Though they’re widely regarded today as forefathers of a certain strain of progressive, folk-inflected American black metal, West Virginia’s Nechochwen never set out to play metal at all. At first, founding member and songwriter Aaron Carey just wanted there to be better music on the CD shelves at history museum gift shops.

“I’d always buy these cool books, but the music that I’d see at those places was kind of cheesy sometimes,” Carey says. “I thought, ‘I can do better than this.’ I may not be able to write books this well, but I think that I can write music better than this that’s about the things that these places are trying to talk about.”

Carey’s interest in local history began when he was still a teenager, when his mom made an offhand comment about their family’s Native American heritage—something Carey knew nothing about at the time. It turned out he had descended from prominent members of the Shawnee and Lenape tribes, but over the generations, his family had all but stricken their genealogy from the record.

“I started asking [my mom] all these questions, and she said, ‘You should ask your grandfather,’” Carey recalls. “So I did, and he said, ‘Well, you know, we weren’t allowed to talk about it when we were kids. That was the worst thing you could be. That was the lowest of any race or ethnicity. You didn’t admit to that.’ If you were an American Indian on the census, you couldn’t own land in West Virginia until like 1965 or something. There was no incentive to mark that on someone’s birth certificate, and there was a lot of general assimilation.”

Seeing the lack of Native pride in his own family, as well as the relative invisibility of indigenous history in his hometown, Carey started reading. Crucial volumes by writers like James Alexander Thom, Allan Eckert, and John Sugden shaped his worldview. Around the same time, he discovered heavy metal and started playing in bands. Friends dubbed him “Nechochwen,” a Lenape word meaning “walks alone.”

In 2005, when he started writing the music for the first Nechochwen album, Carey was playing in a more straightforward death metal band called Angelrust. That fulfilled his need to play heavy music, so the songs he wrote for Nechochwen leaned on his background in classical guitar instead. When Angelrust collapsed a few years later, it cleared a path for Carey and collaborator Andrew D’Cagna to transform Nechochwen into the band it is today.

“At first, [Nechochwen] was a diversion,” Carey says. “It was something to do on the side while we had an extreme metal band. But we’d always have these conversations. ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to do something like Ulver or Arcturus?’ Something that’s more like the underground, experimental, progressive black metal that we really liked. Because Angelrust wasn’t that.”

Nechochwen have blazed a singular trail in the years since, fusing classical guitar, traditional Native American instrumentation, and Appalachian folk music to melodic, atmospheric black metal. Their lyrics have also consistently shone a light on the oft-forgotten history of the Eastern Woodlands Indians. Carey and D’Cagna recently walked us through their peerless discography as they prepared for the release of their fourth full-length, Kanawha Black.

Algonkian Mythos

“I wanted to basically write historical narratives in instrumental musical form,” Carey says of Algonkian Mythos, Nechochwen’s entirely black-metal-free debut. “The target audience—not that it wasn’t for people who were into metal—but it was more for people who were into the history scene, like reenactors and people who work in museums and gift shops.”

With D’Cagna producing and providing background vocals, Carey set about transcribing a few key chapters of local indigenous history into song—mostly, though not exclusively, on classical guitar. There was a darkness to a lot of this history, which Carey worked hard to get across without utilizing sonic heaviness. “Coffin of the Flesh” was inspired by an Iroquois ritual that involved scraping rotten flesh from corpses and reburying the bones. “That’s pretty grim,” he says. “It’s metal, but it doesn’t have to be a metal piece. I wanted to get the dark vibes I’d played for years in metal bands, but in an organ piece.”

Elsewhere, Algonkian Mythos is stalked by tragedy. “Gnadenhutten” evokes a 1782 massacre of 96 unarmed Christian Lenape Indians by a white militia from Western Pennsylvania. (“I thought, ‘Wow, this is technically the largest massacre in American history, and I never learned about it in school,’” Carey says.) “West Across the Missi-Theepi” is a heartrending piece about the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which forced countless Native Americans from their homes. At its best, Algonkian Mythos brings the past vividly into the present. No song illustrates that better than “Pilawah,” one of the few tracks on the album with vocals.

