A screen from Sword & Sworcery

Jim Guthrie has played video games since he was a kid, but he doesn’t really consider himself a gamer. He’s spent most of his adult life as a touring musician, playing with indie rock bands like Islands and Human Highway. One of his solo albums, Now More Than Ever, was even nominated for a Juno—Canada’s version of the Grammys—in 2005 (it lost to Feist’s Let it Die). Despite his critical success and indie rock street cred, he lived in a house in Toronto with five other guys, touring sporadically, and making something in the neighborhood of $12,000 a year. “I wouldn’t say I struggled, because I was doing what I wanted to do,” he says from his home studio, where he’s surrounded by keyboards and recording tools. “But I wasn’t the best planner.”

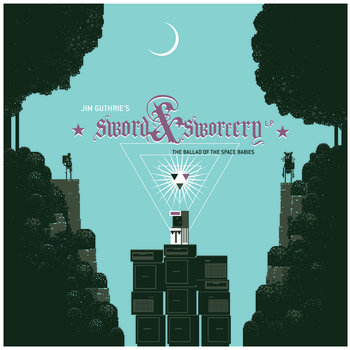

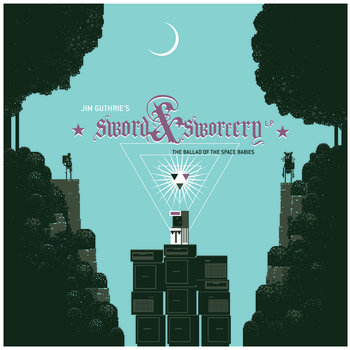

Then, in 2005, he got a postcard from a longtime fan and budding game designer named Craig Adams. In return, a flattered Guthrie sent Adams a burned CD loaded with songs he’d built using the strangely feature-rich Playstation game/sound-tool, MTV Music Generator. “This was a huge moment in Superbrothers history,” Adams recalls. “Listening on headphones, every song suggested some visual treatment.” This exchange kicked off a collaboration between the pair that produced the 2011 iOS game, Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP.

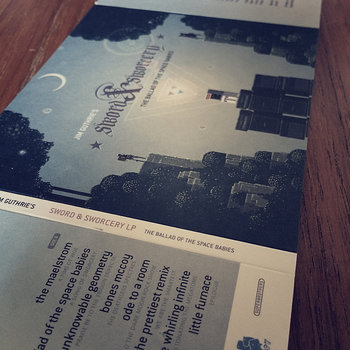

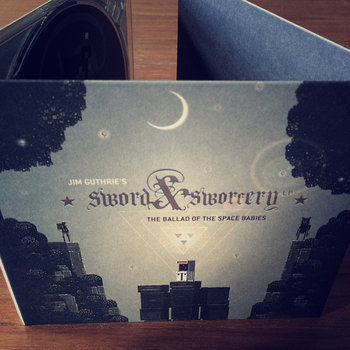

Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Apparel, Cassette, Vinyl LP

The game’s developer, Capybara, paid Guthrie a few thousand dollars up front to compose the soundtrack, with the stipulation that he’d own the music once the game was released. It felt like a gamble. “At the time, I was signing up to own music that no one might ever buy, and own points on a game that might never sell,” he says now. “It wasn’t a slam dunk.”

But the game got rave reviews from both the gaming and mainstream press.

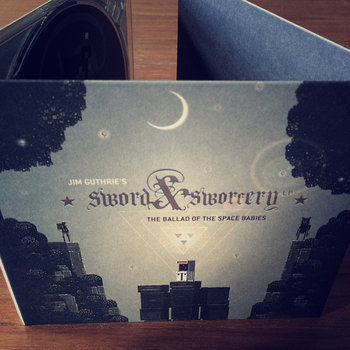

The early response was positive enough that Guthrie pressed 500 vinyl copies of the soundtrack to sell on Bandcamp. Two weeks after the iPad release—while positive press was still flooding in—Guthrie put the album online. He added yet another subtitle, The Ballad of the Space Babies, to an album name that was already a mouthful. He mentioned it to his thousand-odd followers on Twitter. And then his life changed.

