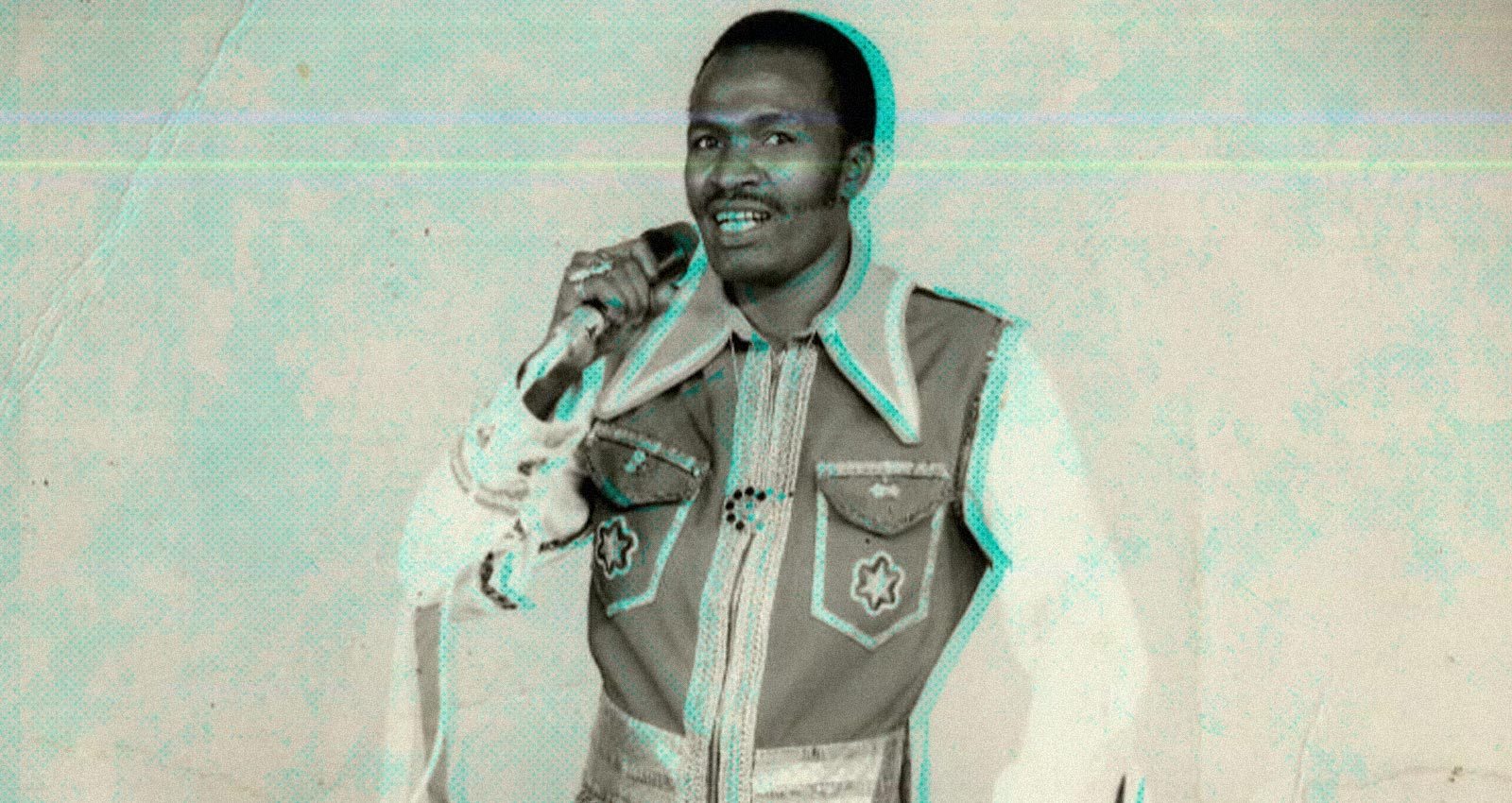

Joseph Kamaru was only a teenager when he moved to Nairobi from rural Kenya in the late 1950’s, with a dream of one day becoming a musician. A quickly evolving city still a decade away from independence, Nairobi attracted musicians from all over East and Central Africa, and the sounds of Benga, jazz, Congolese Soukous, and Gospel could be heard blasting out from clubs and open windows.

Kamaru made money working as a street-hawker, a house-help, and a fruit seller, saving enough money to buy his first guitar. Within a few years, he’d added the accordion, keyboard, and traditional karing’aring’a and wandindi instruments to his repertoire. By 1965, two years after obtaining freedom from Britain’s colonial rule, Nairobi had become the region’s musical hub, home to countless independent music labels, recording studios, and even the region’s first legal vinyl pressing plant. Competition was tough, but Kamaru’s unique sound, which merged traditional Kikuyu melodies with the distinctive bass guitar riffs and high-pitched vocals of benga, quickly became popular among the city’s revelers.

