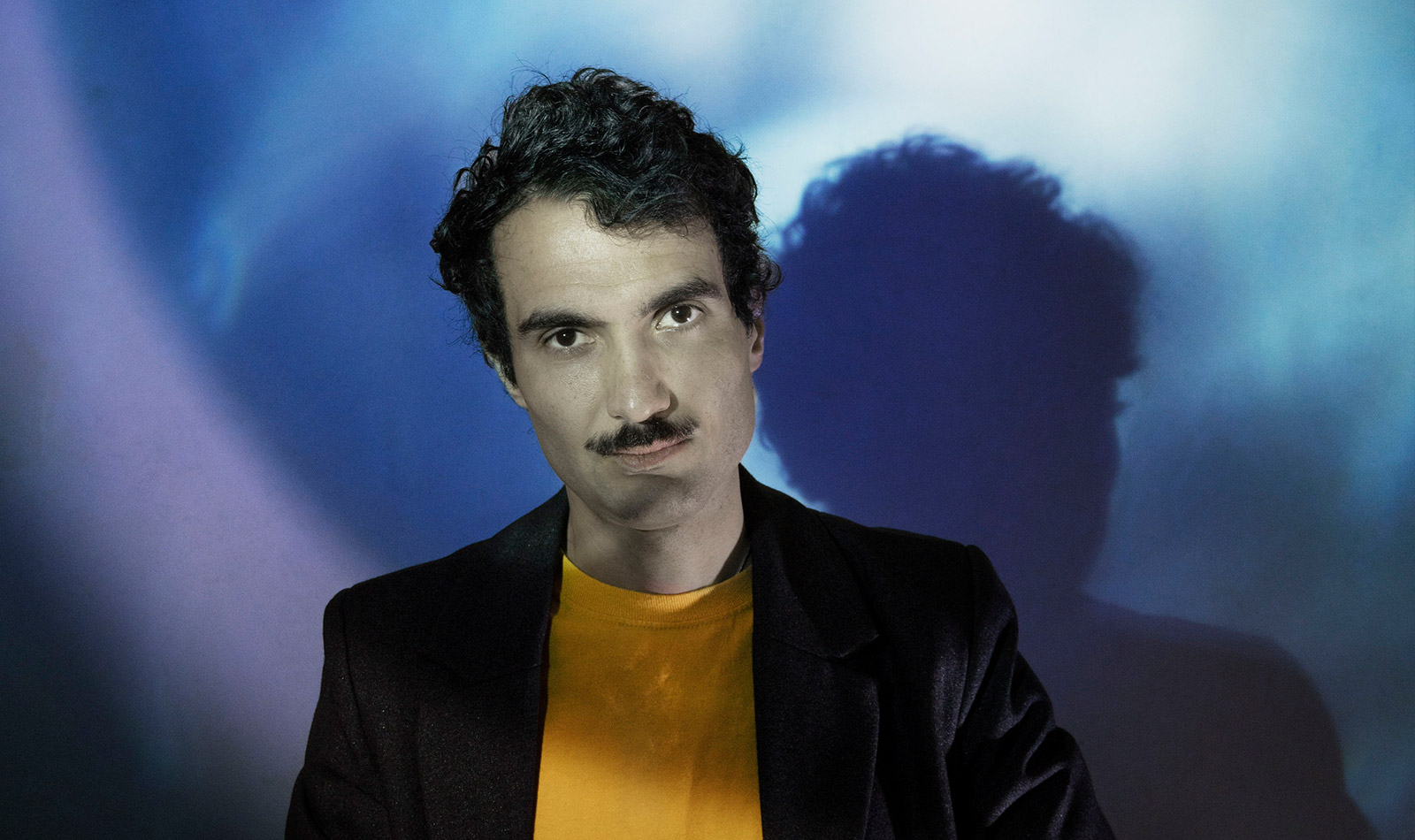

Tigran Hamasyan calls in, rather unexpectedly, from Venice. After stints in New York, Los Angeles, and Armenia’s capital Yeravan, he’s been in the tourist-free surroundings of Venice for six months now, a period of relative stasis in a life punctuated by regular changes of scenery. “There was a point around 2015 where traveling just got too much for me,” he says. “At 110 concerts a year, I wanted a break—anything you do too much of, you’re gonna hurt yourself at some point, you know?”

A sense of constant movement characterizes Hamasyan’s varied discography, usually straying far from established pathways. Following the prog-metal onslaught of The Call Within with StandArt, his first album of standards, is exactly the sort of gear-change listeners have come to expect from the Armenian-American pianist, who has worked across rock, folk, choral, film, and chamber jazz projects since recording his debut album, World Passion, in 2005.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

But, as the trio crashes through Elmo Hope’s “De-Dah,” here transformed into an angular puzzle of dark harmonies and shuddering grooves, there’s a sense of familiarity in Hamasyan’s distinctive style. “The idea was to take liberties with these melodies. The same kind of liberties I take with, let’s say, Armenian folk music, or melodies I write. It’s just as if I wrote the melody,” he says. At times, Hamasyan sounds like he’s approached the music from the outside in, such is the degree of abstraction that well-known tunes like “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” or “All The Things You Are” are subject to.

Hamasyan regularly references his native Armenia. 2018’s For Gyumri is named after the mountainous city he grew up in, and the myths and legends of the region—Ara the Handsome, Mount Aragats—appear regularly. On StandArt, though, the source material is different. Does he view these jazz standards in a similar way, as folk songs born of an American folk tradition? “American, and also kind of world,” he says. “I feel I belong to a very small community of jazz lovers around the world. [The standards are like] a group of international jazz-folk songs. But the bottom line is, I just love those melodies.” That’s just as well, as fragments of melody are about the only thing that remains intact as Hamasyan, bassist Matt Brewer and drummer Justin Brown exhaustively dismantle the originals.

