There was no guillotine at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on the night of July 12, 1979, but the crowd was there to see a beheading. The condemned? Disco music. In a scene that resembled something out of a Road Runner cartoon, White Sox officials—hoping to score some cheap points with fans by latching onto a disco backlash pushed by local DJ Steve Dahl—ceremoniously blew a crate full of records to smithereens.

The field was so damaged by the explosion—not to mention the rioting fans—that the second game of a doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers was cancelled. The spectacle is suitably remembered with embarrassment. Still, it reflected a growing sentiment rippling across America’s pop lexicon: disco was going out of style.

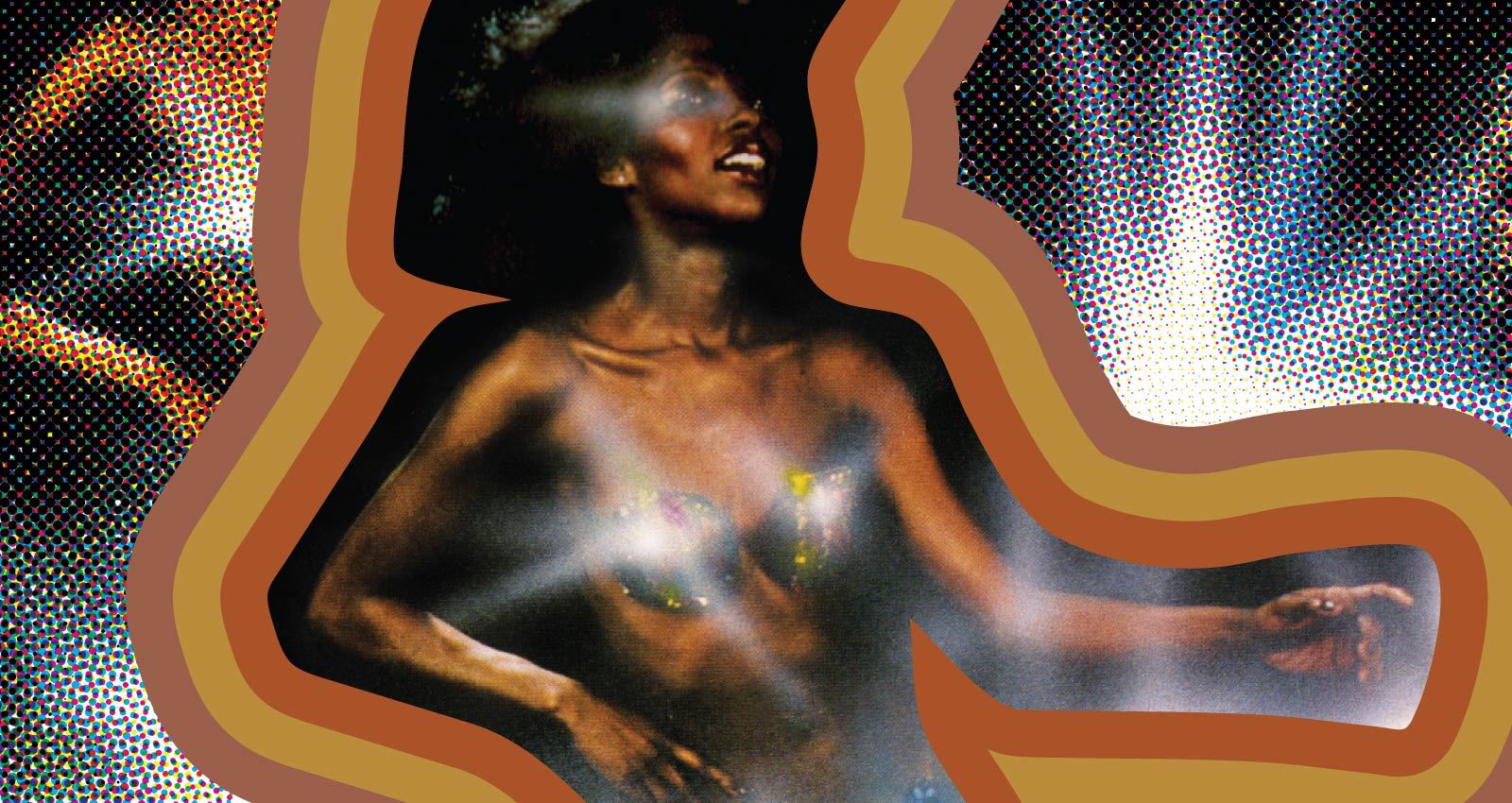

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Such was the backdrop for Sparkle’s one and only album. The self-titled set—recently reissued by Cultures of Soul records—is a full-bodied embrace of disco. In a world where four-on-the-floor singles were being blown to smithereens, the song “Disco Madness” feels like an anthem of musical defiance. Its Chic-style guitar licks, probing bassline, and programmed strings score a celebration of life under the glitter ball. “Disco here and disco there / Disco madness is everywhere,” go the lyrics. In 1979, it might as well have been a war cry.

If the attitude towards disco outside the Hartford, Connecticut studio that birthed Sparkle was mutinous, inside, everything was harmonious. “We were just having fun,” says Harold Sargent, the album’s producer, arranger, and mastermind. Sure enough, with splashes of R&B, funk, and soul in the mix, the album is full of giddy grooves that never stray from the prophecy burned into the group’s moniker: this is music that sparkles.

Sargent had enjoyed something of a nomadic career prior to his work on the project. He joined in his first band while living Cincinnati, Ohio, playing drums behind a certain Bootsy Collins, his brother Phelps “Catfish” Collins, Sargent’s own cousin Robert McCullough, and Philippé Wynn, a singer who would go on to spend five years in The Spinners. That collective would evolve into The Pacemakers before becoming the original version of The J.B.’s, the legendary band that would help James Brown funkify the planet until his death. By then, Sargent had moved to New Haven, settling down with his future wife Ineffie Woods and reconnecting with a father he had been somewhat estranged from.