Amid Kenya’s optimistic yet complex post-colonial years, it was Kamaru’s sobering themes that set him apart. Expressing himself through ambiguous metaphors and Kikuyu proverbs, the young musician sang about sexual harassment, morality, love, and—most strikingly—about politics. Over the next four decades, Kamaru would aim both high praise and bitter criticism at the country’s ruling elite, a habit that resulted in him falling in and out of favor with different Kenyan presidents; Kamaru was both a powerful ally and an enemy to be feared.

“He grew up during the Mau Mau rebellion [the uprising against British colonial oppression], so with so much political stuff happening, it really affected how he wrote his songs,” says Kamaru’s grandson, himself a successful producer and field and sound artist who goes by the name KMRU. After his grandfather’s death in 2018, it was KMRU who decided to reissue his work via Bandcamp, with the aim of using the profits to one day repress the music on vinyl.

Kamaru’s songs often touched upon issues that were considered taboo at the time, treating them with surprising sensibility and nuance. In “Tiga Kuhenia Igoti (Don’t lie to the court),” he tells the story of a young woman who bravely faces her attacker in court: “When we got to your house you tricked me and told me you’ll take me to work tomorrow / At 9pm, I won’t be shamed by men to say that you touched and strangled me,” sings Kamaru, duetting with his sister Catherine. “Lets stop lying to the court, Young man.”

“Having been raised under colonialism and experiencing all those struggles, he felt that it was right for him to use his music to tell stories that really connected with people,” says KMRU.

He once caused outrage with his song “Ndari Ya Mwarimu,” in which he plays the part of a young student who rebukes the advances of a male teacher. In the song, the girl criticizes the Kenyan education system, saying it tolerates sexual harassment, and demands that the teacher be tried by a court of elders. Kenya’s teacher’s union was so enraged by Kamaru’s lyrics that they threatened a nationwide strike, forcing parliament to debate the issue, and President Jomo Kenyatta to intervene and calm the situation.

Kenyatta, who ruled Kenya from independence in 1963 until his death in 1978, understood that having Kamaru in his corner was a powerful asset. But while the musician was happy to lend his support, he wasn’t willing to compromise his principles. “During political campaigns, politicians wanted him to write songs for them,” says KMRU. “He had close relationships with them, but he would also sometimes turn against them.”

By 1969, Kamaru’s musical career was in full swing, but the country around him was in chaos. The country was preparing to hold its first general elections since declaring independence in 1963, but Kenya People’s Union—the only opposition party—was banned, and its leaders arrested. Ethnic tensions flared, and the shooting of popular politician and independence activist Tom Mboya—widely believed to be a politically-motivated assassination—sparked rioting across the country. Kamaru stood by the president, praising him and vehemently criticizing his detractors in the song “Arooma Ka.”

That all changed in 1975, when the body of former Mau Mau fighter and popular politician J.M. Kariuki, was found on top of an anthill in Nairobi’s Ngong Forest, where it’d been burned and brutally discarded. All fingers pointed to Kenyatta’s government: after all, Kariuki had rallied against corruption and criticized the elites in a time when dissent was not tolerated. Despite his close friendship with the president, though, Kamaru refused to stay silent. That same year, he responded with “J.M. Kariuki,” a protest song demanding answers from the government and wishing terrible fate upon the murderers. The incendiary track ended up being an unprecedented hit, selling 75,000 copies within the first week.

“During that time that he had this red beat-up car,” says KMRU, “and lots of people knew it was his car, so he had to hide it, because the government was after him.”

When Kenyatta died in 1978, his successor Daniel arap Moi realized that it was better to have Kamaru as an ally than an enemy, so he invited him on a presidential visit to Japan. The musician wrote “Safari ya Japan (a trip to Japan),” in praise of the president, and would pen several other compositions in his honor.

But like Kenyatta before him, it wasn’t long before Moi learned that Kamaru was as quick to condemn as a he was to offer praise. In 1983, when President Moi launched increasingly repressive measures in an attempt to consolidate his power, Kamaru used ambiguous language and Kikuyu idioms to send the president a warning: “If the bees come out of the hive / Somebody will get stung,” he sang on “Ni Maitho Tunite.”

Kamaru kept churning out songs that demanded justice and fairness, whether in politics or personal relationships, until he converted to Christianity in the 1990’s and swapped political songs for gospel. Still, his influence never dimmed, and politicians were keen to keep him on their side right up until the day he died.

“In his last days, he used to come to my mum’s house and talk to me a lot about music, about life,” says KMRU. Kamaru was proud of his grandson for choosing to pursue music, and for making something so unique. Sound-wise, there is little of Kamaru’s Kikuyu benga in KMRU’s experimental electronica, but his impact has arguably been even deeper: “He told me to stay authentic with the music I do, to stay honest with myself,” KMRU says. “And that’s what helped me, in certain moments, to choose my own path.”