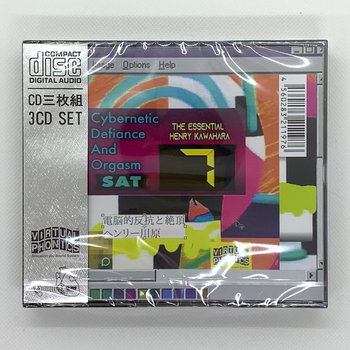

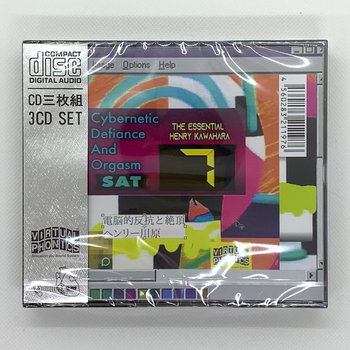

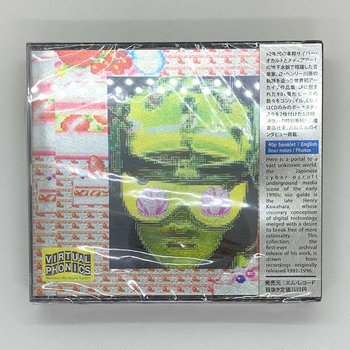

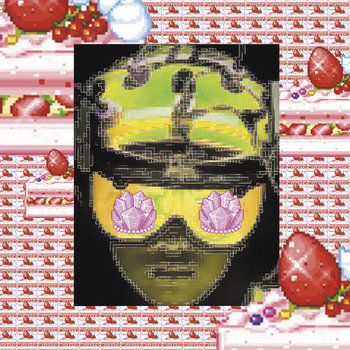

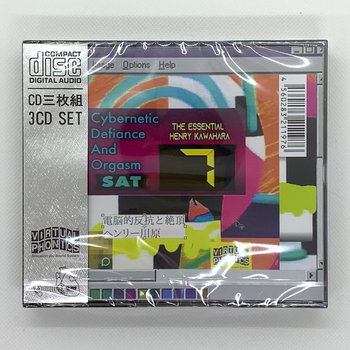

“Unlike other ‘new age’ CDs that are all about healing and relaxation, Henry Kawahara’s working concept was about the altered states and cybernetics caused by drugs, and the sound is unlike anything else on other releases from that time,” says music journalist Yuji Shibasaki, who wrote a profile on EM Records‘s latest compilation Cybernetic Defiance and Orgasm: The Essential Henry Kawahara for the Japanese publication TURN last July.

Born Yoshifumi Kawahara in the Western city of Fukuoka, the artist who eventually took Henry on as his stage name grew up in Japan during a time when the country was experiencing an occult boom of sorts. “From my personal experience in the late ‘70s, occult material was invading magazines, books, manga, art, and all other forms of mass media,” says EM Records label owner Koki Emura. In the West, the term “occult” usually refers to the paranormal; the Japanese version was more concerned with—as Emura writes in the compilation’s liner notes—“the sense of things hidden or secret, beyond ‘common sense’ and rationalism.”

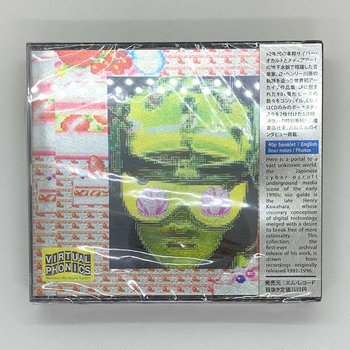

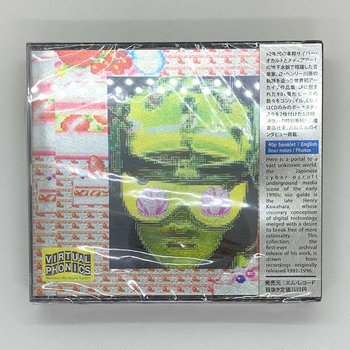

Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

Helping propagate this idea was Sugen Takeda, the owner of Hachiman Publishing, one of the premier sources for occult literature from the 1980s onwards. In an essay referenced in Emura’s notes, Takeda says, “the occult is a form of counterculture based on profound criticisms and questioning of Western rationalism which sprang from people who had witnessed or experienced the death of the so-called ‘grand narrative.’”

Just as important, though, was the fact that Hachiman Publishing had acquired the trademark and license to sell the 3D acoustic technology called Holophonics in Japan. Created by Hugo Zuccarelli in 1980, Holophonics captured life-like recordings bordering on the unsettling when you listened to it through headphones. Think of it like ASMR, but more likely to unnerve than relax.

