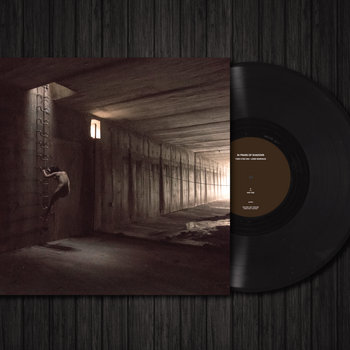

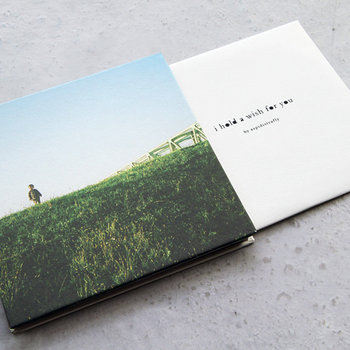

Last year, the Singaporean musician Yuen Chee Wai and his Norwegian collaborator Lasse Marhaug released In Praise of Shadows, an album that was more than 10 years in the making. An enveloping soundscape of drones and glitches, In Praise of Shadows was finished in 2016, completed in a wintry Oslo studio. But its roots go back a decade earlier, to a makeshift recording session in a Singaporean music store, the two musicians crouching over laptops in the dark as a security guard made his rounds beyond the locked doors.

Vinyl LP

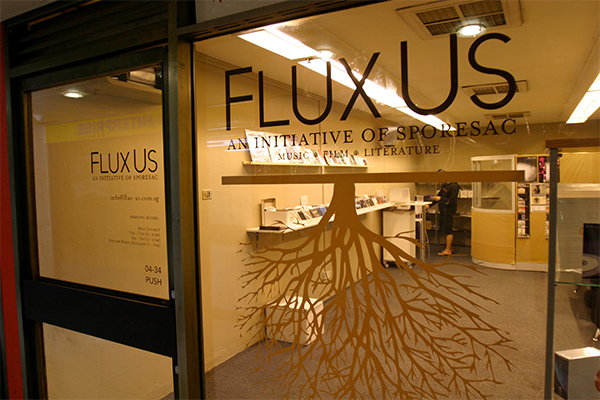

That store was FluxUs, a humble CD shop that, for a good year, stood as an outpost for experimental and avant-garde music in Singapore. Like many of the country’s beloved music institutions, it no longer exists. But its impact on the left-field corners of Singapore’s music scene still endures, like the spiky, long-buried electronics that leap out from In Praise of Shadows.

FluxUs was founded in 2005 by Harold Seah and Joseph Tham, two insatiable record collectors who were in their early 30s at the time. They met through a mutual friend while serving their mandatory two-year period of military service; they continued to bond over their musical discoveries with like-minded friends at university, many of whom were also musicians.

One of those friends was Yuen, who worked at the performance company Theatreworks and had invited Jazzkammer—the duo of Marhaug and John Hegre—to do a show called Pulse. Seah and Tham met the men of Jazzkammer through Yuen, striking up a friendship that the former describes as one of their earliest “real, friendly connection[s] to an international scene,” and the earliest inspirational impetus for FluxUs.

Seah and Tham first started to discuss setting up FluxUs in 2004. Their music-minded friends, who were excited at the prospect of properly sampling experimental albums at a local store, encouraged them. Once the pair settled on a unit on the fourth floor of Peninsula Shopping Centre (a dusty 45-year-old mall that has housed music and instrument shops since the 2000s), FluxUs came together in a matter of months.

“You’d be amazed at the lack of thought process [that went into starting the shop],” Seah—now a business consultant—says. “It was just done on a whim and a passion, finding defensive maneuvers to prevent ourselves from losing as much money as possible.”

FluxUs began business during a gloomy time for the physical music market. It had been a few years since Metallica beat Napster, but illegal downloads weren’t stopping. The global downturn manifested locally in the downsizing and eventually closure of music stores, notably Tower Records and HMV in Singapore.

“In 2005, some of us had already lost the feeling of music discovery in shops, and FluxUs actually rekindled it,” says Ricks Ang, a friend of Seah and Tham’s whom they roped in to operate the store. For lovers of experimental or left-field music, FluxUs was a garden of curious delights—but most of its stock merely reflected the collective tastes of Seah, Tham, and their friends, which had been cultivated over years spent mail-ordering records and reading The Wire.