“Pilawah is a Shawnee word for turkey,” Carey explains. “I found this in a book of a woman who had been captured when she was little, brought into the Shawnee tribe, and years later she escaped and was interviewed for a book, when she was in her 60s or 70s. They asked her what she remembered from those times, and she said they used to sing this song to the children, kind of like a lullaby-type thing. And they wrote out the notes. That was, I think, in the 1840s or 1850s. Someone wrote out these notes with these syllables from someone who was a little kid in the late 1700s. I thought, ‘That’s amazing that that survived, I’ve got to recreate that and see what that would sound like.’”

“Winterstrife”

“It’s a blip, but it’s a significant blip,” D’Cagna says of “Winterstrife,” the song Nechochwen contributed to the 2010 compilation Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer.

“It’s probably the most significant blip in the history of what we’ve been doing,” Carey echoes. “Things were kind of grinding to a halt in [Angelrust]. It’s 2008 at this point, and this other band is kind of falling apart, and this was something different from the subject matter on [Algonkian Mythos], but I thought it was a cool idea.”

The comp asked contributing bands to write a song inspired by Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Carey imagined a Depression-era West Virginian struggling to feed his family, gazing out into the foggy mountains as his children cry from hunger. Once he laid down the skeleton of the song, he realized it was begging for heavy guitars and drums.

“That’s not what this project was intended to be,” Carey says. “But is that a good way to think? You didn’t intend to do this, so let’s never do it, because of some self-imposed rule? That’s kind of dumb.”

In the end, Carey plugged in his guitar, D’Cagna joined on drums and bass, and the rest was history. Nechochwen was a metal band.

Azimuths to the Otherworld

The first Nechochwen album to incorporate black metal elements was 2010’s Azimuths to the Otherworld. It was also the first album that saw D’Cagna in the band as a full-time member.

“Doing that song for the comp, that sold me,” he says now. “Once I heard that recipe of what I felt that music could be, with [Aaron] writing that way and adding the heavy element, I was on board, man.”

In retrospect, Azimuths feels like a baby step in the direction of metal, at least when compared to where Nechochwen would ultimately end up. Still, the compositional liberation is palpable. Carey and D’Cagna are free to explore, and their early feints at the sound they would soon fully embody are fascinating. Carey’s storytelling is also more exploratory, as he dives into thousands of years of history left behind by the mound-building peoples of the Ohio Valley.

“I started finding out about local spots that aren’t in any books,” he says. “You just find out from locals that that’s what this was. ‘We find arrowheads here, we found pottery here.’ That got me down this rabbit hole of all this Adena and Hopewell and Fort Ancient stuff, and in finding the modern tribes that they’re most closely linked to.”

Carey also says that fans of Ancient Aliens can read between the lines of Azimuths to the Otherworld: “I got fascinated with some of this stuff and how it only makes sense from the air. The Native perspective I’ve gotten from that was that they had help from another planet.”

Oto

If previous Nechochwen releases had mostly presented their Native American themes as objective history, 2012’s Oto EP emphasized the connection of those themes to Carey’s personal identity. Bifurcated into an acoustic side and a black metal side, Oto bears the marks of the community of Native people that Carey was embedded with at the time.

“The Loyalhanna Band in Pennsylvania was a group that I was a part of since the mid-to-late ’90s,” Carey says. “It was people with Shawnee, Lenape, Cherokee, and Wyandot ancestry, and [around Oto] we would get together about once a month and work on language, keep traditions and Thanksgivings together, study dance, and I would help them work on music from various sources. We were just trying to preserve that history and keep alive something that was prominent a couple hundred years ago that isn’t prominent at all anymore in that area. My mom was real sick at the time with cancer, and I think it kind of helped me hold things together. I was focused on something bigger than myself, and it was fascinating to learn more about language, learn more about tradition.”

Thanks to his work with the Loyalhanna Band, Oto also saw Carey writing much more comfortably in indigenous languages. “Up until this point, we basically had word lists, but no elders to tell us, ‘This is how to form these words together, this is your grammar and syntax’ and stuff like that,” he says. “You could know 500 words and never be able to speak a sentence. For the first time, I was actually speaking in sentences and having transactions and having conversations and stuff, and that was super inspiring, so I wanted that to come through on some of the songs, because I was never knowledgeable or confident enough on the albums before that.”

