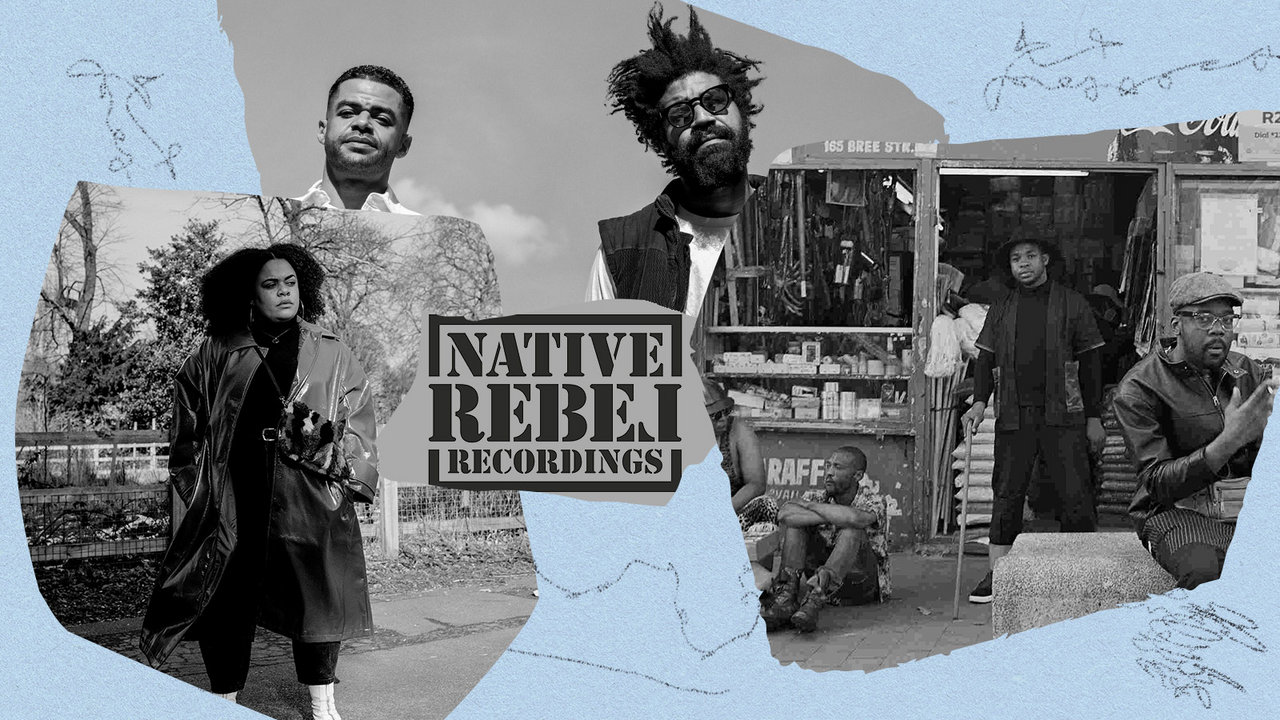

If you’re ever driving through New Jersey’s Burlington County, you might want to leave enough time to cruise past 22 Somerset Drive. Neftali Santiago makes it a point to look at the relatively low-key house at least once a year. It’s there that he carved his own corner of funk music history.

It all began in the late 1960s. After years of travelling from army base to army base with Neftali’s military father, the Santiago family finally bought their first home in the township of Willingboro. It was at this home—22 Somerset Drive—that the young Neftali began his musical journey. And it was here that he developed the drumming skills that would earn him a spot in legendary cosmic funk collective Mandrill.