“While I was in New Haven, they were looking for me to go with James Brown, but I didn’t have any intentions of joining the band,” says the now-77-year-old Sargent, who tells stories in encyclopedic detail, with an immaculate memory for names.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Instead of going with Brown, Sargent joined the Ohio Entertainers—a group that would later change its name to the more groovy sounding The Ohio Hustlers and, in 1973, release the single “Hey, What’s That You Say,” written by Woods. Call it a total accident or plot by some record executive, for some reason never fully explained to Sargent, the band’s early recordings were credited to Wood, Brass & Steel. They embraced the new name, and in the fruitful years that followed, they released two albums: a self-titled debut LP, released on Turbo in 1976, and a second record that wouldn’t come out until 1980, a year after the band had split.

After Wood, Brass & Steel, Sargent began to work behind the music, writing and producing for his own acts. Scratching around for new projects, he looked to a couple of vocalists he knew from around the studio. Barbara Fowler and Linda Ransom were singing background vocals at the time, but both had significant experience. Fowler had been performing since she was a kid and had a formal music education under her belt. Ransom began singing jazz in 1960’s New York, working with people like Peter Duchin and Artie Lee. Sparkle was completed when Ransom’s friend, Dianne Cook, was drafted in to round out the line-up.

To support the trio, Sargent used another group he’d put together. Too Much Too Soon featured two sets of brothers—Keith and Kevin Cloud, and David and John Nevin, as well as Evan Rogers and Carl Sturken. “They were like Earth Wind and Fire to me,” says Sargent with a laugh. “It was a great band. I’d never heard a band like that.” Having encouraged Sargent during the formation of the project, David Casey of New Jersey label Jam Session Records stepped in as Executive Producer on Sparkle.

Needing a place to record, Sargent reached out to his friend Doug Clarke, who owned a studio in Hartford. Lacking the necessary cash, the pair came up with a novel way for Sargent to earn studio time. “Since I didn’t have the money to pay for the studio, he had an old mill building on Church Street in East Hartford. So I’d have to sandblast for an hour and he’d give me an hour’s studio time. We bartered.”

Sargent now had the singers, the band and, thanks to his ability to use industrial equipment, studio time. All that was left was to find enough songs to fill an LP.

