A video shows a group of friends—young men, their faces lit up by phone light and off-camera glow of a campfire. They’re smiling, at ease with both the camera and the instruments they hold in their hands. One of them, cross-legged and barefoot, cradles the unmistakable form of a banjo on his lap. As he plucks at the strings with a certain absence of attention born of skill earned through years of practice, he closes his eyes, inclines his head and begins to sing a plaintive, mournful song.

The banjo player is Hassan Wargui and the video, which appears on Wargui’s Facebook page, is shot not in Appalachia, but in a cave in the Sous valley, a region in the southwestern corner of Morocco, perched between the mountains of the Anti-Atlas immediately to the east and the Atlantic ocean to the west. It’s a fertile part of Morocco, most famous for the oil produced from the fruit of Argan trees and the goats who sometimes climb them.

“I love the banjo, it’s my first instrument,“ says Wargui. His music is actually part of a hidden tradition of banjo music in the area that dates back to the 1970s: he learned to play by imitating groups like Archach and Izenzaren, who hold a legendary status in the Sous. “No one taught me, I learnt myself.”

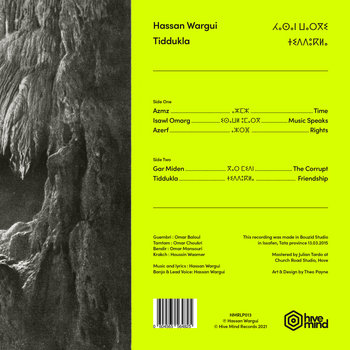

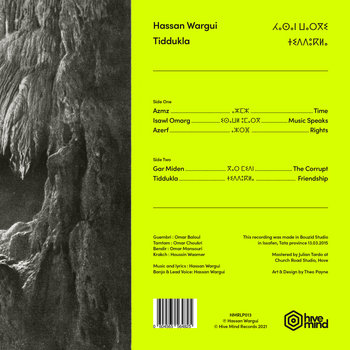

Vinyl LP

The modern banjo arrived in Morocco in the ‘50s, when the country was still occupied by the French after World War II. Political scientist Hisham Aidi suggests in his book Rebel Music: Race, Empire and the New Muslim Youth Culture that American GIs stationed in Morocco traded banjos for cigarettes with the local population. In the 1970s, the banjo-wielding Nass El Ghiwane shot to fame (they’re still probably the most popular group in Morocco), bringing together Moroccan and Western music with revolutionary social commentary.

Moroccan musicians were likely drawn to the banjo because of its similarity to the guimbri, a stringed instrument with a camel skin membrane that provides the hypnotic rhythms for gnawa ceremonies. Gnawa was created in Morocco by enslaved peoples from Sub-Saharan Africa who merged their music and traditions with the principles of Sufi Islam, and the guimbri clearly resembles the ngoni, an instrument found throughout Mali. There’s a parallel relationship between the Western banjo and West Africa, which evolved from stringed instruments brought to North America, unintended collateral of the slave trade. Coincidentally, both the Anti-Atlas and the Appalachian mountains were once part of the same mountain range over 335 million years ago.

There’s another practical explanation for why the banjo has spread through Morocco, says Marc Teare, who’s just released a record from Wargui’s group Tiddukla on his label, Hivemind. “It’s a noisy instrument,” he says, meaning it can be played as part of a group, without the need for amplification. “You can have a banjo and a group of percussionists, and the banjo is not struggling to make itself heard.”

Yet the groups who inspired Wargui struggled to make themselves heard for a different reason. Archach and Izenzaren were Amazigh (sometimes referred to as Berber, from ancient Greek for barbarian), part of a minority who comprise 35-40% of Morocco’s population. The Moroccan state pursued a policy of Arabization after becoming independent from France in 1956, and Amazigh culture was suppressed. The speaking of Amazigh languages (principally Tachelhit in the south west, where Wargui lives, and Tamazight in the Central Atlas) was even banned. In the 1970s, when the fiercely Amazigh Izenzeran began playing, singing in Tachelhit could even land you in jail, Teare says. The times have changed, of course, and Tamazight has been taught in schools since 2003. It’s still challenging to make a name for yourself as an Amazigh musician though. Wargui doesn’t pull punches: “As Amazigh, we have few concerts, and we experience racism.”

Any money that Wargui makes from music comes from Amazigh festivals, performances at weddings and religious festivities. “From recordings, it’s really nothing,” he says. Making money from music alone is impossible: He regularly travels from his village, Issafen, to Morocco’s second largest city, Casablanca, where he finds work selling food. His experience is typical of many who live in Amazigh regions, rural areas which suffer from higher levels of poverty than the rest of the country. “The village is beautiful and it’s very nice to live here, but the problem is there is no work, no jobs, and no money.”

Vinyl LP

Wargui could be forgiven for giving up music entirely, yet a steady stream of recordings and live videos have continued to appear on both his YouTube and Facebook pages over the years. It was via Wargui’s YouTube channel that Teare came across Tiddukla (‘friendship’ in Tachelhit), which Hassan had uploaded in 2015. Teare has spent many years visiting Morocco, indulging his passion for the country’s music (before starting Hivemind, he uploaded tapes he bought in the country to his blog, Snap, Crackle and Pop) and he marvels at Wargui’s drive when it comes to producing music. He likens it to a calling: “If he doesn’t have a group around, people to play with, then he’ll do it all himself on FruityLoops”.

Teare isn’t the first person from outside Morocco to fall under the spell of Wargui’s music and personality. Jace Clayton, the artist and writer known as DJ /rupture, stumbled upon another of Wargui’s groups, Imanaren, after hearing the music booming from a sportswear shop in a Casablanca around 2009. He was so struck by what he heard that, with the help of a Moroccan friend, he called the number on the back of the homemade CD to get in touch. (Wargui’s cousin answered, and immediately hung up as he thought it was a joke). Clayton would go on to re-release the group’s music on his label, Dutty Artz, and the pair collaborated for a series of live shows in Morocco and Tunisia, including one with Clayton’s group Nettle.

One thing that makes Wargui so unique is that he writes his own songs instead of pulling from traditional repertoires. “I think I have 154 songs,” he says. “I like to write songs when I travel, when I go to the mountains.” Being in these places helps him to “flashback” and focus on material for his lyrics, he explains. The subject matter varies from well-trodden subjects like love and romance to what he describes as “social reality, life in Morocco, the poor, and humanity.” Sometimes he even writes stories based on his friends, who frequently pester him to write songs about them. “But I don’t tell them, I just write and keep it to myself.”

Even if you’re unable to understand the lyrics, Wargui’s music has a startling universality to it. On Tiddukla, there’s an easiness to how his voice rises and falls; a harmonious tranquility to how his banjo slots into the pitch and yaw of the rhythms, between the low hum of the guimbri and gentle chatter of hand drums and percussion. It’s by turns longing and hopeful, laced with a latent emotion that doesn’t require translation. This openness may come from its creator’s intent, says Teare. “Hassan wants people to hear his music. He wants to broaden his audience.”