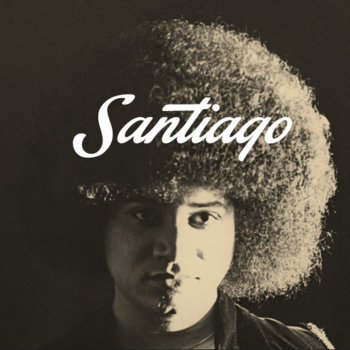

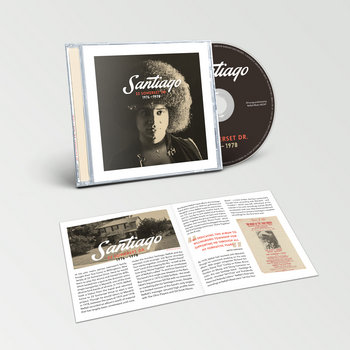

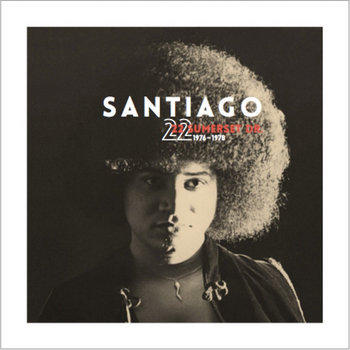

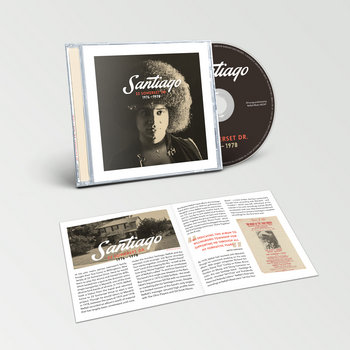

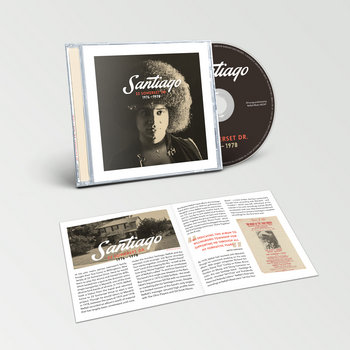

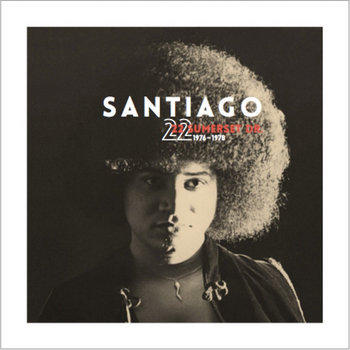

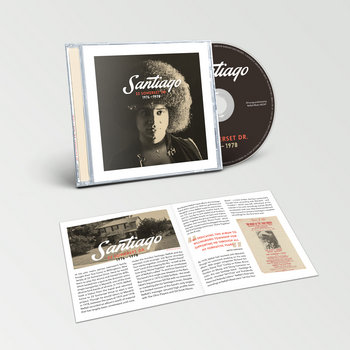

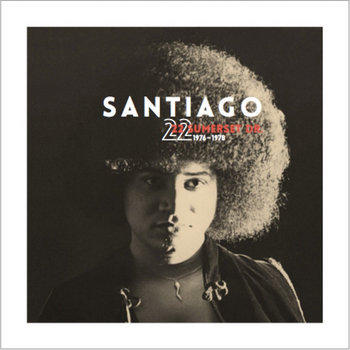

It was also at 22 Somerset Drive where Santiago began forging his own projects, outside the group. He would give the loose collectives names like The Santiago Band, Santiago & Friends, and Neftali’s Beast. And it was at this house where Santiago laid the foundations for an album’s worth of material, recorded during a hiatus from Mandrill in the mid ‘70s that is only now seeing the light of day. When it came time to choose a title for the record, the only option was the obvious one.

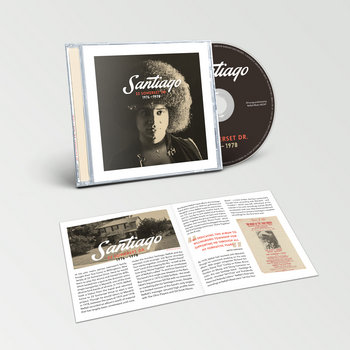

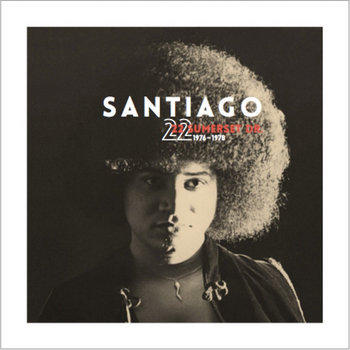

22 Somerset Dr. (1976–1978) collects those lost recordings some four decades after Santiago first laid them down. All funky guitar licks, thick basslines, and JB’s-style horn stabs, this is music with enough bottom to shake any house right to its foundation. There’s also enough bounce to lift a Lowrider right off the pavement. Even in an era when funk was in its prime, the sheer power of Santiago’s arrangements would have blown most of the competition away.