Tham reels off three tentpole labels that, by and large, defined FluxUs: British institution Touch, the home of Fennesz, whose landmark album Venice was a shop bestseller; the Japanese label P.S.F. Records, which nursed fruitful relationships with Keiji Haino and Acid Mothers Temple; and avant-garde metal bulwark Southern Lord. Other labels whose CDs, T-shirts, and sometimes vinyl appeared on FluxUs’ Ikea shelves included Rune Grammofon, Erstwhile, Editions Mego, and Raster-Noton.

For some of the international labels FluxUs approached, it was their first time hearing from a Singaporean distributor, Tham says. And the inverse could be said of FluxUs patrons: Many discovered new music, artists, labels, and even movements when they visited the store and heard the albums the staff were playing. And even if they’d already been pirating albums, at FluxUs they could strike up conversations with the enthusiasts who staffed the shop and recommended music (Seah recalls pushing 7, a live DVD by Norwegian improv group Supersilent, to customers “like a lunatic, annoying everybody”).

The range of music available at FluxUs was particularly valuable to the Singaporean musicians whose laptop-enabled experiments with sound and noise sometimes felt undefinable, or at least liminal. Yuen was one of those tinkerers, as were Evan Tan (then a member of the avant-rock band The Observatory, and a keen fan of Touch’s catalog) and George Chua (who performed live with a laptop and released in 2006 Evidence of Things Not Seen, which was entirely crafted with the generative software Plogue Bidule).

The nebulous—and now ill-fitting—term “sound artist” was one that these laptop-wielding musicians identified with at the time, because it encompassed the breadth of their cross-genre explorations. Having a wide range of experimental music at his disposal via FluxUs, Yuen says, helped him better think through his own unpredictable music-making.

“The store opened us up to a lot of material to listen to,” Yuen explains. “To be able to reference stuff [through FluxUs] gave us some kind of understanding of what we do: ‘Kevin Drumm is doing very noise-based stuff. I’m also doing very noise-based stuff. Does this mean that I’m like Kevin Drumm, kind of noise-driven? But I also do ambient.’”

“Experimental music is such a broad thing, but I think [with FluxUs] we were able to see different forms,” reflects Ang, who remembers being particularly drawn to Japanese improvised music, as well as free and acid folk—interests that will not surprise those who know his work with April Lee as the ambient folk duo Aspidistrafly. “There was a special momentum at the time, in that there were artists spread around the local scene exploring new directions in music, who were interested in this kind of music. I think FluxUs really gave us all the reason to actually gather, and we gathered very quickly.”

Compact Disc (CD)

FluxUs’ free in-store gigs, in particular, became a notable reason for those gatherings: Artists would perform to the 20 or so people who could squeeze into the shop itself—as well as those peering in from the outside. In this intimate and informal setting, local musicians could improvise, engage in one-off collaborations, and—perhaps most importantly—play to a crowd who were game for offbeat or arresting experiences.

International acts passing through Asia would drop by Singapore and perform in-store at FluxUs’ invitation; glass-wielding noise artist Lucas Abela made a particularly lasting impression. Veteran and rookie musicians from Singapore’s small, porous experimental scene also performed, and even expatriate music lecturers from LASALLE College of the Arts, whom Tham dubs “fellow travelers” doing their bit to grow Singapore’s experimental scene, came into the fold.

Ricks Ang remembers Aspidistrafly’s performance at FluxUs fondly. The duo had made some ripples with the release of their 2004 debut EP, The Ghost of Things, but were ultimately unconcerned with fitting into the Singaporean mainstream. Performing to a small, but receptive audience at the store felt like a sign that, “we could continue doing this sort of music without having to set ourselves up to be popular or trendy,” Ang says.

FluxUs carved out space for the “weirdos” (a self-deprecating phrase that came up in my conversations often) of Singapore’s music scene, which was then expanding beyond the rock band-dominated status quo of the ‘90s. As a shop, it was open to all, and people from different artistic scenes, and seemingly far-flung corners of Singapore music—like the Mandarin music industry and the hardcore scene—dropped by.