“Every time you sell something on Bandcamp, you get a little email,” he says. “And it was just, like, fire. Hundreds of them. It was like a scene in a movie. I was just staring at my phone saying, ‘What the hell?’ I thought there was a weird email-feedback-loop going on.” The digital sales quickly numbered in the thousands. His vinyl pre-order copies were gone within the first week, and an additional batch of 500 LPs he ordered shortly thereafter sold out within a few days. In Guthrie’s relatively humble indie rock world, this seemed like madness.

Guthrie estimates that he’s sold well over 30,000 digital copies of his soundtrack (in addition to copies that were packaged with the game when it was released on PC and Mac), and over 5,000 copies on vinyl.

“It has sold more than all my other stuff put together,” he says. “It let me put a down payment on my house. It changed things in a big way, to where I kind of feel like an adult now.”

Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Apparel, Cassette, Vinyl LP

In the five years since Sword & Sworcery’s release, Guthrie has become a sought-after video game composer. He’s currently wrapping up work on Below, the second Capybara title since Sword & Sworcery, and he’s barely toured since 2011. “I sort of hated being stared at onstage for an hour while I made all these funny guitar faces and tried to get through a song,” he admits. “It’s actually been kind of a welcome change for me. I get to stay home and be with my wife and pet my cat and make music—and I still get paid at the end of the day.”

The gaming industry’s raw numbers are eye-popping, but they don’t do a lot to illuminate Guthrie’s success story. Last year, worldwide digital gaming revenue hit a record $61 billion. It’s an almost inconceivable number, and it puts a game like Sword & Sworcery into perspective. In its first two years, the game sold 1.5 million copies. Last year’s top digital title, the popular “free-to-play” mobile game, Clash of Clans, grossed over $1.3 billion in 2015 alone. Its developer, Supercell, claims that over 100 million people play its titles every day. Yet, asking a Clash of Clans player who makes the game’s MIDI-driven classical music would be like asking a Vegas high-roller who soundtracks their favorite slot machines. The question is beside the game’s addictive point. Clash of Clans’ own in-game credits don’t mention music, and inquiries about the soundtrack on the developer’s message boards have gone unanswered.

But on the artful edge of indie gaming, where Guthrie has found a niche, music is often indispensable. The musicians who specialize in soundtracking some of the medium’s most groundbreaking titles have gained cult followings, and some are becoming full-blown stars. On Bandcamp, soundtracks for games like Undertale and webcomics like Homestuck, have remained near the top of the sales charts for months on end.

And yet to the larger music industry, video game music still seems to be a mystery. While boutique labels like LA’s iam8bit and London-based Data Discs have found success in creating limited-edition vinyl pressings of retro and indie game soundtracks (many of them drop-dead gorgeous), and Ghostly released C418’s soundtrack for Minecraft on vinyl last year, most of the larger indie labels in the U.S. have yet to jump on the game soundtrack bandwagon.

There is one label that’s seizing the opportunity: Ghost Ramp, a Los Angeles-based imprint started in 2008 by musician/entrepreneurs Nathan Williams and Patrick McDermott. The label made their first foray into game soundtracks earlier this year, when they released a 7-inch vinyl soundtrack for a stunning-looking, ’80s-inspired racing title-in-development called Drift Stage. (In truth, it’s more like a 10-and-a-half-inch: it’s shaped like one of the game’s boxy, Miami Vice-colored race cars.) Over the course of the next year, Ghost Ramp will release soundtracks for the dungeon-crawling game Crypt of the Necro Dancer, the severely dystopian Lisa: The Painful RPG, the post-apocalyptic twin-stick-shooter Nuclear Throne, and Nina Freeman’s experimental (and semi-autobiographical) coming-of-age game, Cibele.

