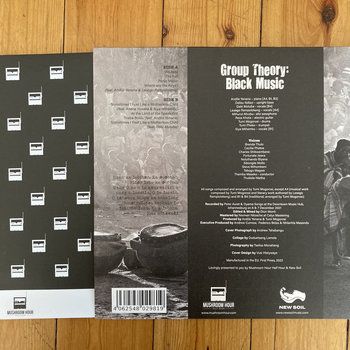

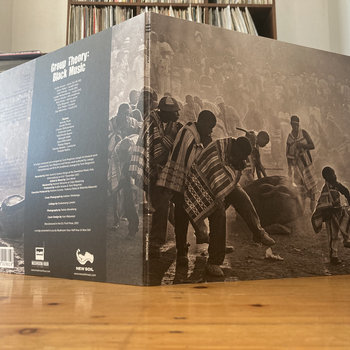

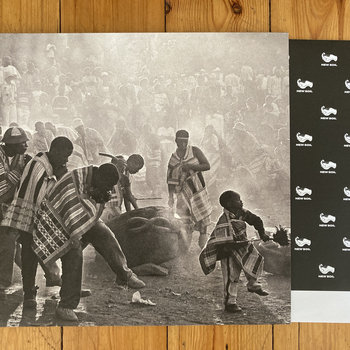

This year though, you could hear aspects of chorale jazz emerging once more. There were strains of it in the most recent SAULT album, in Kendrick’s recent work with Duval Timothy, and—most pronounced—on Tumi Mogorosi’s recent release, Group Theory: Black Music. The South African percussionist/composer came by the sound organically, tapping into the vital history of the country’s chorale music tradition. “While I didn’t grow up in church choir, my first interaction with mass music was through a brass ensemble,” he says via video call from his living room in Johannesburg, speaking over the purr of a power generator amid his city’s rolling power cuts. “Opposite my grandmother’s house was this church with a brass ensemble, and my first interaction with the music was through the choir in high school.”