At some point, Kawahara came across a Holophonics cassette, and would eventually contact Takeda. He told Hachiman’s owner that he had started experimenting with his own 3D recordings. Takeda already had a sense that sound would play a large role in his business moving ahead, and was also observing how the then-fledgling internet was offering the same kind of transcendental opportunity that the occult offered. That sparked the idea of the “cyber-occult,” which blended supernatural spirituality with futuristic technology. Hachiman began releasing music utilizing the new technology, including Kawahara’s own 3D sound system, as a way to help listeners go beyond the rational. Most of this “cyber-occult” music could only be bought in bookstores or through mail-order services, and they were categorized with ISBN codes typically used for books. This partially explains why Kawahara and the “cyber-occult” has existed in obscurity—music fans couldn’t find it.

Kawahara’s music exemplified this underground scene. His work wasn’t designed to simply drift into the background. Instead, Kawahara wanted to draw specific reactions from the brain, like replicating brain wave patterns during sex on Sound LSD: Subliminal Sex (the album notes indicate that the producer was mentally affected by the music). The album titles spelled out their aims: Out Of Body Experience, Fantasy Enhancer, The Sound Of Illusions. At the same time Kawahara was releasing these CDs, he was also working with fellow artist Keisuke Oki as Digital Therapy Institute to create the Brainwave Rider.

Emura first reached out to Kawahara about 10 years ago in an effort to archive his music. He remembers Kawahara (then living in Cambodia) being hesitant to the project at first, but he was swayed by Emura’s vision nonetheless; their relationship established, the two began mapping out what would become Cybernetic Defiance. Then, sadly, Kawahara passed away in 2012.

“The most horrifying practice of record companies is the ‘memorial release,’ where death is converted into commercialism,” Emura says. He wanted Kawahara’s music to be in the spotlight on its own merits, without a cloud of sadness hanging above it. As a result, the compilation wasn’t released until now, nearly a decade after his death.

Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

Because Kawahara passed before Emura could interview him, the artist’s process remains shrouded in mystery. So Emura found another angle through which to contextualize the music, framing Kawahara’s unique sound through the lens of Japan’s cultural ecosystem in the late ’80s and early ’90s. The liner notes for Cybernetic Defiance touch on the trends in spirituality and technology that were happening concurrent to Kawahara’s output. (Emura also published a deep dive into this time period, written in Japanese.) The atmosphere that fostered Kawahara’s electronic music is vital, elevating it above just being another “obscure” example of Japanese ambient, or somehow adjacent to the Pure Moods brand of “new age” music.

On Cybernetic Defiance, sonic elements criss-cross audio channels, and Holophonic recordings of water, voices, and dolphins creep into Kawahara’s music. “Sound LSD #.SS05/7.83HZ (Radio Mix)” swirls together electronics and disembodied vocal samples, while the mix of “Children In The Museum” included here creates an unsettling environment out of clanging bells. Where other new age or healing music from the time was softer and more restorative, Kawahara often explored the darker side of this realm. “But he also could make music like Steven Halpern,” says Emura. “It could feel schizophrenic.”

Part of Cybernetic Defiance’s success lays in showcasing how often Kawahara modified his sound over time. “Destination Of Endorphins” comes from a dolphin-centric mid-‘90s release Kawahara designed for the Stargazer, a “brain machine” Kawahara helped make for Hachiman. Even without the LED-blinking device, the track shows the playful side of Kawahara’s sound design. Then there’s the stretch in the middle of the compilation that highlights his interest in Southeast Asia, a recurring theme in his original work reminiscent of Haruomi Hosono’s experiments in reverse exotica in the 1970s.

“The music can be beautiful, but there’s lots of melodies where you aren’t sure which country or tribe it originates from,” Emura says. “The border is ambiguous, unstable, unnatural, and spooky at the same time.” He thinks this is one of the things that sets Kawahara apart from American artist Jon Hassell, to whom the Japanese artist is often compared. Hassell developed a sonic fantasy world with elements of Asian music, but he comes from a strong Western background. Kawahara, meanwhile, existed in the world he was creating, and rather than treat it as exotic, he could approach it from a more detached place. “His fictional world is unstable and uncomfortable.” The closest point of comparison, he says, would be the legendary visual artist Takashi Murakami, whose animated works similarly reject Western conventions in pursuit of the surreal.

Kawahara stepped away from music in 1996 for reasons that remain unclear, though Emura is on the case: as of this writing, he’s working on an in-depth essay looking at the environment that prompted Kawahara to stop creating. Cybernetic Defiance is by no means a definitive chronicle of Kawahara’s artistry or legacy, which will most likely remain shrouded in mystery for years to come. Emura plays up this lack of closure in conversation, teasing, “This compilation has a big secret I’ve never told anyone. One day, I’ll reveal it. Please listen again and again until then.” The open-endedness serves as an invitation to explore a moment in Japanese pop culture long overlooked, and thanks to Kawahara, a gateway to the beyond.