Williams and McDermott are both self-described gamers, but they’re also underground music tastemakers in a position to legitimize game soundtracks for music nerds. Williams, who is best known for his band Wavves, also plays in a psychedelic, 8bit-influenced side project called Sweet Valley with his brother Kynan. For Ghost Ramp, the prospect of being involved with games on any level was exciting. But when they began to reach out to developers and musicians to investigate the popularity of game soundtracks, they were shocked by what they found.

“I mean, we knew these games were popular,” McDermott says. “But we didn’t know the hard numbers. When we first reached out to Danny Baranowsky, from Crypt of the NecroDancer, he told us he had sold 23,000 copies of the music from the game. In the indie music world, that would be astronomical. That would be like signing Beach House or something. But no one knows who Danny is in the traditional music world.”

For McDermott, releasing game soundtracks on vinyl isn’t all about getting the music on a superior format. “I don’t own a record player,” he admits sheepishly. “For me, the vinyl is just a vessel for a really great, cohesive art piece.”

As it turns out, creating that art piece is a lot of fun, especially because video game musicians tend to be easy to work with. “It’s such an amazingly less jaded and less ego-ridden community than the music business at large,” McDermott says. “Talking to these people is an exciting, fun thing.” One artist McDermott talked to, who politely declined signing to Ghost Ramp in favor of an eventual self-release, struck a chord. “His game had just sold 500,000 copies in its first month. And he was so great.”

That musician’s name was Chris Remo. His decidedly warm soundtracks for two of the most empathetic indie games of their generation—Gone Home and Firewatch—haven’t had the explosive success of other titles, but he says they’ve helped him buy new instruments and make rent in prohibitively expensive San Francisco. The income has also helped him build the upstart game company behind Firewatch, Campo Santo. Remo, who co-founded the gaming podcast network Idle Thumbs and has worked in just about every facet of indie games, says that there’s a reason indie game soundtracks tend to be more adventurous than their big-studio counterparts.

“The music is often the last thing [developers] consider,” Remo says. “You spend a lot of time thinking about how it looks, because you have to sell it in screen shots and trailers. You, rightly, spend a lot of time thinking about how games play.” For major game releases, Remo says that kind of thinking results in big, orchestral scores that often feel safe, or downright cliché. Necessity, though, is the mother of invention. “The place you’re most likely to get something interesting is on a really small scale. That’s where one person can make a really huge difference—because they’re probably the entire music department.”

They’re also likely to be gamers themselves. Perhaps as a result, indie game soundtrack artists often acknowledge gaming’s bleepy-bloopy music history in a way that major studios don’t.

Matthew Thompson, a lecturer of music at the University of Michigan who teaches classes on game music, tends to focus on games from the ’90s and ’2000s in his research, but his students recently turned him on to Undertale. The game was a huge breakout hit last year—one that the website Steamspy estimates is owned by somewhere around 1.5 million users (Fox also sells the game directly to fans). Thompson says he has been “taking notes” on his first playthrough, and says that while the game’s music is minimal and nostalgic, “there’s also something new about it. That’s what we all want from music, though, right? Familiar enough that you accept it and connect with it, yet just different enough that it makes you want to hear it.”

Toby Fox, who designed and developed Undertale while also writing and recording the music using free soundfonts and synths that he found online, says the success of his soundtrack is “definitely a nice surprise.” Fox, who counts composers like Yasunori Mitsuda (Chrono Trigger) and Hiroki Kikuta (Secret of Mana) among his many game-world influences, says that the last time he checked, about 12 percent of people who played Undertale have also bought the soundtrack. “That’s an unusually high number,” he admits.

Fox is practical in addressing the current popularity of indie game music. “Game soundtracks are popular partially because they remind the audience of an experience they liked,” he says. “That’s the required factor, along with the composition itself. If there wasn’t a game, its audience would be a lot smaller. I can’t think of many game soundtracks that are popular purely on their own merits, outside of hobbyists.”

