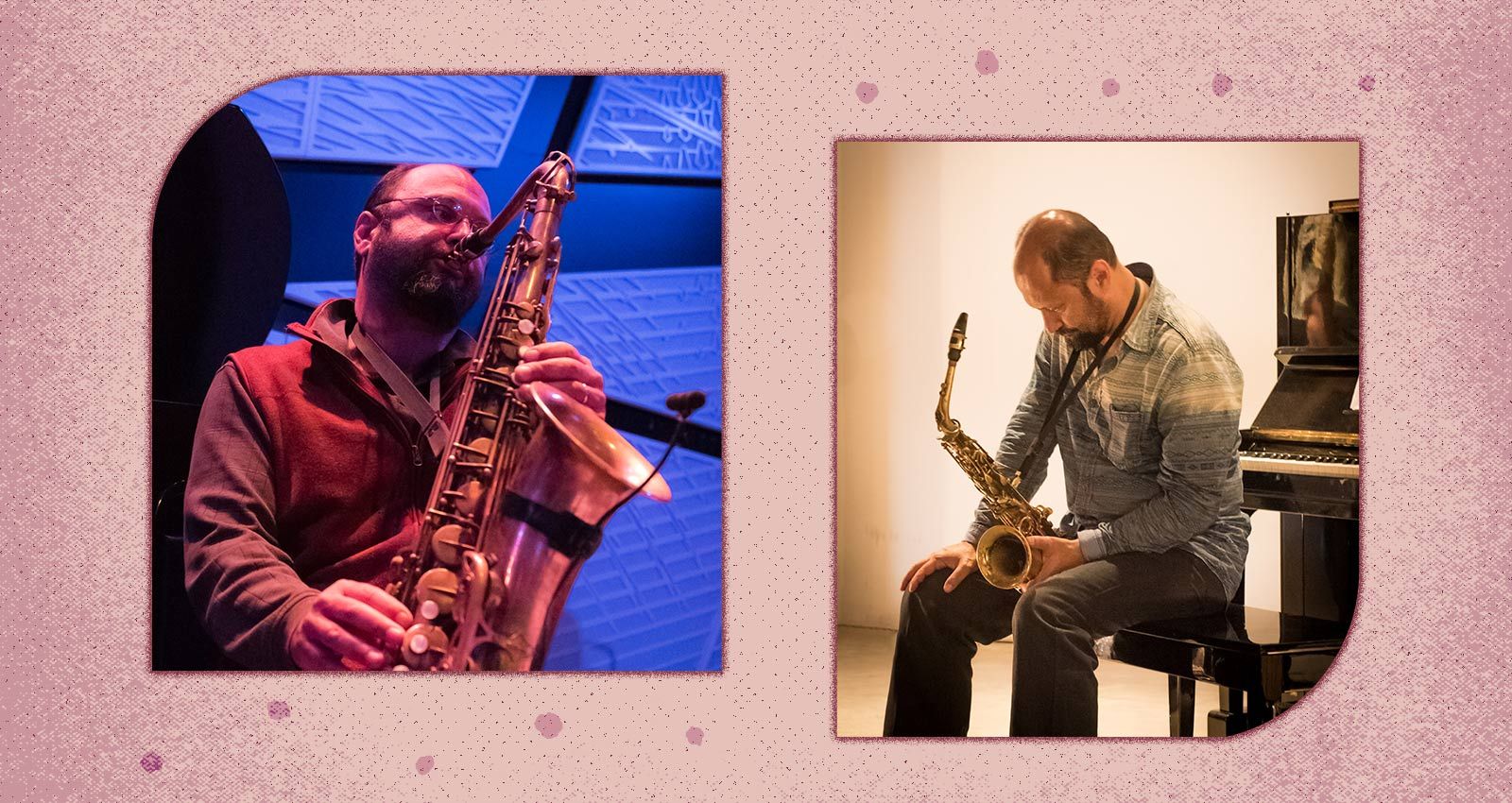

Photos by Jill Steinberg

Photos by Jill Steinberg

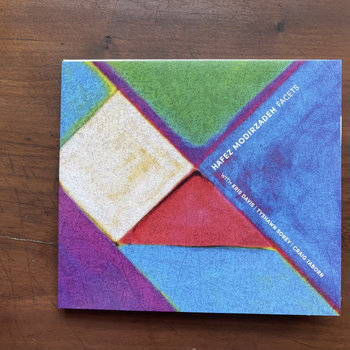

Iranian-American saxophonist Hafez Modirzadeh has spent decades straddling two traditions, finding the commonalities, and using them to create something entirely new. Born in Durham, North Carolina to an Iranian father and an Irish/Russian mother, he came to jazz as a teenager, enraptured by Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, and Lester Young. “It wasn’t until I had to consciously consider who I was in this society and as a musician,” he says, that he was drawn to Persian music, despite having heard his father sing and play the tombak (a type of drum) at home. Living in the Bay Area, he began studying with a traditional Persian musician, Mahmoud Zoufonoun, and soon perceived similarities between the two approaches to making music.

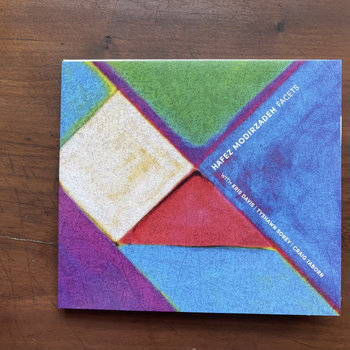

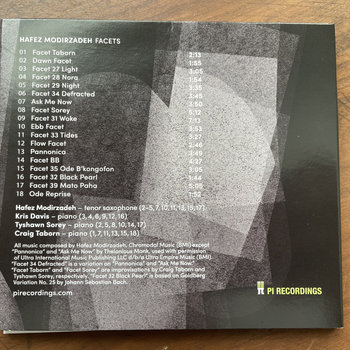

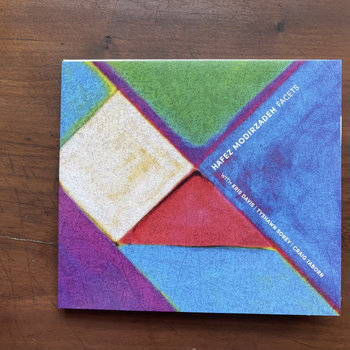

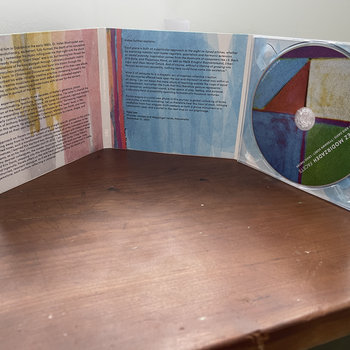

Compact Disc (CD)

“What’s in common between the two is a variation on a model,” he says. “You have a model, like we have standards in jazz, and then we vary those models… In Persian music it’s sort of the same, you have these model melodies and formulas and forms that are part of the repertoire that you’re taught. That repertoire is called the radif, and then after you get familiar with your teacher—it’s also oral tradition, that’s another common denominator—you begin to create and variate on the model.”

