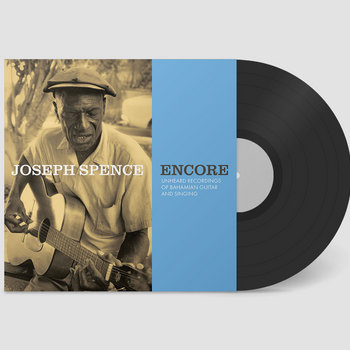

Photos by Guy Droussart, collage by Bandcamp

Photos by Guy Droussart, collage by Bandcamp

The guitarist and vocalist Joseph Spence was just 19 years old in late September of 1929, when a category four hurricane pummeled the Bahamas, inflicting catastrophic damage on the islands of Andros and New Providence. He decided to help with rescue efforts, retrieving the bodies of 27 sailors from a sponge-fishing schooner named Pretoria. The west coast of Andros was shallow, which made it inhospitable to ships but ideal for what was once a thriving local industry, sponge fishing. Locals, including Spencer, harvested natural sponges from the coral floor by diving from dinghies floating above. The shipwreck was immortalized in a song called “Run Come See Jerusalem” that was first recorded in 1958 on a trip to the islands by American folklorist Sam Charters.

On that version—released the following year on a Folkways Records collection entitled Music of the Bahamas Vol. 2: Anthems, Work Songs, and Ballads—singers Frederick McQueen, John Roberts, and Blake Alphonso Higgs offered a dazzling example of a Bahamian tradition known as “rhyming,” where a lead singer provides an improvisation-heavy narrative over earthy harmony vocals. The first volume of his recordings was devoted to the music of Joseph Spence, the first time his music was heard outside of the islands. In 1965 Peter K. Siegel, a 21-year old New Yorker immersed in the folk revival and deeply enamored of Spence’s music, took his own trip to the Bahamas with folksinger Jody Stetcher, to record traditional music from the islands, including a session with Spence recorded in the backyard of his sister Edith Pinder’s home.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“During a break, while I was changing reels, Spence and Edith started talking about [his] personal experience on the day of the shipwreck,” Siegel says. “They were talking about how he ran down to tried and rescue people that day. But he didn’t record the song. Later on, when Jody and I were at Spence’s house, we asked him if he could do the song. That’s the only song where I’ve heard Spence do—I don’t know if you’d call it “rhyming,” but he lines out the story. He does it in a different way. He does it in a narrative way, in the verses. I think part of that is because he’s reliving the experience. It had to be a very big thing for him”

That recording is among the highlights of Encore, a superb new collection of previously unreleased music Siegel taped that year in the Bahamas and in New York, during Spence’s first visit to the US. Compared with the earlier version recorded by Charters, the guitar-driven Spence performance is spiked with emotional accents—grunts, cries, and quavers—that suggest the lasting impression the experience left upon the singer, enhancing his already singular style with highly charged feelings. Spence died in 1984 at the age of 73, and nothing in the decades since has diminished his sound, a peculiar amalgam of gospel, blues, and calypso where his gruff, avuncular singing toggled between plaintive cries and non-verbal croaks, moans, and unexpected, deeply rhythmic outbursts. His sense of time was all his own, and his idiosyncratic performances could deftly interpolate a phrase from another song, or play with rhythm only to lock back into the original feel at the drop of a hat.

In the Bahamas, Spence remains largely unknown. “The Bahamas has been identified with lots of more popular music traditions, including traditions that don’t come from the Bahamas, like calypso,” explains Siegel. “There’s a lot of music that’s intended for tourists. Joseph Spence is still pretty unknown in the Bahamas.” Spence performed for friends, family, and colleagues, wiling away the hours, and until he was brought to the US by the Friends of Old Time Music in 1965—on a trip partly organized by American folk icon Pete Seeger—he had probably never given a formal concert like the ones he gave on that trip in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Siegel was a fledgling member of the organization, frequently recording its concert productions, many of which appeared on a 3-CD set released in 2006 that he produced with music by the likes of Dock Boggs, Bill Monroe, and Mississippi John Hurt. He was charged with hosting Spence on the New York visit, and he took his guest to the top of the Empire State Building. “Spence was a seeker of new perspectives,” says Siegel. “That comes through very much in his music. From the observatory at the top of the Empire State Building he had a view of the world he had never seen before. And he was wondrously enamored of it.” Following that visit, they headed to the 31st St. apartment where Siegel was living with his parents. A spontaneous recording session took place, and six of the tracks on the new album were taped at that time.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The experience in New York solidified Siegel’s desire to produce recordings of traditional music. “I was so impressed by the work of people like Ralph Rinzler, John Cohen, Mike Seeger, and Art Rosenbaum,” says Siegel. “I knew these guys. And they were all great musicians. And it was obvious that a part of their musical life was recording the people they had learned from and letting other people hear them. I just accepted that as what it meant to be in New York City playing traditional music. You would want people to hear the people you learn from. So I totally wanted to do that kind of recording.” Siegel was a member of a young folk ensemble called the Even Dozen Jug Band—whose fellow members included John Sebastian, Maria Muldaur, David Grisman, and Stefan Grossman, among others—and he befriended Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman during an audition, which led to a job at the label. Working with the great classical music producer Tracey Sterne, he helped to re-image the fledgling international branch of the subsidiary Nonesuch Records into Nonesuch Explorer Series, which became a crucial player in the elevation of global music into something outside of academia, particularly its groundbreaking recordings of Indian classical music and Indonesian gamelan. “It wasn’t academic,” Siegel says. “And it wasn’t presented as tourism, either.”

Yet Siegel’s experiences with and love for Spence’s music stand out. During the pandemic, he began poring through his tape archives and the unreleased Spence recordings electrified him. “I listened to all the old tapes of Joseph Spence and everything from the Bahamas,” he says. “And I was quite pleasantly surprised to see that there was some really great stuff there that had never come out before.” The music on Encore, which includes old pop songs like “The Glory of Love,” calypso classic “Brown Skin Girl,” and the American spiritual “Give Me That Old Time Religion,” reinforces Spence’s uniqueness, underlining the idiosyncrasies he brought to every performance. More than half a century later it still sounds like nothing else in the world.