But that never happened. Instead, Santiago rejoined Mandrill in 1978, and his solo songs sat gathering dust. Now, with the music finally out in the world, and despite his ongoing health battles, Santiago is in the midst of planning a new tour and hoping to schedule speaking arrangements to help pass the baton to a new breed of funky architects. Speaking over the phone the morning after a session for yet another new project, Santiago—in a rare interview—opened up about the making of 22 Somerset Dr. (1976 – 1978), and why that old house means so much to him.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

You mentioned you were working on a new project last night. Is it anything you can tell me about?

It’s another project from the past and the present. It’s with Boogie [Cordell “Boogie” Mosson] and Garry [Shider] from Parliament-Funkadelic. We did a bunch of tracks together back in ’94, and they were never finished. They’ve been on the shelf for all this time. Both of them have passed away. I just felt it was time, because I’m listening to what’s out there—Bruno Mars is what they’re calling a funk artist now —and it’s just not doing the genre justice. No one today is playing with the elements we had back in the ’70s. I decided that, even though the tracks weren’t finished together, I was going to finish them now and release them. It’s about 12 songs—another whole album’s worth of music.

Why are you releasing 22 Somerset Dr. now?

Omnian [Music Group] really inspired me to put that project together. When they called me for 22 Somerset Dr. (1976–1978), it was just for the single “Feeling Good.” They wanted to reissue the single. Then, we started talking about “Bionic Funk,” so it was going to be two singles. So then I said, ‘If you want to do that, I’ve a bunch of stuff I never released.’ To be honest with you, 22 Somerset Drive was the only house my family ever owned and lived in. My dad was in the service, so we literally moved every four years from base to base. When he got called to be one of the first Green Berets, he went to Vietnam. When a soldier went to war at that time, the family had to move off base to civilian life. So that’s where 22 Somerset Dr came from. It was the house where I learned how to play to play drums. I just started playing drums immediately; I had no lessons or anything. My brother was a musician, and I just started playing drums one day. It led me to emulate Buddy Miles, one of my heroes, and Michael Shreive [from Santana].

All of a sudden I’m in civilian life, and not military. It was a culture shock. I grew an afro, and it became my signature. The whole Mandrill thing came when I was 19 years old. I was totally not disciplined in school. I was out playing clubs at night. When it came to going to school the next day, it was rough. I never finished school. I think I got as far as 10th grade a couple times, then I joined Mandrill. It was a trip for me, being in that house. This album really came about when I left Mandrill the first time.

The press materials say your family bought that house in the late ’60s. The recordings were made between ’76 and ’78. What was the real significance of the house, and what made you want to name this collection of recordings after it?

For one, I became a musician in that house. Every band I was in actually rehearsed in that house, including Mandrill. My nephew said, when I was trying to think of a title for the album, ‘What’s the one thing that sticks out in your head when you were recording these songs?’ I had to go straight to that house. When I left Mandrill, I put Santiago [the band] together in that house. We rehearsed our show there, so that house really was the center of my music.

[Leaving Mandrill] really left me thinking, ‘OK, well since I’m writing, I might as well go back to putting my own music together, because that’s where I’m at.’ George Clinton approached me, and I took a copy of “Land of Leaping Nono” for Funkadelic to hear. They asked me to join their band at the time. They said, ‘We’re getting ready to become Parliament,’ and I said, ‘Well I think I’m going to do my own thing here.’ I don’t regret that. They did their thing and I did my thing—but my thing, I wasn’t sure what my thing was [laughs].

I was just writing music about what was important to me, and what I was going through at the time was a lot of loss. Leaving Mandrill, when I was on the road, I got a girl pregnant. She had my baby, and my baby looked just like me. So I left my childhood girlfriend at that same time. A lot of these songs are written to her and about her.

After writing all these songs, I went back to Mandrill, because the band just didn’t work out. When my money was gone, the band was gone. I couldn’t hold onto players, because I kept pushing for perfection and a record deal. Although two deals came out of it—one was for the band, and one was just me personally—Santiago had already dispersed, and I became Neftali’s Beast, which was really just me by myself. Listening to all these songs, I really didn’t feel like any of them were finished, so I didn’t want to put them out. Plus, I didn’t know how to put them out.

“Let Out Your Beast” is a real stand out. What inspired that, and how did you get that real bump to it?

