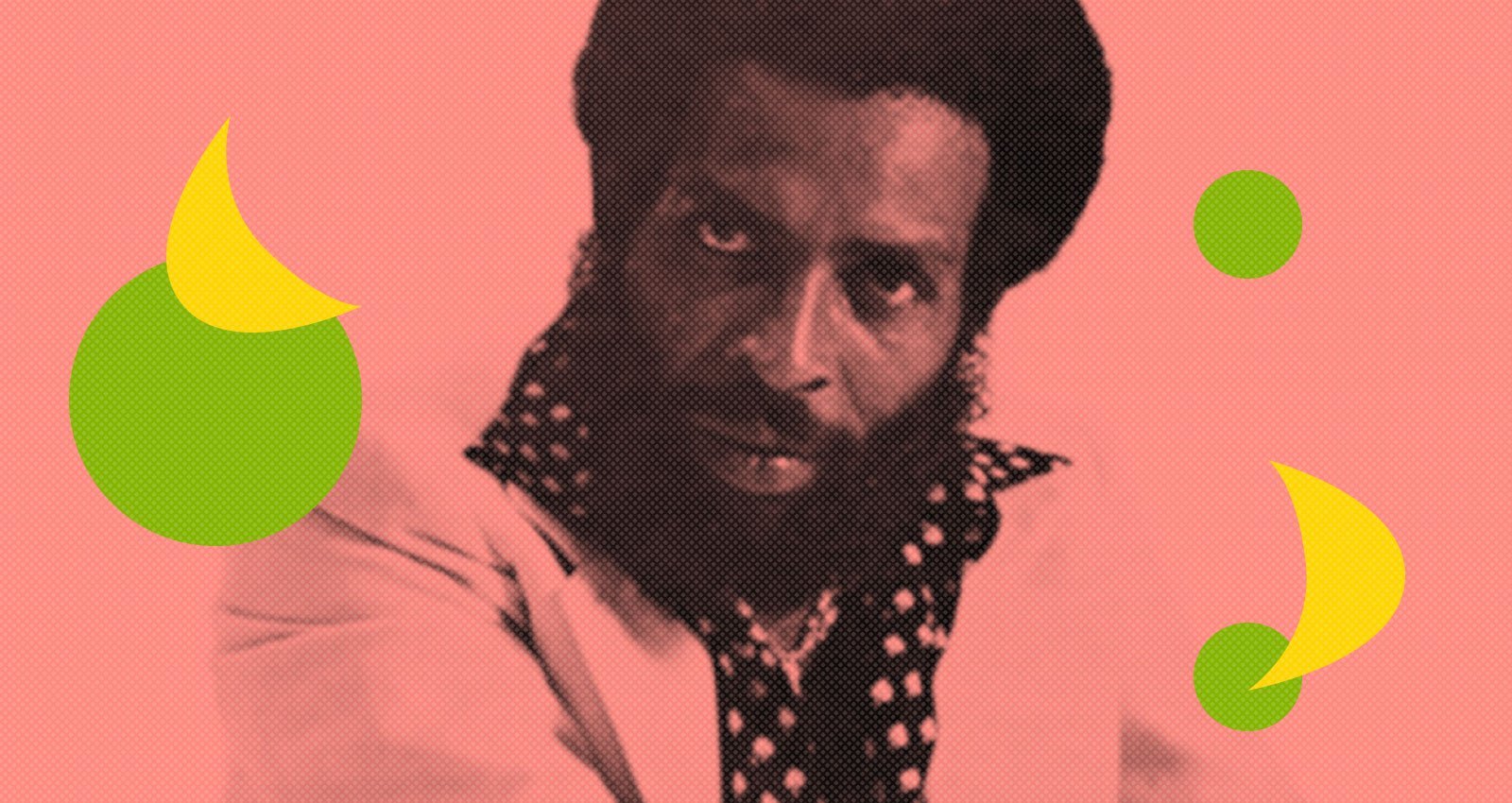

In the early 1980’s, Miami musician and producer King Sporty (born Noel Williams) reached out to Benji “The Mad Bomber,” the resident DJ at popular dance club Inferno. Williams wanted to shoot a video for “Shoot it from the Hip,” his recently released disco-funk collaboration with Bobby Caldwell. While there, he watched as Benji riled the crowd up with call-and-response, shouting phrases like, “Get on the floor,” and “There’s a party over here,” but he would always come back to a single phrase: “Move something.” It was a phrase Benji had heard on the streets of Miami from friends. It was meant as a way to motivate each other to do something positive. Benji thought it was a good way to hype up a crowd.

