As a young boy growing up in Barbados, Shabaka Hutchings wasn’t immediately drawn to music. There was no bolt of lightning, no key moment that made him want to pick up an instrument. Instead, bored in a music class one day, a teacher asked him if he wanted to play, and handed him a clarinet. “There wasn’t really any choice,” Hutchings recalls. “I wanted to play the saxophone, but they were like, ‘We’ve got a lot of clarinets, so that’s what you’re gonna play.’”

Hutchings lived in Barbados until he was 16, playing clarinet in reggae bands, and creating other improvised forms of music. In Barbados, music wasn’t classified by genre: “If you played an instrument, you just played that instrument. There wasn’t any kind of distinction about what, specifically, you played.” Hutchings started developing an interest in jazz when he moved to Birmingham, England as a teenager. There, he met and studied under legendary saxophonist Courtney Pine. “It went from a point of me knowing nothing about jazz, to practicing with an established jazz musician and checking out the albums he was checking out, and seeing what the music actually is.”

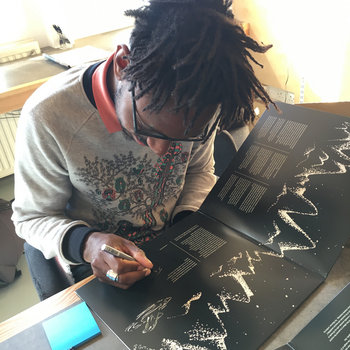

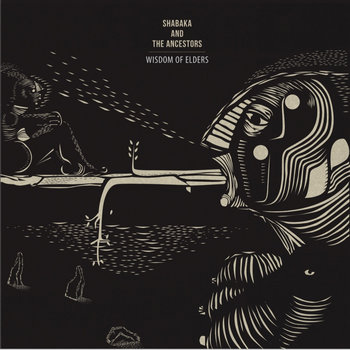

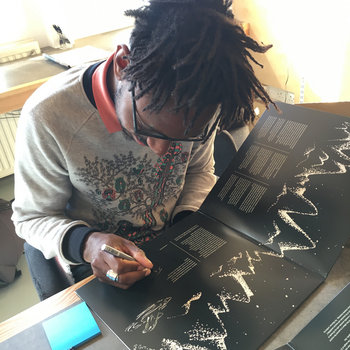

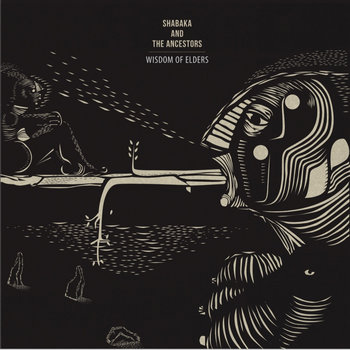

Over the years, Hutchings has performed and recorded with jazz luminaries—the Sun Ra Arkestra, Mulatu Astatke, and the Heliocentrics, among many others. He recorded his new album, Wisdom of Elders, in Johannesburg, South Africa, with a crew of celebrated local composers. We spoke with Hutchings about the LP, the difference between the South African and London jazz scenes, and how current events influence his art.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

What kind of music did you listen to growing up?

A lot of calypso. A lot of reggae. My mum was trying to get me to listen to jazz, but I didn’t want to hear it. I was at that age where I saw jazz in the way that a lot of young people saw it: Old people’s music. There was nothing connecting me to the actual culture of jazz. I had not heard it live in its original setting, so I really didn’t want to hear it. I was listening to a lot of hip-hop, a lot of ‘gangsta rap’ from the ‘90s. That was the thing on all the airwaves. In Barbados, smooth jazz is a big thing—the more accessible, mainstream thing. When I first came to England, that’s when I first started to really learn about jazz, seeing the many facets of it, and understanding how they relate to actual experiences.

What was your impression of the London jazz scene when you first got there?

I moved to London when I was 19. There were so many musicians, all doing specific things, which was certainly overwhelming. If you were into bebop, you could get that. If you wanted improv stuff, you could get that. If you wanted to be in the electronica/noise scene, you could get that. For me, I like hanging out with the people in those scenes. So it wasn’t about ‘I’m gonna find the type of music that I like.’ I wanted to go to all the places.

In hanging out with all these musicians, did they help you find your own creative voice?

Yeah. Some overtly, some not. I feel the creative voice comes from not understanding where you fit within a certain genre or lineage, and having to figure that out over a period of time. The thing that helped me find the creative voice more than anything was interacting within various scenes, having to forge my way, playing all these different styles of music. I record myself a lot, and try to find things that work within all these different settings.

Why did Wisdom of Elders need to be recorded in Johannesburg?

I didn’t intend for this to be a big thing. My ex-partner was in South Africa, so for the last four years, I’d been going back and forth—maybe a couple times a year for a few months at a time, between here and Cape Town—though I’ve been playing a lot in Johannesburg. Coming up on four years, I thought, ‘I need to just record, or have a document of all these experiences I’ve been having.’ When I play over there, the vibe I get is completely electric. There’s nothing I can compare it to in Europe—from my interaction with the guys, to the excitement I feel when I’m playing with them. I’ve come back and tried to explain what I’ve been feeling with these musicians, and nothing can really translate itself. So I thought, ‘I just wanna record what I’ve been up to with these guys.’