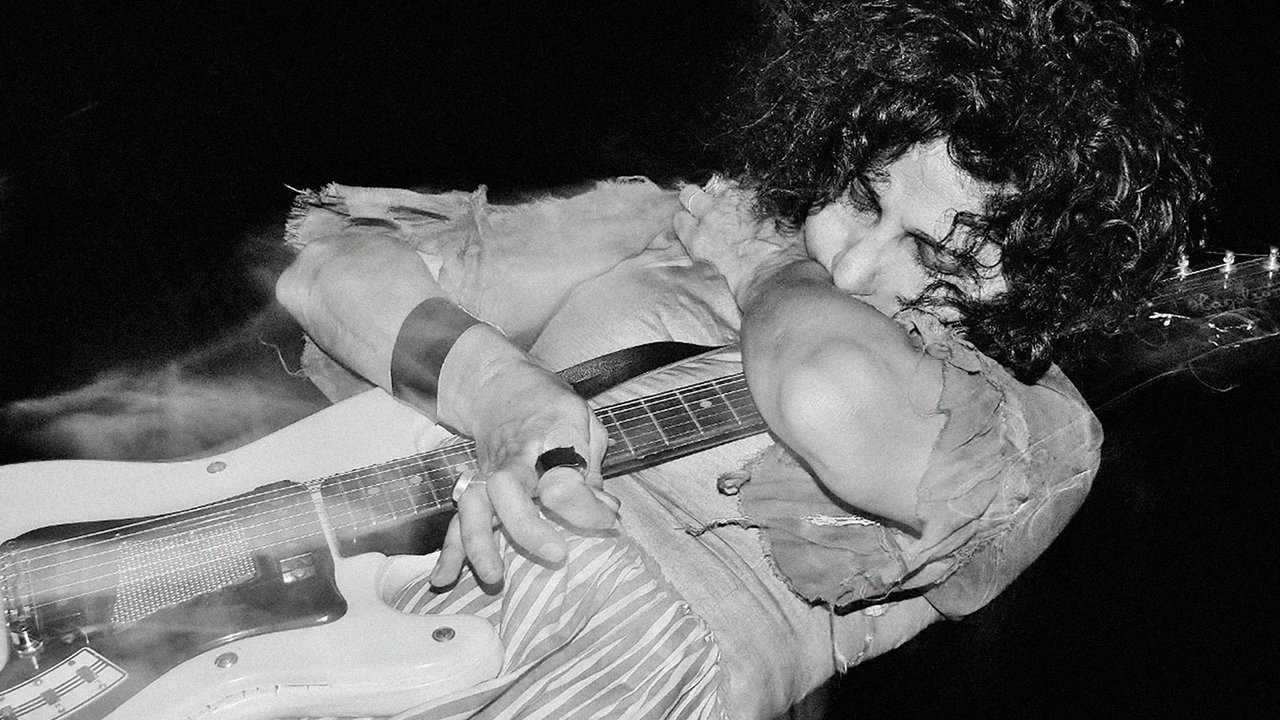

Mogorosi was first drawn to the guitar, looking up to the likes of Wes Montgomery and Joe Pass, and soon he was playing gigs throughout his time in college. But as graduation approached, there was a sea change within him. “I don’t really have a coherent answer for why I switched to drums; it just happened,” he says. “When I got my degree, I officially stopped playing the guitar and gave away all my guitars—even a Gibson 1976 model that I gave to my cousin, who then took it to the pawn shop.”

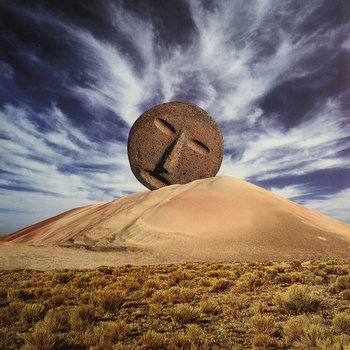

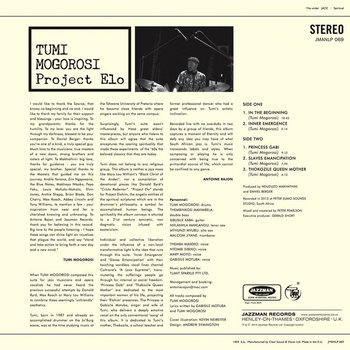

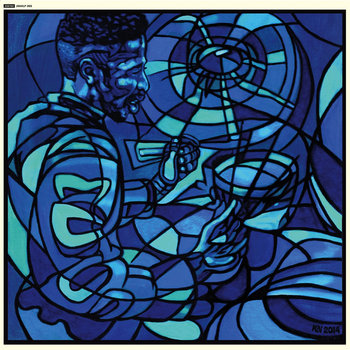

After giving away all his guitar gear, Mogorosi had no other option but to double down on the drums. “There was no way of me going back, so I made a conscious choice,” he says. “I wanted to put in the required hours for the drums.” Within a few years, he was fully booked on the Johannesburg jazz scene behind the kit. And in 2014, he released his debut album as leader, Project ELO.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

That album featured Mogorosi helming a sextet, bolstered by four vocalists, drawing on the South African choral tradition without much knowledge of its small but potent catalog in modern jazz aside from the Roach and Byrd albums. “It was not a conscious connection,” Mogorosi says. “Only after Project ELO, did I do the digging.” He also began to play in different groups, from the avant-garde-inflected trio The Wretched to his ongoing dialogue with British-Barbadian saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings in the expansive South African group Shabaka and the Ancestors.

Even with two critically-acclaimed albums that brought world notice to the tireless work of Hutchings and to the vibrant jazz scene in Johannesburg, Mogorosi felt there was more to be said. “Elo always felt like an unfinished project,” he says. “In my subconscious mind, I always wanted to finish up that project, so maybe Group Theory: Black Music is part of that.” But the early part of the pandemic made getting a large group—plus an additional ten singers—together almost impossible.

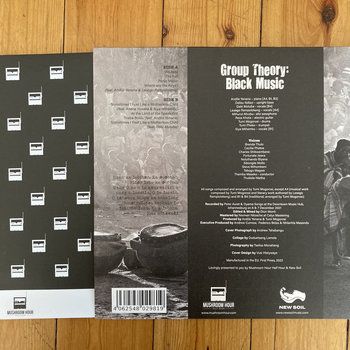

Mogorosi continued to hone his vision, always with the thought of these voices at the forefront, yet with his role as the drummer and their role inverted. “The voice has always been this thing that can propel the energy of the band and keep it there, without needing to release the tension,” he explained. “It can keep the tension there without it feeling uncomfortable. The drums can then create that thunderous backdrop around that intense center.” On a number like “The Fall,” the wordless voices sustain the band as Mogorosi’s snare and cymbals and Reza Khota’s swirling guitar lines spiral around the group. On “Walk With Me,” Mthunzi Mvubu’s saxophone and Khota’s guitar tease out timbral colors from the group of voices.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

