Next Wednesday, Shara Worden’s You Us We All will have its American premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival. Though Worden is better known as the leader of the indie band My Brightest Diamond, You Us We All is unequivocally an opera: in collaboration with director and designer Andrew Ondrejcak, Worden has composed arias for a quintet of singers accompanied by an ensemble of seventeenth-century instruments. But supplementing the ageless pedigree of the operatic tradition here is a contemporary gesture that is quite unusual—and perhaps unprecedented—within classical music’s slow-moving recording industry. In advance of the first American performances of You Us We All, today Worden has released the album version of the opera.

Opera is much more often seen before it is heard. An opera house commissions a work, it develops in fits and starts over many years, and it is premiered on a stage. A few years later, if a composer is lucky, a recording might emerge. If a composer is very, very lucky, that recording might lead to future performances. But when You Us We All had its overseas debut in 2013, Worden said in a recent phone interview, “We had three days in Europe when we didn’t have a show, and so we really were like, ‘We’d love to have a recording of this, what should we do?’” Thus, the cast and ensemble gathered in a studio and captured Worden’s music. Releasing an album before the Brooklyn performances of You Us We All is a remarkably sensible move. Why wouldn’t you give potential audiences a hint of how the thing they’re paying for might sound? Opera is not exactly a genre rife with plot twists to potentially spoil.

For most of its four-hundred-year history, opera has existed primarily on the stage. But for the past century, it also has intersected powerfully with recorded media. The first musician of any genre to reach one million record sales was the tenor Enrico Caruso in 1904, singing an aria from Pagliacci. Even if the vast majority of opera recordings released today still feature a dead, European canon, many living composers are echoing Worden in guiding new opera into the world via recordings. Over the past few weeks, I spoke and emailed with several musicians who have released their operas as albums on Bandcamp. They described the practical necessities and artistic benefits of recording contemporary opera, while also acknowledging that to do so conceded essential aspects of their original visions.

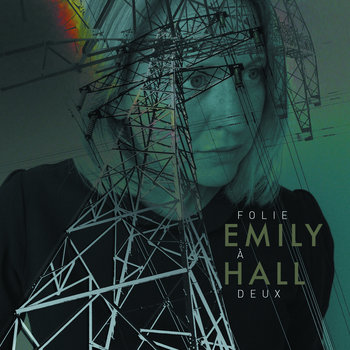

The new opera and the newly recorded album actually have something in common in today’s fractured artistic landscape: they both represent fully conceived musical works realized over lengthy periods of development. As labels such as New Amsterdam and Bedroom Community underscore the importance of the album in contemporary classical music, it only makes sense that projects such as Emily Hall’s Folie À Deux—imagined by its composer simultaneously as an opera and a concept album—emerge.

Compact Disc (CD)

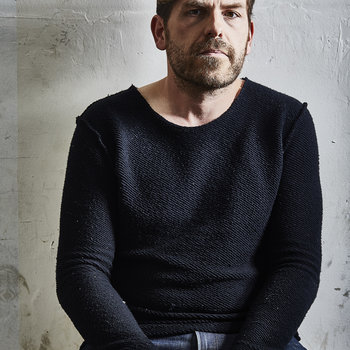

photo by Terry Magson

“I wasn’t really sure what it would mean when I started,” Hall wrote to me. “I just knew it was something I wanted to attempt, an opera/concept album that would be one and the same piece of art.” Commissioned originally by the Mahogany Opera Group, Hall composed for an ensemble of singers and instrumentalists that she viewed as much a band as an operatic cast. As the team workshopped the future staged production, they also crafted a recording. Deftly mixed by Valgeir Sigurðsson and released last July on Bedroom Community, Folie À Deux embraces its identity as a recorded text; it’s easy to lose yourself in Hall’s sonic panoramas, oblivious of a broader narrative unfolding.

“I wanted to, as much as possible, treat the recording as an art in and of itself,” Worden said of You Us We All. Reverb and delay effects bring out instrumental flourishes that might recede from focus in the theater; the music doesn’t stray far from the immaculate production of My Brightest Diamond. “We really pushed the recording, in that medium, as far as we thought we could take it, and still be true to what the music was,” she added.