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Last January, I was supposed to be on holiday. So when I was supposed to be relaxing, I wrote an album. It was easy, because I had a month. I just worked at my own pace. I did a little bit of composing every day, a little bit of writing, I’d go to a coffee shop and do a couple of hours here and there. Then, at the end of the four weeks, I had the material for an album. So I booked a studio in Johannesburg, and it was a quick thing. I’m a big fan of just getting stuff out. We had one rehearsal, one gig, one day in the studio. It was as simple as that, and I really wanted it to be. I wanted the guys to learn the music and play it right away in the studio. All of the takes, apart from I think one, are first takes.

When I got back to England, I spent a lot of time mixing it and producing it. I spent several days with an engineer, really going into the mix and doing small edits, which you wouldn’t be able to hear when you listen to it. But it meant we could keep the excitement of having first takes. It’s not a rough record. It sounds kinda polished. But you get that feeling of guys just going at it for the first time.

I didn’t allow the piano player to hear any of the music beforehand, or come to the rehearsal, or do the gig. Because he’s an amazing pianist—he’s one of the most incredible pianists I’ve ever heard or played with—but I didn’t want him to play all the shit that he knows. This was the first time he was even hearing the music. I think that added something; he’s just kinda going, saying ‘What can I do on this record?’

Do you have enough material for a follow-up album?

These songs are it. We literally just recorded in a day. We recorded from midday to 7:30.

What are the differences between the music coming out of Johannesburg and the music coming out of London?

With the musicians I played with there, the intent behind the music … there are moments in London where the music gets intense, or you get these tunes that are going toward certain moments. In Jo’burg, the musicians try to get to that space of high intensity from the get-go. So you’ll start the tune, you hear it begin, and there’s something in the air, a ‘sizzle,’ so to speak. It feels like they’re trying to get to a point of ecstasy. They get to these points where the music is really bubbling, and it really feels like a climax moment. It gets to the point where it’s like, ‘OK, we’re gonna stay in this zone then.’

The closest thing is when you hear a [John] Coltrane record, like Live at the Half Note, where he does a half-an-hour-long solo. When you operate within that space of intensity, that’s gonna be the foundation by which you build upon the music. Young musicians now are actually taking that tradition and flipping it, finding new ways to express their ideas, incorporating the elements of jazz into it. In South Africa, you get these real musicians who you hear, like Tumi [Mogorosi], the drummer on the record. I’ve not heard another drummer play like him. That’s the thing that I really enjoy in that scene. That’s what struck me about South Africa; there’s a scene that can produce and actually facilitate completely individual musicians, and have a situation where they’re actually able to survive and keep creating with individuality and feel sustained. It’s not perfect, it’s not like they’re living like kings, but the scene at least allows them to keep being musicians and use that voice.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

How do current events make their way into your music?

I think everything affects music, as long as the music is sincere. With things like race relations in America, race relations in England, or Brexit, I read the news and think about a lot of these issues. I have feelings about them, but I’m not trying to necessarily describe them in obvious terms within the music. For me, music is a way of articulating your feelings on what’s going on in your life. So to me, all of those things will come out. And when they come out, it’s a way of articulating my feelings on all of these issues without orthodox language.

We’re speaking English, and you can understand what I’m saying, but there’s a limit to what the English language can express emotionally. The ways of me expressing frustration and dissatisfaction with the political environments in England and America can only come out through my saxophone. It’s quite an esoteric thing, it’s not obvious, where you hear this and feel rage or feel discontent. You might hear our music, and it might suggest a certain attitude or way of looking at current events, but that’s how things like race relations might manifest themselves through the music.

I feel like this is an interesting time for jazz-related music. I say ‘jazz-related’ because I don’t have a solid opinion on jazz at the moment. It’s been bugging me for a bit. I feel that, regardless of what jazz is, this is a really special time for music that has elements of jazz incorporated into it. It’s special, because it means there are a bunch of young people who are actually coming into contact with elements of jazz. It shouldn’t be forced upon them, but the elements that comprise that music should be imparted. So if they’re listening to music that includes some jazz breaks, or some free jazz—to me, that’s all good. Because that means they might actually come into contact with the original inspirations for that music. There are people ages 25 to 35 getting into Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane.

When a bunch of young promoters are putting on events in unconventional venues, like churches, it feels like the audience coming to that is actually open to that music. For me, that’s a special thing. Ten to 15 years ago, if I were to ask the average person in a bar if they liked jazz, unless they were a bonafide jazz musician, they would go, ‘I don’t like jazz,’ because the image of jazz that they had was quite stigmatized. Oh, ‘Some guy just plays in a pub somewhere,’ or ‘Just music that my parents liked.’ Now, if you ask the average person, they would stop and think about it. Those kinds of blurred lines are interesting and a good thing. That kind of cut-and-dry, either you like it or you don’t, wasn’t good for the scene.

—Marcus J. Moore