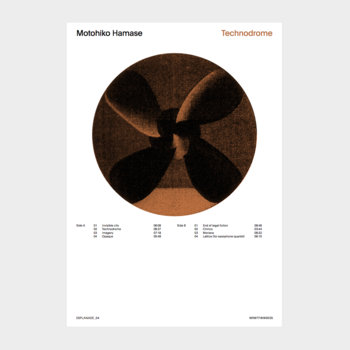

Motohiko Hamase spent most of the ’70s in Japan, playing bass in jazz ensembles, but by the 1980’s, he was focusing more on his own compositions. He was broadening his influences, discovering Jaco Pastorius, Peter Gabriel’s IV, and Public Image Ltd’s Flowers of Romance. In 1993, he released Technodrome, by far his most adventurous record to that point. He’d opted to work alone for the first time, hoping to communicate something drawn from deep within himself. The entire lonely process took him three months.

Pulsating rhythms and techno-like repetition are key to Technodrome, an album designed more to engage with a listener’s unconscious mind than inspire them to dance. With its haunting synths, unrelenting mechanical funk beats, and unsettling bass leads, it feels like the grim soundtrack for everyday life in crumbling, post-apocalyptic cities.

“It is quite an enjoyable experience to perform live with [other] players while listening to each other’s playing, and reacting to it, which [results] in the fruition of music,” Hamase says. “But an aspect of musical constraint exists within the jazz tradition as well. I wanted to explore a new juncture of improvisation. What I was trying to achieve was to formulate this phase of poetry into a musical piece.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Before he began work on Technodrome, Hamase had begun working on the song “Lattice,” intending it to be performed by a saxophone quartet. But as he started listening to experimental and ambient artists like John Cage, Brian Eno, and Jon Hassell, he switched gears. He liked the way Eno’s Nerve Net and Hassell’s City: Works of Fiction deconstructed house music. Technodrome was his answer back, an album that uses unsettling ambient music as its driving engine.

On “Invisible City,” Hamase builds a bubbling bass loop that throbs robotically, backed by lightly tapping percussion and an orchestra of intermittent synthesizer chords. On “Chirico,” Hamase uses synthetic clanking sounds that sound like beaten sewer pipes to create a dissonant, staccato rhythm as smooth, cresting waves of white noise pulse through the song, disrupted only by his fretless bass’s unpredictable path. “Lattice,” an unnerving saxophone piece, brings Technodrome to a close, an unusually organic ending to a synthetic solo endeavor.

Hamase recorded the album using a primitive version of Pro Tools on a Macintosh FX computer, with only eight channels, and no plug-ins. He played both fretted and fretless bass guitar and a Korg Wavestation synthesizer, and used an Ensoniq DP/4 to add effects to any of the tracks. The recording process became something of an internal journey, one where he spent time analyzing the philosophy and mechanics of his creative process. He imagined his state of mind to be “a depersonalization condition in the psychopathological context,” similar to an out-of-body experience.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“I had an idea where, if I initiated a process of assembling images that I dreamt up that resulted in composing musical pieces, it would enable me to be transported to a new musical world that would be difficult to carry out through a collaborative process,” Hamase says. “Within this process, I wanted to explore a new juncture of improvisation.”

He saw what he was doing in contrast to the mindset of Japanese jazz critics of the time, who thought musical magic could only happen when musicians jammed together. On his original liner notes, Hamase declared Technodrome a challenge to this notion, writing that he wanted to destroy the antiquated idea that “Improvisation means existence.”

Technodrome also became a testament to Hamase’s fascination with the intense beats and bass sounds of house music. He used the genre’s fondness for the repetition of short phrases to express a sonic sensibility that would be familiar to people living in modern cities.

“I see composing to be an endeavor, that I am able to accomplish the creation of a piece of work based on my own image, and I do not think that it is something that was brought upon by some other entity other than myself,” He says. “I think that since both John Cage and Jon Hassell were able to attain another dimensional state of mind called dissociation as a source of their imagery, they were able to expand their music to a new dimension, and I consider my own works to be alike as theirs.”