The South African poet laureate Keorapetse “Willie” Kgositsile once wrote these words: “This wind you hear is the birth of memory. When the moment hatches in time’s womb, there will be no art talk. The only poem you will hear will be the spear point pivoted in the punctured marrow of the villain, the timeless native son dancing like crazy to the retrieved rhythms of desire fading into memory.”

Kgositsile died on January 3 of this year, and it’s hard not to see his passing in the lineage of other great black poets recently lost, like Gil Scott-Heron in 2011, Amiri Baraka in 2014, and Maya Angelou later that same year. In that regard, the name of the legendary ‘60s group The Last Poets—which was inspired by Kgositsile’s poem—feels uncomfortably real.

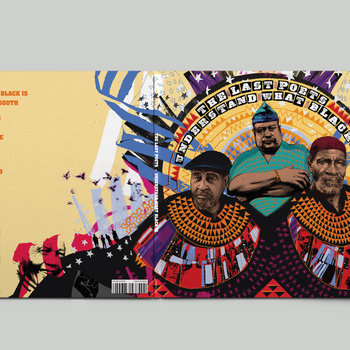

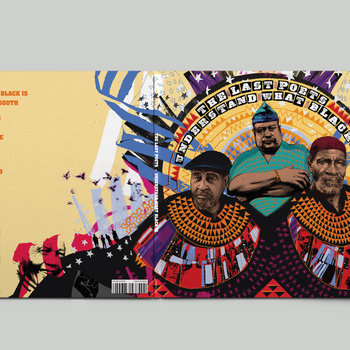

But some 50 years since their initial formation, The Last Poets are still a vital, necessary force. Their new album Understand What Black Is—their first in 20 years—arrives into a world that’s capable of being just as distressing as it was when they first began recording.

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The Last Poets’ first performance was on May 19, 1968—the birthday of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, aka Malcolm X—at what was then Mount Morris Park in Manhattan’s Harlem neighborhood. Now known as Marcus Garvey Park, the area just a short walk away from a new Whole Foods Market, the arrival of which has been hotly contested and debated. The Last Poets founding member Abiodun Oyewole recalls his home—Black Harlem, he says—in its prime. He remembers its enchanting nature and the deep sense of history that’s still there. Oyewole knew Miles Davis and Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael), saw Malcolm X as a child, and remembers the impact of Amiri Baraka’s work firsthand. “I knew him before he was Amiri Baraka, he was Leroi Jones. He, in fact, is one of our mentors,” Oyewole reflects. He came up with the likes of Sonia Sanchez, Alice Coltrane, Nina Simone, and Sun Ra.

In ‘68, a couple of months before Martin Luther King’s assassination, Howard students led a legendary occupation protest against the Howard administration and won their demands. Fifty years later in 2018, Howard’s students were forced to do it all over again, and they won again. Back then they were chanting “Are you ready ni**er,” which inspired The Last Poets early on; this time they were chanting Rihanna’s lyric “Bitch better have my money.” Here, the connectivity of time suggests more than just repetition, it tells us how the past can show us the details of transformation to help us form an agenda for this time.

In the rapidly changing neighborhood, where gentrification forces residents to leave communities where they’ve established roots, a song like “Understand What Black Is” rings true. Its lyrics implore the listener to understand the beauty of blackness. “Black is humanity,” Oyewole says in the song, declaring both a universal truth and setting the tone for the rest of the album.

The Last Poets have kept busy despite their two-decade hiatus. “We have been traveling all over the country performing,” Oyewole says. “It’s been very exciting. The main thing I’m doing is just keeping my writing alive.” Umar Bin Hassan, who is currently based in Baltimore, made it clear that, despite the group’s absence from the studio, they have always remained together. That camaraderie can be heard throughout the new record. The poetry is calm and patient, with a lyricism that’s not far off from what you’d hear from elders in the black community—there are moments on the album that feel like you’re listening to black fathers, uncles, and grandfathers recite poetry. The songs celebrate black power and lament the persistence of oppression.

Sonically, the album is something of a departure from the band’s previous work, pulling in influences from reggae, ska, and dub. The album was produced by Ben Lamdin of Nostalgia 77 and Brighton’s Prince Fatty, who works in traditional reggae and dub; it’s easy to detect the influence of artists like Black Uhuru, King Tubby, Scientist, and Keith Hudson throughout the album. “We’ve had hip-hop behind us, jazz, and the blues, but that reggae, though,” Bin Hassan says, “that reggae just seemed to open up our words.” Percussionist Baba Donn Babatunde described the new sound as a mystical channel to give out the message and the word to people who would identify with it all over the world.

Some tracks stand out lyrically because their interesting concepts draw a direct line to their evolution as a group. “How Many Bullets” expresses how rebellion against oppression creates an immortality for those whose legacy will surpass mortal limitations. “We live in awe of ourselves / You can’t kill me / You can’t kill what you can’t see,” Oyewole says, sounding unfazed by the thought of death. Other tracks, like “Certain Images” and “Rain Of Terror,” find the group returning musically to jazz, and teasing other free form musical elements like the percussion that has long defined their sound. Most, if not all, of the tracks feel like declarations, statements, and intentional expressions of the group’s legacy. On “What I Want To See,” Oyewole imagines a better world, despite existing in one that often seems to repeat many of the problems he’s long fought.

Now, some 50 years later, the Last Poets have seen poetry and black culture evolve tremendously. They’ve also been a large part of the narrative, even if they never quite made it to the mainstream. “Dignity, pride, integrity, understanding, and the understanding of what is to be a human being,” Bin Hassan says of the group’s legacy. “I see myself not as a star,” Oyewole continued, “but a rock up in the sky who people have polished to shine to look like a star.

“As Black people, nobody can touch us,” Oyewole concludes. “Music has been our salvation. We are music and we have created all kinds of music just to survive in this land.”