By combining Persian overtones and harmonies with jazz structures, Modirzadeh started formalizing his own musical system, which he dubbed ‘chromodality,’ while studying at Wesleyan University. (Anthony Braxton was on his dissertation committee.) He worked on it throughout the 1990s and early 2000s on a series of independent releases, then signed with Pi Recordings for 2012’s Post-Chromodal Out!, a collection of 27, mostly short, linked pieces performed by trumpeter Amir El-Saffar, pianist Vijay Iyer, bassist Ken Filiano, and drummer Royal Hartigan, plus a few guests. The music swings at times, but lurches sideways at others, and while the harmonies between the horns aren’t “Persian” in any clichéd way, they have a keening quality that nods to Middle Eastern music while also drawing on the sharp-edged interplay between Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry in 1959.

His second Pi release, 2014’s In Convergence Liberation, is even more unclassifiable. It features the Ethel String Quartet, three Middle Eastern musicians (El-Saffar on trumpet and santur; Amir Abbas Etemadzadeh on bells, daf, doholla, and tombak; and Faraz Minooei on santur), and vocalist Mili Bermejo, interpreting the poetry of Rumi in Spanish. In the middle of all that, Modirzadeh inserted post-bop saxophone solos. According to him, “the idea was not to get pinned down” by categories like “jazz,” “classical,” or “folkloric” music. The result is a fascinating blend of ideas that could appeal to fans of Cherry, flutist Nicole Mitchell, or avant-garde chamber music.

