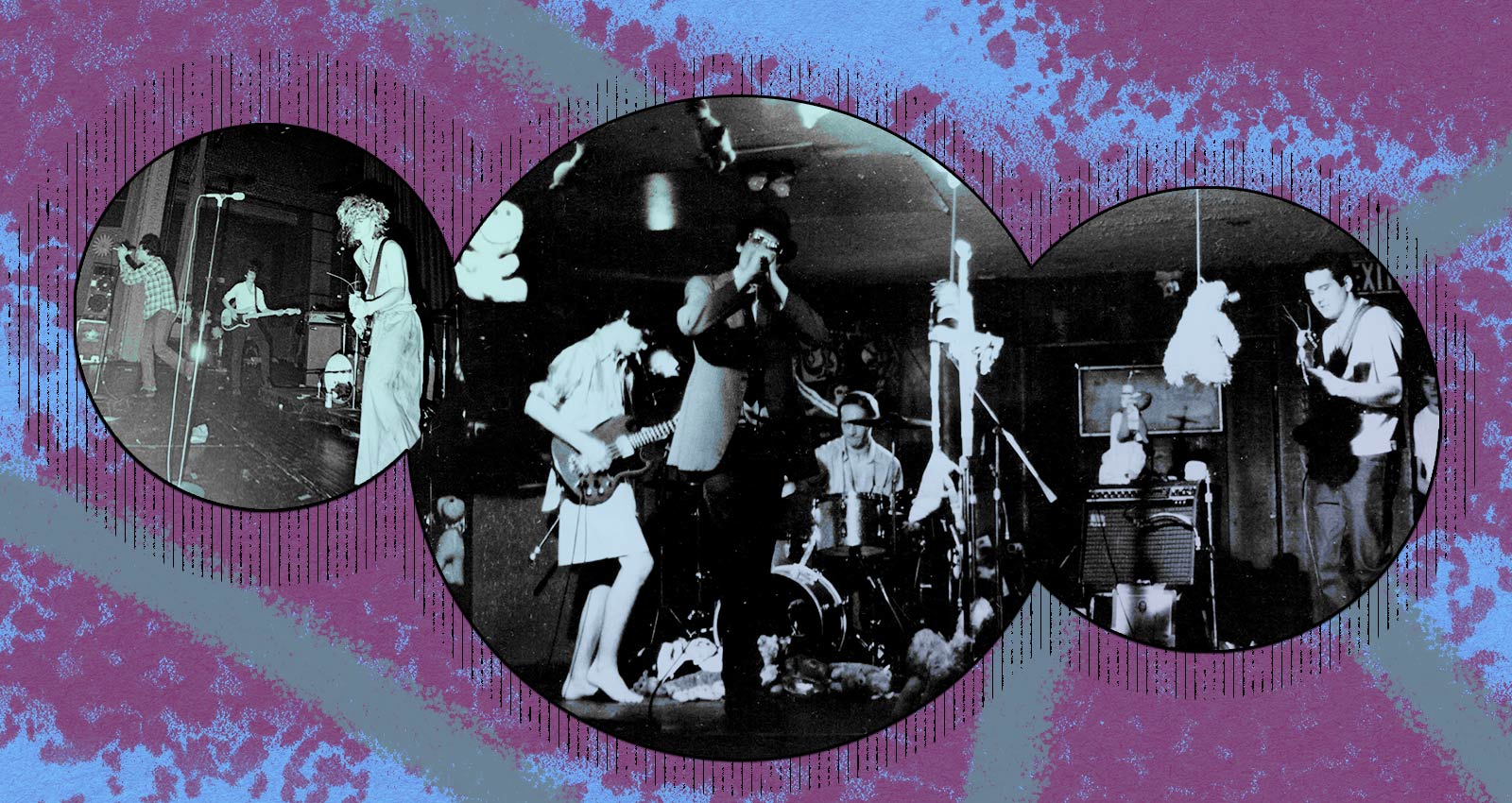

Released to modest national acclaim in 1984, Spike in Vain’s Disease Is Relative is one of history’s most electrifying slabs of hardcore. That’s probably because it barely qualifies as such: a whirl of dissonance and grim obsessions, the LP seldom conforms to punk-rock orthodoxy. The guitars shriek with no-wave ugliness, the rhythms pirouette as often as they thrash, and the lyrics encompass philosophical musings (“in the end we’re the victims of our waste”) and feverish surrealism (“after Attila the Hun it’s hell”). Frantic tempos and caustic shouts notwithstanding, these dudes got their kicks from Brian Eno, the Gun Club, and King Crimson—snarling at the Midwestern cultural landscape all the while, like genre-disrupting archfiends.