“Six Million Steps” was brought to the party by Rahni Harris, a friend of Fowler and one of Sargent’s protégés. The tuneful little instrumental jam was based on a campaign in which activist Andy West ran from Maine to Florida—covering six million steps—to raise money for Muscular Dystrophy. Harris had a rough demo of the cut before bringing it to Sargent, who ended up playing drums on the final version. “Six Million Steps” was first released on the Inspirational Sounds label under the name Rahni Harris & F.L.O. Harris. In the loose spirit of the Sparkle project, it ended up as the album’s opening track.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“When he did the Sparkle project with my childhood friend Barbara Fowler and two other young ladies from the Hartford area, the people who put out the album wanted to add that track to it and that was okay with me,” Harris said in an interview for the reissue’s liner notes. “Harold’s always been there since the day I started out producing records, and he’s followed my career and has always been proud of my accomplishments. I always let the world know that he was the one who made it possible for me to start my career as a producer.”

Recording of the whole album took place in just nine hours over a single day. “It was a hodgepodge of different songs,” explains Sargent. “My wife, I think she wrote two songs on there [“You” and “The Rock”]. Then some of the guys from Too Much Too Soon wrote a few songs. Because Dave [Casey] and Rahni, at that particular time they had some friction, and so I had to mix ‘Six Million Steps.’ My brother [Silver Sargent] sang one of the songs. We were just trying to get it up to fill an album.”

If Sargent makes the process sound somewhat ramshackle, the album is anything but. The upbeat “Let Yourself Go” is a call to loosen your limbs. “The Rock” and “Dabooza” boast the same cosmic swagger as Parliament-Funkadelic with Sargent providing the vocals on the latter, his voice screwed down into a deep baritone. If the album lacks anything, it’s probably a strong presence of Sparkle themselves. Fowler, Ransom, and Cook are only heard on four of the seven tracks, yet all three deliver each performance harmoniously, bellowing out their vocals over the hot arrangements, the singer on lead always snapping into perfect balance with her support.

Sparkle was released on Jam Session Records, but disappeared just as quickly, becoming a curio that could go for as much as $1,500 on Discogs. Perhaps it was because tastes were changing. Sargent knew it to be true—in 1979, he played drums on Spoonie Gee’s “Spoonin’ Rap,” one of the earliest rap records.

Sargent would go on to become studio manager at Sugar Hill Records, further solidifying his place in the birth of hip-hop music. As fate would have it, some of his old Wood Brass & Steel comrades joined the Sugar Hill house band, playing on iconic rap singles such as “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five and Melle Mel’s “White Lines (Don’t Do It).” The late-1980’s saw many of the same musicians form the industrial hip-hop group Tackhead.

Following gigs in New York, New Jersey, Maine, Vermont, and the Massachusetts area, Sparkle and Too Much Too Soon parted ways. Fowler went on to become the lead singer of the group Sinnamon and solo performer; she’s still doing her thing as a part of the vocal trio Hartford Divas. Ransom sings jazz with her band Sugar, as well as performing with Americana band Jeff Pitchell & Texas Flood. It’s safe to assume Ransom ran a musical household: her twin sons Brian Casey and Brandon Casey became half of Jagged Edge, the 2000’s R&B group best known for “Where The Party At.”

After Too Much Too Soon dissolved, Carl Sturken and Evan Rogers became major figures in commercial music, writing and producing for Kelly Clarkson and Christina Aguilera, among others. In 2003, Rogers came across a Robyn Fenty in her native Barbados. Sensing star quality, he invited the star teenager, forever to be known as Rihanna, to the US to record a demo. Rogers and Sturken would serve as Executive Producers on the pop grandee’s first five albums, and the rest is chart history.

As for Sargent himself, he’s still working, still getting busy in studios, still mentoring future stars and teaching drums to kids. He doesn’t work in rap so much anymore, preferring to produce R&B and gospel music on traditional analog four and eight-track records. He’s still enthused about disco music, though—the genre hucksters once tried to erase from history—and gets excited at the suggestion that the Sparkle reissue will bring the album back to light up LED dance floors once more.

“Some disco places are still prevalent,” Sargent claims. “I don’t even understand how they stayed in that long but they’re still around.”