Photo by ROOT

Photo by ROOT

For Palestinian instrumental hip-hop artist Muqata’a, sampling is political. He builds on a foundation laid by genre originators such as Public Enemy’s Hank Shocklee, a producer who introduced ‘80s kids to Macolm X and Angela Davis by splicing samples of their speeches into his legendary productions. “Sampling […] forces us to go backwards in history,” said Shocklee in 2006; it’s both an opportunity to establish a musical lineage and a way to sustain ideas. Like Shocklee, Muqata’a uses the production technique as a tool of celebration and defiance, a means to ensure the past echoes into the present with chest-rattling potency.

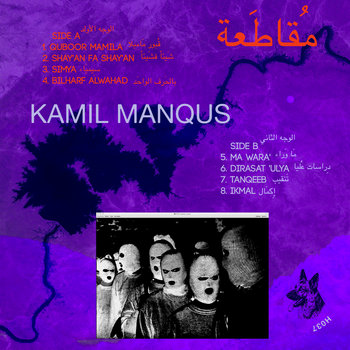

Vinyl LP

Across five impressive albums, Muqata’a has honed his approach as a producer (previously, he was a rapper under the alias Boikutt) while adopting an omnivorous approach to sampling. On his previous record, 2018’s Inkanakuntu, the sound coalesced into a series of form-bending songs; bruising kicks swirled amidst fragments of classical Arabic records sourced from his parents’s and grandparents’s collection, all of them coated in thick and uncomfortable distortion. Nostalgia met upheaval on tracks which were just as likely to set off a rave as inspire a hearty political discussion. “It’s a reflection of everyday life,” the Ramallah-based artist says soberly over Zoom. “Nothing is in order.”

Muqata’a’s new album Kamil Manqus كَامِل مَنْقوص, recorded throughout 2019, is his most refined and personal, its eight bristling compositions united by samples of human voice. These, he explains, are intended to invoke the “voices of ancestors,” and relate to an Arabic alphanumeric science which combines letters and numbers to communicate with the “immaterial world.” In this musical equation, the voices are the letters and the pummeling beats are the numbers; together they elevate one another. It might sound like a heady approach but the result is hugely evocative. On “Shay’an Fa Shay’an شَيئاً فشَيئاً” which translates to “little by little,” a low-slung groove and needling synthline slowly build before ending abruptly with a jazz-chord flourish. The negative space left by the percussion brings a bustling field recording into focus, sourced while Muqata’a and many others were stopped for hours on the Palestine border with Jordan. “People were demanding their human right to travel freely,” he recalls. “A kind of resistance was taking place.”

At times, the album sounds like the disrupted radio frequencies from which Muqata’a took inspiration. Static seems to squirm not just in the pockets of space between the warped rhythms, but across the very soundwaves of its scrawling melodies. “Dirasat ‘Ulya دِراسات عُليا,” the title of which refers to a “higher level of awareness,” is the noisiest of the lot; feedback functions as melodic percussion alongside a scurrying hand-made breakbeat. Elsewhere on Kamil Manqus كَامِل مَنْقوص, grotty sonics are rendered with hi-fi precision, achieved through a variety of exacting production techniques. Muqata’a frequently micro-edits his sounds, zooming in, dissecting them, and blowing the compression and gain up to ear-splitting levels. This, he says, is a response to the tumultuous physical environment characterized by seemingly random, often violent eruptions of noise.

The mechanized soundscapes, which often seem on the cusp of collapse thanks to their mass of aural glitches and artifacts, loop back to both Muqata’a’s artist name, which translates broadly to “disrupt,” and the album title, which means “perfect imperfect.” He refers to the situation in Palestine as “stagnant,” both politically and economically. “It’s important that we attempt to break that,” he asserts. “Glitches and mistakes; to me, that’s what makes art, but it’s also what can help break this stagnation. Be the glitch in the system, because the system’s working against us.”

The approach seems to be working. In 2018, club live-streamers, Boiler Room, released Palestine Underground, a documentary about the company’s first Ramallah event. More recently, Muqata’a, alongside artists Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas (the duo behind the album’s eerie artwork), started Bilna’es, a publishing initiative which will platform homegrown music, performance, and web projects. Its first release, Dakn’s too low, too far, came in November 2020, an ominous and discomforting drone record of strange harmonic and ambient textures. Each of these projects is an opportunity to tell the Palestinian story in all of its multitudes; a chance for listeners to feel it reverberate through their own bodies.

Kamil Manqus كَامِل مَنْقوص isn’t a party record, but it does contain moments of attention-grabbing, almost giddy abandon. The closing track “Ikmal إِكمَال” (“completion” in English) whips along at a blistering drum & bass clip, a showcase for Muqata’a’s instinctive dancefloor sensibility. Remembering performances in Ramallah itself, at bars and cafes often forced to close early by police, he says, “it really feels like you’re communicating; it feels like you’re starting something.” As the oft-mentioned “godfather” of Palestinian hip-hop makes clear, music is a way to bring DJs, rappers, producers, and artists together; perhaps, more than anything, “it’s about community building” within a circumstance of extreme instability.