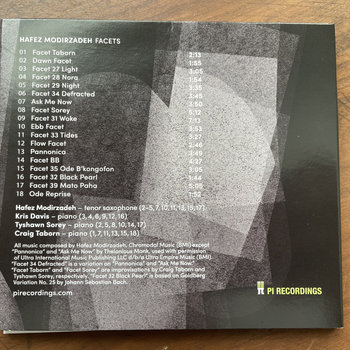

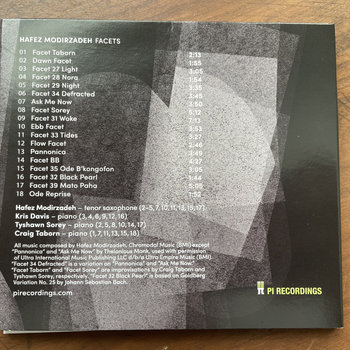

The music on Modirzadeh’s new album, Facets, has been gestating for several years. It was initially presented at New York’s Jazz Gallery in November 2018, under the name The Pulsivity/Resonance Project. Over the course of four sets, Modirzadeh and pianists Leo Genovese, Peter Apfelbaum, Diane Moser, and Tyshawn Sorey performed versions of the same set of compositions, all based around a uniquely tempered scale.

Compact Disc (CD)

Eight notes, covering roughly an octave and a half in the upper-middle register of the piano’s range, were slightly retuned. “Just tweaked slightly low,” he explains. “This has been a collaboration with piano technicians who at first were very reluctant to go outside tuning the piano the way it was intended. But what is intended, you know? Was the piano intended to be played the way Cecil Taylor played it, or Monk, or Don Pullen?”

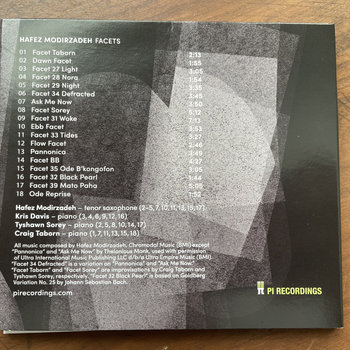

The album features three pianists —Sorey, Kris Davis, and Craig Taborn—tackling these pieces, along with interpretations of Thelonious Monk compositions including “Ask Me Now” and “Pannonica.” The result is both captivating and unsettling. The melodies, even when familiar, feel not-quite-right, as though the players, saxophonist and pianist alike, are finding their way through in real time. The slightly bent pitches register not as “out of tune” but haunted, disintegrating, or heard from underwater, and notes seem to take longer than usual to decay.

Part of Modirzadeh’s goal with Facets, and with chromodality as a whole, is to break the grip of what he calls “chromatic hegemony,” the idea that music must be composed using the twelve-note Western chromatic scale. He says, “Sure, [jazz is] an indigenous American music, born here in the West and it’s certainly understood inside of a white racial frame of chromatic supremacy. However, these other tones that were not coming from the West, that were not part of that chromatic spectrum, I knew inherently they have a place…together.”

One way he emphasized the deliberateness of his choices was by insisting on the proper names for the pitches. “In Iran they don’t call them quarter tones. They have a name…these Persian tones are called koron, for a half flat, and sori, for half sharp. And I said to the musicians, stop talking about quarter tones and start talking about koron and sori, if you’re gonna talk about this music, because that’s what informed it.”

Davis, Sorey, and Taborn were sent the scores in advance, but their first encounters with the re-tuned piano came in the studio, on the day. “This is to their credit, they didn’t just walk away and say, that’s out of tune,” he says. “You don’t know how many musicians did that over the years. But they sat down, all three of them separately, with reverence. Because they respect the instrument, they respect the possibilities that could happen from that sound.” The result is startling—but only for a moment. By the time Facets is over, Modirzadeh’s harmonic concepts feel perfectly natural. Which is the whole idea.