In the early twentieth century, most of the population of the United States did not live within major metropolitan areas. Recordings, rather than opera houses, thus were the sole opportunity for many to hear an art form then perceived as vital to cultural uplift. Records quickly became a medium through which opera reached an unprecedented cross section of the American public. As the National Music Monthly wrote in 1917, “Why has this great interest and enthusiasm for opera so suddenly developed? Almost every layman will answer with two words, ‘the phonograph.’ People have heard in their own homes beautiful excerpts from the greatest operas, and have come to know their meaning in connection with the stories of the operas.”

By 1921, the Victrola Book of the Opera declared: “The opera has at last come into its own in the United States. In former years merely the pasttime of the well-to-do in New York City and vicinity, grand opera is now enjoyed for its own sake by millions of hearers throughout the country.” (Not that Victrola, which sold thousands of opera recordings along with its own phonographs, necessarily stood as an objective source.) As scholar Robert Cannon describes, though, the rise of opera recording led to the concretization of a star system of singers who ceaselessly replicated the standard repertory. Composers, and especially living composers, were not prioritized. Legendary producer John Culshaw battled with the label Decca for years before they allowed him to record Benjamin Britten’s major opera Peter Grimes; he said, “It seemed to me that a larger issue was at stake, for if we were to abandon so relatively conservative a modern composer we should rule out contemporary music altogether.”

By 1921, the Victrola Book of the Opera declared: “The opera has at last come into its own in the United States. In former years merely the pasttime of the well-to-do in New York City and vicinity, grand opera is now enjoyed for its own sake by millions of hearers throughout the country.” (Not that Victrola, which sold thousands of opera recordings along with its own phonographs, necessarily stood as an objective source.) As scholar Robert Cannon describes, though, the rise of opera recording led to the concretization of a star system of singers who ceaselessly replicated the standard repertory. Composers, and especially living composers, were not prioritized. Legendary producer John Culshaw battled with the label Decca for years before they allowed him to record Benjamin Britten’s major opera Peter Grimes; he said, “It seemed to me that a larger issue was at stake, for if we were to abandon so relatively conservative a modern composer we should rule out contemporary music altogether.”

Today, the money has dried out of major classical labels, and the sphere of Decca and Deutsche Grammophon is left with a handful of stars, unreliable sales, and continued spiraling into irrelevance. Perhaps, then, the composer of contemporary music theatre can re-emerge. Ted Hearne’s The Source—released last week on New Amsterdam—sounds unlike any other oratorio, blending voices, instruments, and electronics into whirling collages to craft a portrait of Chelsea Manning. “So much of the work that I did in the score deals with shades, counteracting any sort of binary argument: there is no right or wrong, there is no male, there is no female, there is a spectrum,” Hearne said when we met last month in a Brooklyn lunch spot. Creating an album out of The Source heightened the radical music of the original staged production. “The ability to master the recording—in a really sophisticated, detailed way—and create that texture, it’s just much higher when you listen to a recording,” Hearne noted. “Especially on headphones, on nice speakers, there are so many things to hear that are in the score.”

Records are also essential for the future life of new opera. If most Americans couldn’t see any opera circa 1915, most Americans still can’t see any new opera circa 2015. You Us We All or The Source might play for a handful of nights in one or two large cities, and then vanish from the stage. I myself have never seen any of these operas in person, but their recordings have profoundly shaped my understanding of contemporary music. Landmark postwar operas, from Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten to John Adams’s Nixon in China, have stayed in the public imagination because they were recorded. When composer Missy Mazzoli was working on her Song From the Uproar in 2011, she told me in a phone interview, “I was thinking, ‘if I let this just evaporate, then that will be so disappointing.’ I know that even in grand operas the recording insures the life of the piece, and pieces that aren’t recorded don’t get performed again and again.” Indeed, the 2012 recording on New Amsterdam provided a vital framework to secure the work’s recent, celebrated run at the L.A. Opera.