That song was out of total frustration at the time. ‘I have to let out my beast.’ I was working with a Chamberlin keyboard. It was before synthesizers. There were nine-second tape loops housed on tape cartridges. When you pressed down on a key, it would start the loop and the tape would spring back. People used those for string sounds back in the ’70s, before there were samplers and synthesizers. I took the strings out, put animal sounds in there, and turned it into a percussive instrument.

“Let Out Your Beast” was an extension of Neftali’s Beast. That was the B-side to a Capitol Records [Neftali’s Beast single] “Land of the Drums.” They put out the single, but they didn’t put out the B-side because it was too personal, I guess. They thought it was too harsh. It was really aimed at Mandrill and the record industry and anybody that did me wrong. I was like, ‘I’m going to let out my beast,’ and that’s what everybody else should do.

It was a real expression song that had to have that kind of percussive power to it. It’s very simple, but it’s driven. That song is really special to me, because I felt that I was able to climax my anger in that song and put it away like, ‘I’m OK now, I can deal with this. The industry is what it is. It’s not going to change. Either I can handle being in it, or I can walk away from it.’ Integrity is a strong word to me. Musically, I wasn’t about to compromise, and I don’t think musically I compromised at all on 22 Somerset Dr.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

This has a real funk sound. You could probably file it next to some of the George Clinton stuff, and maybe Zapp and Roger Troutman.

George Clinton was a big influence. Funkadelic, they were all great friends of mine. We toured so much together on the road. We must have done 90 or 100 gigs together. We became really good friends, so the Mandrill sound kind of rubs off on them and the Funkadelic sound rubbed off on us. As a writer, I took it all in. Funkadelic definitely influenced my writing. I think because I was working with [arranger] Joe Bird, the horn arrangements came from not really a P-Funk place, but more like a powerful Mandrill blend. At the time, that P-Funk horn sound wasn’t really developed yet. It really wasn’t happening until the ‘80s and Parliament. Funkadelic wasn’t doing horns at the time. We created our own power horn sound, which I think is just excellent. I couldn’t be more happy with the horn sections. Joe Bird is just a phenomenal arranger. I wish I knew where he was. I haven’t seen him since the ’80s.

You mentioned this music coming around again with people like Bruno Mars, but I think also you can hear it in guys like Dam-Funk and Terrace Martin, and even in the hip-hop lineage of G-Funk and people like YG. How much do you follow the sounds as they’ve developed today?

I think that the funk genre should not disappear. I think that any attempt to keep it alive is positive. Although I have my opinions on the sounds of the bands that you talked about, I keep up with anybody with any kind of funk connected with them. Not that I consider myself a funk artist, per se, I just happen to be one of the innovators of the genre. Everybody talks about me being a funk artist, which I am, but I’m much more than that.

That whole thing is evolving somewhere else. There isn’t a Mandrill band out any more, and most bands that are playing funk from the ’70s—it’s not really a strong attempt. The strongest attempt I heard was Lowrider, which was the original War band without Lonnie Jordan. They sound excellent. I figure I really should do this one more time. I really want to support the album and support Mandrill music, and just do it once. I don’t want to prolong it; I just want to do it one time.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Do you know whatever happened to the house at 22 Somerset Drive?

Almost every year I go by it, check it out. I tried to buy it actually. It’s not for sale right now, but if it was, I would definitely buy it. Every time I go past that house, every time I go to New Jersey, I have to go see it. I still have family in New Jersey, so they don’t live too far from that house. My dad was going to sell me that house back in the day—when I was rehearsing with Santiago in the house—for $8,000. I really wish I’d bought the house, because it’s such a piece of my history. I think at some point that house will be mine again. I want it to be.

That group of songs, 22 Somerset Dr.—I tell you, man, it just blows me away. I think they did such a good job of presenting the package. I think it presents me as an artist really well. They took the time to master it well. It’s my heart, bro. It’s real piece of me! You don’t get that from artists nowadays.

Do you think modern listeners will embrace the album?

I think people are going to like it. I enjoy listening to it. I can’t listen to Mandrill music, because it just brings back too many memories. I can listen to 22 Somerset Dr. I can listen to every song now and get something positive about where I was at the time. They all bring me back inside of that house. There were some good memories, but there was a lot of bad memories, too. Like I said, it’s a piece of my heart on vinyl. I think the people are going to pick up on that, and bypass whatever imperfections that I see are coming from the album. I have to let it go, I have to release it.

—Dean Van Nguyen