Vinyl LP, , T-Shirt/Apparel

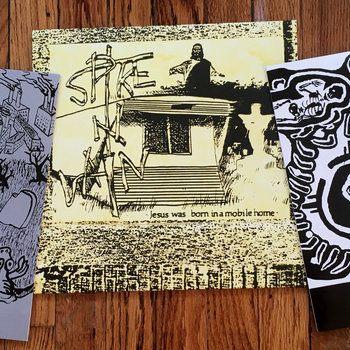

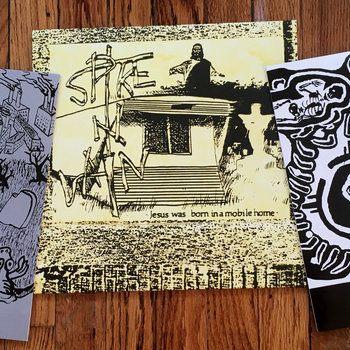

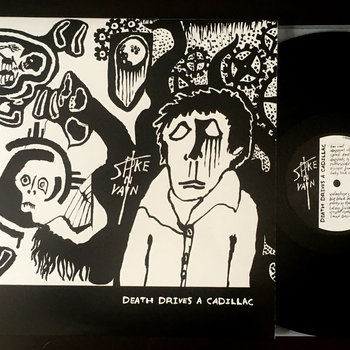

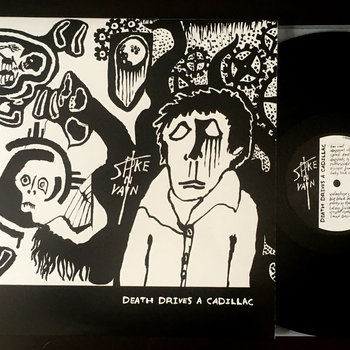

Over the decades, the album has matured from a bargain-bin staple into a collector’s Holy Grail. Rare copies of the original vinyl now fetch upwards of $200. Thankfully, there’s no longer a reason to keep splurging. On April 30, Scat Records—the indie label that catapulted Guided by Voices to mid-’90s success—reissued Disease Is Relative, along with its aborted follow-up, the Americana-influenced Death Drives a Cadillac. During his late teens, the record company’s founder, Robert Griffin, served as one of the instrument-swapping group’s three rotating guitarists, bassists, and vocalists, alongside brothers Chris and Andrew Marec; prog-steeped drummer Bruce Allen and his replacement, Scott Pickering, rounded out the lineup.

Spike in Vain assembled circa 1982, in the model Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, Ohio. Despite that pleasant, leafy setting, the band were united by darker inclinations. “An appreciation for decay was something we talked about,” Griffin says. “To this day, I don’t feel right about a song if it’s not broken in some way.”

The music’s anxious intensity stemmed in part from Chris Marec’s introverted nature. “There was a fundamental disconnect between him and the world,” Griffin recalls. “I remember going to Andrew’s after school, before I joined the band, and Chris was sitting on the backyard sidewalk, smoking and staring at ants. I said something, but he didn’t even look up. It was a couple more weeks before Chris actually said hello. Sometimes he’d pace around the house for an hour or two, his spider-like fingers twirling in his hair.

“In all of his work, there is a sense of questioning reality and other worlds,” Griffin continues. “As far as his guitar playing, I used to just watch the crazy shapes his fingers made—and freak.”

The confident Griffin (whose itinerant boyhood included lucid dreaming, “an odd comfort about death and dying,” and a troubled mother) bolstered the Marecs’ esoteric proclivities. “I was drawn to mysterious, macabre things,” he says. “In music, that meant minor keys or crazy guitars. Between punk and hormones, my anger came out in many forms, and if I experienced any limitations on my freedom or felt helpless, it would turn inward, and thoughts of suicide would follow. I had endless vengeful fantasies of my own funeral. But I left home on my 17th birthday, felt more control over my life, and those feelings began to dissipate.”

Vinyl LP

These emotions char Disease Is Relative tracks such as the terrifying “Children in the Subway” and the swaggering “God on Drugs.” Of the latter, Griffin comments, “Sometimes we’d go at night to Lake View [Cemetery] and party until the caretakers got wise. Andrew decided we should adopt [a pair of graves], because who else was keeping them company? He imagined a government PSA campaign: Adopt a Dead Person Today. It was the kind of absurdist, morbid humor we all thrived on. Once, we brought the Ouija board along and asked what life after death was like, and the first few lines of ‘God on Drugs’ were dictated.”

For 1985’s polished Death Drives a Cadillac, a wealth of rootsier sounds crept in. “My mom grew up in small-town Ohio and Georgia,” Griffin says. “I hated country and folk music when I was young, but began to reconsider that after I revisited [Marty Robbins’s] Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. It was all about death. Both Chris and I were listening to Big Bill Broonzy, Robert Johnson, John Lee Hooker, and digging the inherent American weirdness and suggestions of supernatural realms.”

Triumphs abound, although several tunes suffer from overreach. “We weren’t a mature band,” admits Griffin, “and we were way too enamored of any new accomplishment.” Unfortunately, due to lack of funds, the project was shelved and Spike in Vain dissolved that December. Griffin and Pickering formed the boisterous Prisonshake, and the Marecs resurfaced in the sparsely documented Soul Vandals. The brothers would only survive until their early fifties: Chris died in 2013, Andrew in 2017. “From what I understand, alcohol was a key factor,” Griffin notes. Their artistic achievements, however, have finally been resurrected.

“Even if there hadn’t been interest, it’s the least I could do,” Griffin says of exhuming Spike in Vain’s remains. “It’s also fitting that Scat started as a vanity label that unexpectedly grew and, in its September years, is reverting to that with these LPs. The snake has begun to eat its own tail.”