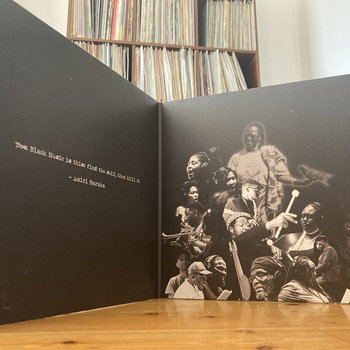

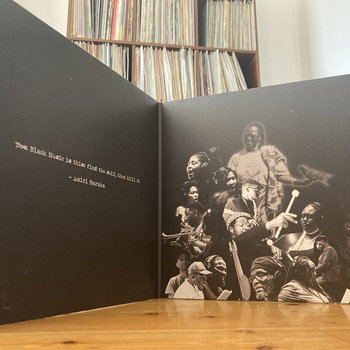

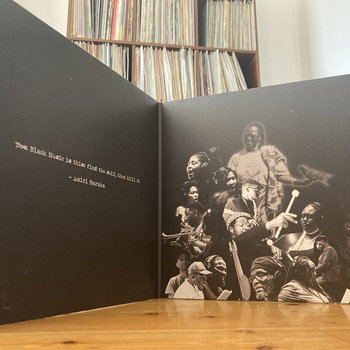

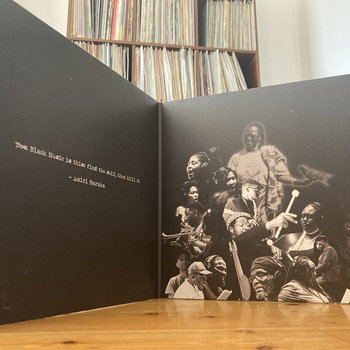

Through most of the album, these massed voices remain abstracted and wordless, accentuating and heightening the drama of songs like “Panic Manic” and “At the Limit of the Speakable” with “ooh”’s and “aah”’s. “I was thinking more in terms of creating a soundscape that deals with certain notions of the unconscious and how to bring people into this space of the Black Unconscious,” Mogorosi says. “I’m trying to map these moments of a feeling of precarity, a feeling of uncertainty of futures of what it means to be Black in the world.”

The album climaxes with not one, but two iterations of the Negro spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” a song whose origins stretch beyond historical documentation. Its ache and primordial sense of estrangement arose from the days of slavery in the United States, but we might never know who first distilled such sorrow into verse. Its first entry into the historical record comes in 1870, when the legendary Fisk Jubilee Singers began to perform it across the United States. In 1918, composer H.T. Burleigh set it down in sheet music, and Paul Robeson recorded an early version in 1926. Since then, its sentiment has since echoed through the greats: Mahalia Jackson, Harry Belafonte, even Prince.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“There are certain landmark songs that speak about displacement and dislocation, and ‘Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child’ is one of these canonical songs, a Negro spiritual that speaks about the spiritual yet also the socio-political displacement, taking into account the incapacity for one to explain to explain what that means,” Mogorosi says. In one version, the aching lyrics are delivered by singer Siya Mthembu; in the other, by Gabi Motuba, who worked with Mogorosi on his first album and as part of his other group, the Wretched. Her version offers a glint of hope, reiterating a line about “we come a long way from home” as Khota’s poignant guitar winds around her voice, Mogorosi’s understated snares and brushed cymbals buoying the otherwise heavy burden of the song.

“These feelings are at the level of the preconscious mind, and the song brings these moments of anxiety and the nervous condition up,” he says. “For me, it was important that both Black male and Black female sing it as a way to complete the narrative. The narrative becomes one-sided if only Siya or Gabi sing it. I arranged it differently for both, to have it feel the same, but different. The story becomes complete with both of them partaking.” Despite not all being in the same room for years, Mogorosi was struck by how the album cohered: “It all happened so quick, I was amazed. It was also seeing friends for the first time in so long. Everyone was eager to play the music and experience it.” And with that, Group Theory: Black Music enters into the chorale jazz canon and stands as a poignant high point in the recent South African jazz renaissance.