In truth, “StandArt” had no real great conceptual drive, no reverential itch that needed scratching. Hamasyan says he finally had time to “dive into this material and build a repertoire” during lockdown. It features a lot of jazz’s big hitters—Joshua Redman on Charlie Parker’s “Big Foot,” Mark Turner on “All The Things You Are,” Ambrose Akinmusire on “I Should Care”—all similarly grounded during the pandemic.

But StandArt did provide Hamasyan with the chance to reflect on his family’s relationship with America. “My father became an illegal immigrant; when I was 12, he went to the U.S.A. and stayed there to get the papers so that we could move to the U.S., to make sure his kids have a better future.” The family moved from Armenia to Glendale, California, a city possessing a large Armenian community that already included Hamasyan’s uncle. “We got used to the whole family living in a studio for two months. It was the classic story of becoming an immigrant.”

The teenage Hamasyan found the U.S. a bit of a culture shock; though scattered with depressing moments, musical life moved extremely quickly for him. Eight months after immigrating, he recorded his first album, with Ari Hoenig, Francois Moutin, and Ben Wendel. Hoenig and Moutin also provided a life-changing experience for a young Hamasyan; the two musicians were famously part of the Jean-Michel Pilc Trio in the ‘90s and ‘00s. “I hadn’t heard anything like that before, as far as rhythmically what you could do with standards.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

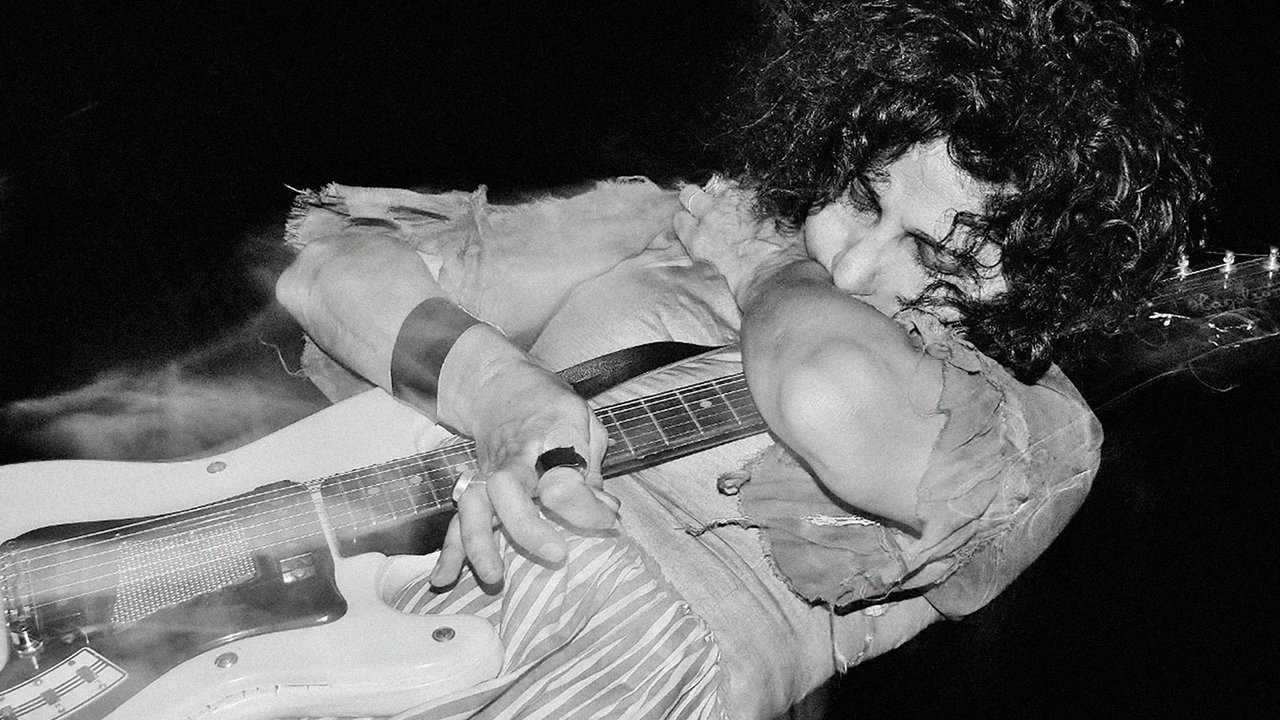

Hamasyan’s unpredictable beats are the most striking aspect of his music—both the warring polyrhythms (he speaks of playing fives over elevens over a regular four-beat groove as a practice routine) and the frequent feel shifts, from mechanical flurries of semiquavers to phrases that sit way behind the beat. “It becomes such a part of your musical language that you breathe odd meters,” he says with a smile.

There’s an intense energy to his work, too, that exceeds musical construction. Where might that come from? “Honestly, I was like that since I was a kid. I just had really energetic personality,” he says. “When I was a kid, I used to love the old karate movies—Bruce Lee or Jean-Claude Van Damme. Bloodsport is probably one of my favorites.”

Hamasyan has traded action for a slower pace of life in Venice. “You can run or walk everywhere. During a day I end up walking like eight kilometers,” he says. As well as being a family-friendly space in the off-season, it’s also an opportunity to keep his head down and do what he likes best—practicing his instrument. “I feel sometimes people lack that, because there’s so much information coming at you, it’s hard to filter things out, and never really immersing and going in one direction.” For Hamasyan’s listeners, that direction is certainly singular, if unpredictable.