Rich Vreeland may be an exception to that rule. Vreeland, who recorded a number of game and animated film soundtracks under the name Disasterpeace before finding widespread acclaim for soundtracking the gorgeous 2012 meta-platformer Fez, discovered internet message boards like 8bit Collective and The Shizz—both associated with chiptune, music made using retro game sounds—while he was studying music at the Berklee College of Music.

The chip music he found there informed the work Vreeland did on various game soundtracks as well as his own, game-inspired early albums, but he was never a purist—in fact, he says, he made almost all of his early music using GarageBand synthesizers. But eventually, that influence led to his widely acclaimed work on Fez, where his involvement went beyond just composing songs. He was an active participant in building the game—he refers to his role as “experience designer”—and his masterful, glitched-out ambient soundscapes blend so seamlessly with the game that it can be hard to tell where the visuals stop and the music begins. “It was the perfect project at the perfect time,” he says. “A lot of times when you work for hire, you’re trying to mold yourself to fit the needs of someone else’s project. But for Fez, I didn’t have to do that at all.”

Vreeland has gone on to soundtrack films (including the sleeper horror hit It Follows) and higher-profile games (Hyper Light Drifter being the latest), and he credits Fez for putting him on the map. “I haven’t had to look for work since then, and that was like five years ago.”

Soundtracks for games like Fez and Spelunky nod gently toward the console and PC gaming sounds of yesteryear, but some game soundtracks are actually built using that old technology.

When she was 7, Irish musician Niamh Houston spent her Holy Communion money on a Game Boy Color and a copy of Pokémon Blue. “It was the best,” she says. “I just loved the sound of the Game Boy.” By the time she was 16, Houston was building songs with the aftermarket Game Boy music tool LSDJ, and playing her first shows as a chiptune musician. She now goes by Chipzel. In 2012, Irish game designer Terry Cavanagh—consistently among the most inventive auteurs in indie games—asked to use her song “Courtesy” for Hexagon, a devilishly intense puzzle game he’d built at a game jam. The pair’s collaboration expanded as Cavanagh built an iOS version of the game, Super Hexagon, which sold around 50,000 copies in its first two weeks.

Houston gets a kick out of soundtracking so many gamers’ Super Hexagon frustration, but the coolest reward was seeing her soundtrack released on vinyl on the iam8bit label. A total of 1,600 copies were printed, and a rep from iam8bit says via email that there’s only a handful left. “I always wanted to get vinyl made, but it’s very expensive and you can never judge what the demand is going to be,” Houston says. The irony of recording music on a pocket-sized digital instrument and reverse engineering it onto one of music’s oldest formats is not lost on her. “It’s a strange lineage. It doesn’t seem like something that should happen,” she admits. “But it’s really cool.”

A vinyl pressing hasn’t happened for Undertale, though it would almost certainly sell. Toby Fox has kept the game’s merchandising at a minimum, and only recently added a “merch” page to the Undertale website. It initially scanned as sort of a righteous stand against consumerism run amok. His explanation was far more practical: “It’s way easier to avoid doing that, because Undertale has been so successful by itself. But my level of success is extremely rare. So if other devs want to make their lives easier by selling, like, collectible game-themed soaps, let’s not judge them.”

It’s an important acknowledgment, especially with more and more developers entering the field in the hopes of creating the next Undertale, Sword & Sworcery, or Gone Home. There was a time when the quickest route to making a huge impact on pop culture was by putting out a great album. Increasingly, video games are transcending to the level of great art—escapist, political, emotional, and subversive games abound. It’s a medium where experimentation isn’t just encouraged, it’s an absolute necessity. Caring about the medium means wanting it to keep mutating and growing into something new and unexpected. Maybe that’s why something comparably arcane, like an indie game soundtrack on vinyl, still holds so much allure. The games themselves are strings of code, but their physical soundtracks are tangible evidence that we were there when this art form was unfolding in startling new ways. We were rooting for an entire medium to grow up with us—to get smarter and better and more radical; to produce luminaries and legends. And we bought the collectible soaps to prove it.

—Casey Jarman