, Compact Disc (CD)

Back in the day, aficionados might settle into an Eames chair, turn on their hi-fi equipment, and follow an opera recording with a libretto or score. Even before the advent of radio, Marcel Proust sat in his living room and listened to the local opera house play Wagner via a telephone broadcast system. Recordings stripped away the physical limitations of the theatre, allowing the listener to fully imagine, say, the comedic world of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. As philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote in a 1969 essay, “The music of Figaro is of truly incomparable quality, but every staging of Figaro with powdered ladies and gentlemen, with the page and the white rococo salon, resembles the praline box.” Opera produced in the opera house was trite and precious, unable to properly capture the power of its music; for Adorno, the LP represented a “deus ex machina” that could save the genre by granting its listener complete immersion. Recording, he wrote, “allows for the optimal presentation of the music, enabling it to recapture some of the force and intensity that had been worn threadbare in the opera houses.”

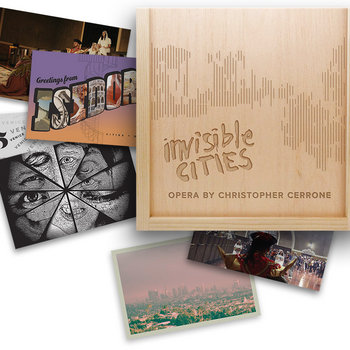

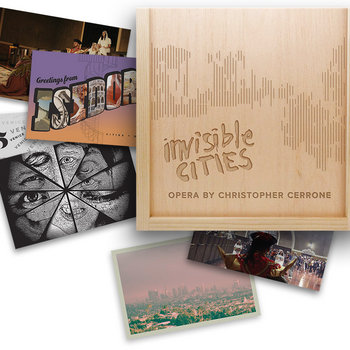

Productions of new opera today, however, stray far from the stale powdered wigs that Adorno described. Perhaps the most unusual—and at the same time, most fitting—recent translation from stage to recording is composer Christopher Cerrone’s Invisible Cities. Based on Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel, Invisible Cities began as an hyper-sensory production: in 2012, the company The Industry mounted the opera’s premiere in Los Angeles’ Union Station, providing audience members with headphones so that they could listen to performers scattered among passersby. Still, the format of that production lent itself quite easily to subsequent recording. As Cerrone wrote to me, “It seemed like a natural extension of the live show. The opera was already being sent into your headphones. You wandered around a space. Why not take that into a larger space and allow any listener to imagine Calvino’s cities?”

Compact Disc (CD)

But opera is inherently as much about visual spectacle as aural immersion. When the genre emerged in courts and public theaters in Italy four centuries ago, elaborate stagecraft along with sumptuous singing guaranteed its future. The composers I communicated with acknowledged that albums represent an unfortunate, but necessary, artistic compromise. The future of their music is secured, while the important work of their collaborators—directors, designers—evaporates. “I think there is some meaning that is lost when you’re only listening to the audio,” Worden said of You Us We All. “It’s an integrated work. I think the piece makes a lot more sense when you see it.”

Invisible Cities was envisioned by The Industry’s director, Yuval Sharon, in the kind of extravagant production that is unlikely to see rebirth; Cerrone acknowledged that in recording, “what is lost is that Yuval’s production so beautiful took to life Calvino’s imaginary world. What is gained is an ability to focus on the musical alone as an object.” (Sharon’s latest project, Hopscotch, seems beyond the realm of possibility for audio recording; it takes place in twenty-four cars that drive across L.A. as the opera unfolds.) The direct political implications of the staged version of Hearne’s The Source—in which projections display footage of faces as people watch the horrifying “Collateral Murder” video released by WikiLeaks—become more subdued and ambiguous in the oratorio’s sonic document.

Emily Hall, having conceived of Folie À Deux as a hybrid artistic work—poised between album and opera—perceived a fruitful middle path between sight and sound. In practice, each version of Folie reveals alternate paths for the listener. “I think the difference is the album can be listened to as a collection of tracks, or as a story, but watching the staged opera it is impossible to avoid the narrative even though it’s fairly open-ended,” she wrote. Even if opera is a narrative art form, the album allows unanticipated experiences to emerge: “I like the idea that a listener may not have a picture of the story and narrative immediately, but it might slowly form over time. I like that a lot.”