Williams also loved the phrase. After the shoot, he invited Benji to come to his studio and record. Williams wrote and recorded an electro-funk groove for him, and had his wife, singer Betty Wright, as well as Jeanette Williams, provide soulful backing vocals. With a heavy dose of robotic vocal processing that was cutting-edge at the time, Benji rapped and hyped his vocals like he was at the Inferno. A little slice of Miami’s dance culture was recorded that night. The song was called “Street Talk,” and it was released in 1983.

UK reissue label Emotional Rescue has just rereleased “Street Talk” and “Shoot It From The Hip.” The sleek and delicate funk jam also features KC & The Sunshine Band’s Robert Johnson on the drums and Eugene Timmons on the sax. Emotional Rescue has also re-released the 1982 track “Music Street,” a psychedelic robot-funk collaboration with Betty Wright that makes copious use of the vocoder. These three singles show Williams’s incredible range as an artist, but they also show how he was able to take the vibrant talent from Miami streets, clubs, and parks and document it. Miami in the early ‘80s was at a peculiar interregnum, in between the TK Records disco boom and the hip-hop explosion that would be known as Miami Bass. In this time in the early ’80s, much of the popular music in Miami was getting released by Williams on his two labels Tashamba and Konduko.

Vinyl

“He was a trendsetter,” says Benji. “He was a writer and he was an artist. He managed several groups around town. They were putting out 12-inches and 7-inches, that’s what was coming out of King Sporty’s studio.”

Originally from Kingston, Jamaica, Williams started out in reggae. He’s perhaps best known for co-writing the Bob Marley classic “Buffalo Soldier.” He moved to Miami in the early ’70s, and almost immediately started working with a broad range of artists, still bringing his own culture to the melting pot of Miami’s music scene.

In the mid-’80s, Miami Bass became the natural extension of the city’s diversity. There’s a famous anecdote that producer Amos Larkins II invented Miami Bass one night after partying all night with strippers, high on cocaine. He was so out of his mind that he accidentally blew out the bass on a track he produced. But the truth is more complex.

“When you asked how Miami Bass started, the answer could be many tentacles,” says music journalist Dave Tompkins, who is working on a book about Miami Bass. “The fast tempos are the convergence of Kraftwerk ‘Numbers’ and Afro-Caribbean percussion and Goombay celebrations. The answer might depend on the weather—with the mobile DJ scene and their migrating walls of speakers, by way of Jamaican sound systems, propagating low [frequency] parties outdoors. Or a studio moment in Fort Lauderdale like ‘Bass Rock Express,’ the first of endless ‘Bass’ titles. Or before that, the Amos Larkins 808 accident.”

Vinyl

The influence that reggae and Caribbean music had on Miami Bass can’t be understated. Reggae wasn’t a common influence among rappers in most cities in the ’80s, but it was in Miami. Williams was one of the artists that were laying the foundations for Miami Bass. Much of this music wasn’t overtly Caribbean-sounding, but his roots certainly informed his production choices. Williams would later go on to record some key Miami Bass tunes like Der Mer’s “Fall Out” (1984), Youth MC’s “Funky Fresh Beat” (1986), Classy III’s “Live & Let Die” (1985), and Smoove Matty Matt’s “Rappin Wrestling” (1986).

Aside from the work Williams did, his studio was a major hub for the music community, which helped to cross-pollinate the scene with people from different backgrounds. Everyone wanted to record there, from local talent to national touring acts and Williams always wanted to help them create their vision. He would provide advice to anyone in his studio, and for the young up and comers in Miami—like 2 Live Crew’s Luther Campbell—he would lend salient business advice.

“You could go to King Sporty’s house anytime, you’d see Bunny Wailer, Dennis Brown, George Clinton, all them right there at Sporty’s house in the studio,” says Benji. “He produced a lot of local artists. A lot of local beats came out of Sporty’s studio. In the ‘80s, you came through Sporty’s. Sporty was the person you needed to get in contact with to get put out internationally because he knew all of the record producers and promoters. That’s why they called him King Sporty.”