When Nazar arrived in Angola in 2007, it had only been five years since the country’s 27-year civil war ended. The preceding decades were devastating, ripping families apart—including Nazar’s own—and resulting in a death toll of over 500,000. In Belgium, where the electronic artist lived until he was 14, the conflict was difficult to comprehend. So was the fact that his father, a high-ranking member of the opposition, didn’t live with the rest of the family, who’d resettled from their war-torn homeland to Europe. Once he returned to Angola, Nazar was thrust into a series of conversations which began to reveal the war’s effects.

Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

“The moment I got there, my dad and mother reconnected us with the rest of the family,” says Nazar over a video call. “My parents and siblings would talk a lot about the past, the history of politics, and their experience of the war. Sometimes they would repeat stories but they would add more detail as they began to feel more comfortable. It got to a point where I almost felt like the memories were mine.”

Guerilla, Nazar’s debut album, folds these stories into his “rough kuduro” sound: the 26-year-old’s take on a form of popular Angolan electronic music, which emerged during the civil war. Kuduro is usually characterized by propulsive rhythms, breathless rapping, and even quicker dancing. While Nazar’s tracks convey the same relentless forward momentum, his beats are less sure-footed, often wrapped in fog-like noise. He peppers the works with drifting ambience and field recordings which, taken as a whole, plays out like a fever-dream dispatch from the former Portugese colony. Nazar’s music is far from the mainstream kuduro he heard at family and community parties in Belgium (the tunes were always five years out of date, he jokes). Upon arriving in the country itself, he encountered the street style of artists such as Os Lambas and Bruno M. “It was a huge shock,” he says. “A good shock.”

Nazar’s earliest musical experiments in 2007 aped the “raw electro” style popularized by artists such as Sebastian and Justice, whose battery-acid distortion lingers in Guerilla’s fizzing atmospheres. He says these early experiments helped him cope with homesickness while navigating his new and unfamiliar West African home. Gaining familiarity with his Angolan surroundings, Nazar started writing kuduro beats using a Fruity Loops Studio demo on his father’s laptop. Tracks couldn’t be saved and returned to later so the young producer would often work for hours uninterrupted.

Guerilla is denser and more textural than its influences. Opening track “Retaliation” begins with softly chirruping birds before ominous bass and panoramic synths introduce an almost immediate sense of dread. The mood rarely lets up, from the tightly coiled rhythms of “Diverted” to “Arms Deal” whose syncopated kicks are smothered with buzzing sounds. “Bunker,” which features vocals from Hyperdub DJ and curator Shannen SP, draws inspiration from a story Nazar was told about his older sisters who sought refuge in a hotel with foreign journalists during the 1992 election. “That was one of the few buildings that didn’t have the squads hunting down opposition,” says Nazar. “The experience gave me anxiety. In 2008 [the first elections since 1992], we [Nazar and his family] slept on a huge mat in the living room next to the TV, just to make sure everyone was together.”

At times, Guerilla’s sense of place is so keen that it feels like you could step into its compositions. “Immortal” starts with what sounds like a distantly rumbling train and the click of cicadas on a hot summer’s evening. Nazar captured many of the record’s environmental sounds using iPhone memos in Angola, while others were sourced remotely through downloading YouTube videos and ripping the audio. Elsewhere, this method of documentation and presentation veers into more explicitly personal territory. Backed by lullaby-like synths, “Mother” features a recording of his own mother recalling the day she joined the independence movement as a 14 year-old, an event which led to her meeting Nazar’s father. “I asked her to make the recording in Umbundu [a regional language],” he says. “I didn’t want to translate sounds for the Western world. This is the language you would hear walking around villages and towns.”

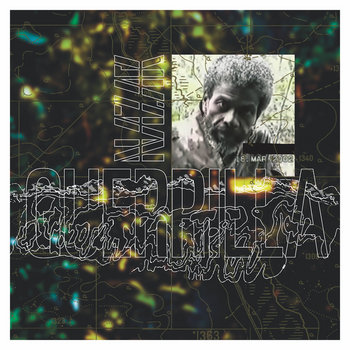

As much as Guerilla is about processing his family’s experience of the cataclysmic civil war, the album is a meditation on Nazar’s relationship with his father. He occupies space on the album cover and his voice can be heard on the final track, “End of Guerilla.” During the pair’s long road trips around Angola, Nazar witnessed firsthand how the war still haunts the country’s landscape, particularly in rural areas. Abandoned tanks and crumbling ruins waymark regions Nazar refers to as “literally forgotten.” Reflecting on the pair’s relationship, Nazar describes his relationship with his father as “good” but still a “work in progress,” partly because of the gap which exists between them because of the civil war. “I feel like for him, it’s probably OK,” he continues. “But because I grew up in another culture, I feel like there’s things lacking.”

What Guerilla makes clear is the rich cathartic power of sound. “In Angolan culture, it’s common to dance to sad topics,” says Nazar. “Even a komba, the funeral, feels like a party.” Like the stories his family told—punctuated by laughter even at their darkest moments—or the birth of kuduro, Guerilla isn’t just a means of processing the Angolan civil war, but an opportunity to transcend its trauma.