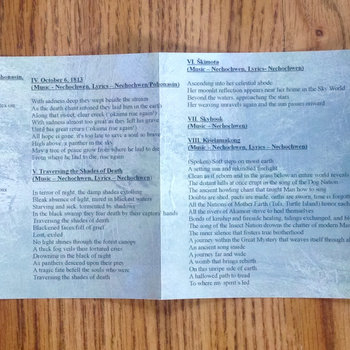

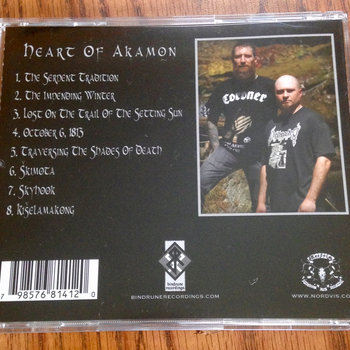

Heart of Akamon

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

“[Oto] was probably the biggest time of spiritual growth and awakening for me, and it came out big time on that album,” Carey says. “You may notice just from listening to it that I was carrying around a lot more anger and resentment and bitterness [on Heart of Akamon]. I was very distracted from where I wanted to be spiritually at that time. I lost my mom, I was going through a divorce, I had a young child, I was not especially financially stable at the time. All of that, I think, fed into the riffs.”

Heart of Akamon was certainly the heaviest, most aggressive album Nechochwen had released up to that point. Its cover art depicted a battle between Native Americans and an army of colonizers, and much of the material had a pointedly warlike feel. Carey’s rigorous approach to historical accuracy was unwavering, but he had figured out a way to combine it with his own righteous anger and frustration in a way that made Akamon feel more visceral than earlier Nechochwen releases. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was a critical and commercial breakthrough for the band.

“When it came out, it freaked me out,” Carey admits. “I was on a trip. I forget exactly where I was, but we started getting [a lot of] sales on Bandcamp. Prior to that, we’d just have them trickle in sometimes. But it’s not just about selling the album or making money off it. These things are there after you’re gone. I want to put something out really good, and I hope that people enjoy it.”

Kanawha Black

Vinyl LP

In the seven years since Heart of Akamon, Nechochwen have released a rarities compilation, contributed tracks to a pair of excellent splits, and put out their first live album. Still, Kanawha Black feels like it was a long time coming. It was well worth the wait.

“We never know what we’re doing until it’s done, basically, but when [Bindrune Recordings co-owner] Austin [Lunn] was asking what it sounded like before he heard it, I remember saying everything is more extreme,” D’Cagna says. “The heavy parts are heavier. The faster parts are faster. All the organic stuff seemed more on a progressive note than before, less of a traditional, classical sense where a lot of Aaron’s ideas come from. All the elements that make Nechochwen music what it is, there was another notch now.”

There aren’t any instrumentals or fully acoustic tracks on Kanawha Black, but its seven songs represent the full spectrum of what Nechochwen can do. The opening title track and album closer “Across the Divide” are two of the finest songs the band has ever written, each one epic in scope, towering in scale, and powerful in execution. The meditative “I Can Die But Once” and the martial “Generations of War” represent two sides of the same coin, one that’s rooted in the history, geography, and genealogy that Carey has dedicated his life to studying. With Kanawha Black, he bridges West Virginia’s distant past to its difficult present and its uncertain future.

“Kanawha black is a type of flint you can find throughout West Virginia,” he says. “Studying arrowheads, and studying [this region’s] archaeology, that term comes up a lot. ‘Black’ is an archaeological term for a type of stone, but I also think West Virginians have a kind of a black cloud over them, ancestrally, with a lot of darkness. A lot of migration, a lot of bloody history up and down the Ohio River, but also in modern times with poverty and opioid abuse. We have some dark issues in that same region. I’m not trying to be negative about it. I’m just being observant. What is it about this place that we’re from, that even in ancient times it had a really dark background to it?”

Kanawha Black doesn’t provide any easy answers to that question, but like the rest of Nechochwen’s work, it provides a lens to consider it through. Carey wants listeners to have to think hard about the history of the land they call home.

“One of the underlying things we want to get across is knowledge and exploration, and thinking about things you wouldn’t normally think about, with a culture that’s been here much longer than our predominant culture nowadays.”