Thirty years after he passed away from a cardiac arrest, alone at the age of 49 in Buffalo, New York, the artistic legacy of minimalist composer Julius Eastman is stronger and more visible than ever. Following the important work done by Mary Jane Leach in her book Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and his Music, which pursues the faint trails Eastman left behind after his decline into homelessness and eventually death, more and more of Eastman’s scores and recordings have become readily available. His compositions, once rarely performed by ensembles that Eastman wasn’t in himself, are now commonly performed and studied. Eastman’s place in the canon is being continually re-appraised, his name now mentioned alongside giants of New York minimalism like Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and La Monte Young. The recent release of Femenine, a 1974 recording of a pivotal transitional piece in Eastman’s oeuvre which features the composer himself on piano, offers important clues to the way his forward-thinking vision developed between his earliest and latest periods.

Accomplished not only in composition, but musical performance, theatrical vocal, and dance, Eastman brought his individuality to every discipline he worked in. He never took vocal lessons, and taught himself musical notation; this natural knack for music—despite a lack of formal training—allowed him to study piano first at Ithaca College, then at the esteemed Curtis Institute of Music. As a performer, musician, and composer, Eastman was committed to a sense of self. In an introduction he gave to his concert at Northwestern University, he explained the title of Gay Guerrilla, and revealed a central pillar of his ideology:

“These names, either I glorify them or they glorify me. And in the case of guerrilla, that glorifies gay…A guerrilla is someone who in any case is sacrificing his life for a point of view. And you know if there is a cause, and if it is a great cause, those who belong to that cause, will sacrifice their blood because without blood there is no cause.”

This aggressive, front-facing philosophy was a core tenet of Eastman’s worldview, and it bled through in everything he did. Not satisfied with simply being himself, Eastman put his identity at the forefront of his work—to experience Julius Eastman is to know who he is. “What I am trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest,” he said in an interview with the Buffalo Evening News in 1976. “Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest.” To be Black and gay is to have your existence politicized in your daily life, so Eastman saw fit to bring those politics into the performance space and throw them back into the faces of people who might prefer to look away; if he doesn’t get any respite from being reminded of who he is, why should you?

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Eastman’s Femenine might appear on its face not to possess those guerrilla sensibilities of his later work—it is simpler, more traditionally “beautiful,” and less apparently antagonistic—but a closer look reveals that his DNA is all there. Performed at Composers Forum in Albany in 1974, this recording of the work was the only one known to exist upon its original release in 2016; more recordings have been created since—including a beautiful rendition by Anton Lukoszevieze’s ensemble Apartment House for Another Timbre—but this recording on Helsinki label Frozen Reeds is notable for being the only one featuring Eastman himself. Along with the composer on piano, various wind instruments are present—a marimba or vibraphone (nobody seems to remember which), electric bass, and a mechanized contraption that shook sleigh bells at a constant pulse. Based heavily upon a constant repeated phrase, with unique, skeletal scores for each performer laden with vague directions, Femenine has a very loose approach to compositional structure. Each performer’s score was said not to be synchronized with the others, doubtlessly owed to Eastman’s experience playing improvisational music with his brother Gerry, a jazz musician.

In another portion of his interview with the Buffalo Evening News, Eastman said of jazz—and particularly, of improvisation—that it is “exciting because it allows for instant expression of feelings,” and that “it comes closer than classical music to being pure, instantaneous thought…I feel as if I am trying to see myself.” Though Eastman’s stated goal with Femenine was to provide listeners with a pleasing, angelic experience—”should we say euphoria?” Mary Jane Leach quotes him saying in the liner notes of this release—the more implicit goal in everything he did was to offer up a piece of himself. Eastman saw the act of performing on his own compositions to be an expression of himself, saying in a column he penned titled The Composer as Weakling: “Today’s composer…has become totally isolated and self-absorbed…The composer must become the total musician. To be only a composer is not enough.”

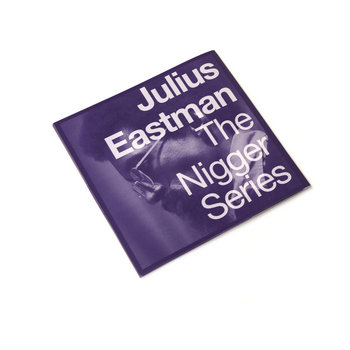

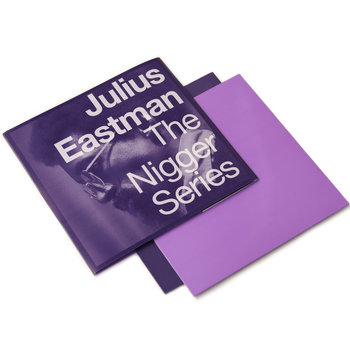

Though Femenine predates the more provocatively titled pieces in his 1980’s “N—r Series,” its peculiar spelling suggests, in a more subtle way, something else that was fundamental to who Eastman was: his flouting of gender norms. Attendees of the concert recall that he was wearing a dress during the performance. A currently lost companion piece, Masculine (1974), was known to occasionally be performed at the same time as Femenine in another section of the same venue, becoming experiences inextricably linked to one another and further suggesting a flirtation with challenging the gender binary.

2 x Vinyl LP

It’s easy to talk about Eastman’s quirks and his flamboyant personality when discussing his work, but perhaps what is most extraordinary about Eastman is also what is ordinary about him. It’s not extraordinary to be Black, to be gay, to want to create, or to want to be seen and understood; we should take caution to fold Eastman into the establishment of the avant-garde too quickly, lest we forget the ways he fought to rock the boat—the ways he had to rock the boat, by necessity. Eastman deserves to be part of the conversation when discussing the legacy of minimalism; not because he stood alongside those considered great, but because he stood alone—determined to be heard, but on his own terms.