“It was a physical space where people could come together and geek out over left-field music and art,” explains Singaporean artist Ang Song-Ming, who performed at FluxUs under the moniker Circadian. “As you can imagine, the crowd was mostly into not just experimental music but also arthouse film, outsider art, butoh, etc. This was something organic, which you can’t buy with money or state initiatives.”

As buzzing a social space FluxUs was for its patrons and performers, though, it was also still a business. After about eight months, Seah and Tham—who had kept their day jobs and worked at FluxUs on evenings and weekends—started to notice sales declining and stock ominously piling up. The store broke just about even every month, its modest profits channeled back into buying new records and refreshing its offerings. But even that was proving more difficult.

“There was a market of listeners that we didn’t distinguish from actual customers, people with that purchasing power,” Seah says. “You reach a point after a while where every customer becomes your friend. And that’s it, you know. You realize you’ve actually hit the limit of almost everyone who willingly wants to buy and consume physical media for that kind of music.”

In 2006, Seah and Tham downsized FluxUs and moved into a unit in nearby shopping mall The Adelphi, sharing the space with an audio gear store. It was practically a storeroom, Seah remembers; FluxUs eventually became a weekend operation. The next year, it closed for good.

Earlier in the store’s existence, Tham had fantasized about FluxUs becoming the Rough Trade of Singapore, he tells me. The duo even toyed with reissuing old Singaporean music through the store. But ultimately, “we knew that in Singapore’s context, we would never be like that,” Tham says. “We knew that it was just a castle in the air, kind of dreamy talk.”

Seah, for his part, had preferred to emulate Synaesthesia, the hole-in-the-wall experimental record store that existed in Melbourne in the early 2000s. (That store, too, was short-lived.) Together, we visited the Peninsula Shopping Centre unit that had housed FluxUs. Funnily enough, it is now a music school, with Christmas decorations up in April and some Elvis Presley merchandise on the walls. Seah remarked on how the place smelled different, probably because there was no cigarette smoke in the air. “It was good for what it was,” he concluded.

Ang agrees. “It was a good starting point for all of us, really,” he says. “While FluxUs gave us a home for experimental music, we needed to find our own paths.” While working at the shop as a twenty-something fresh out of school, he had gained a window into the music industry and connections to companies like p*dis, the Japanese distributor he still works with to this day.

Ang channeled his time and resources into KITCHEN. LABEL which, since its founding in 2008, has released albums that stand at the intersection of ambient, neoclassical, and the avant-garde. Besides artists from Japan and Europe, KITCHEN has also worked with Singaporean musicians, including sonicbrat, Hanging Up The Moon, and Kin Leonn.

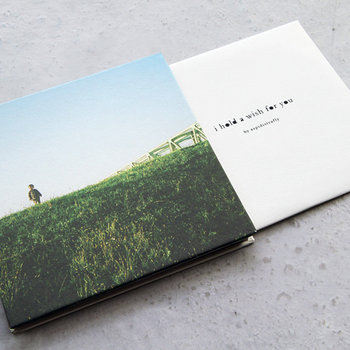

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

Yuen reflects on FluxUs in slightly more mournful terms. “It was a sad thing that it had to go. It was a feeling of back to square one,” he says. “It also made me think that maybe Singapore at the time was just not ready. Maybe we were being too ambitious.” Yuen, who is also a designer, had helped Seah and Tham conceptualize the store’s aesthetics and branding at its inception. He was also the one who suggested the name FluxUs, deliberately modifying the art movement’s name to highlight the word “us”: a nod to the shop’s origins in friendship, and Yuen’s own hopes that it would help nurture a community.

Today, Yuen and his bandmates in The Observatory (which he joined in 2014) organize events like shows and screenings. The work they do to nurture experimental impulses in Singapore’s music scene shares some of FluxUs’ community spirit, and owes some of its approach to the days of crowded in-store shows at FluxUs. Yuen points in particular to their BlackKaji live series. Held in intimate settings, BlackKaji gigs feature line-ups diverse not just in genre or sound, but also age, gender, and race. Yuen hopes these deliberately small shows, with a minimal barrier between artist and audience, can recreate what he calls the “sincere” and “genuine” listening that FluxUs cultivated.

The Observatory organizes BlackKaji in conjunction with the independent label Ujikaji Records, which nearly everybody I spoke to named as FluxUs’ most direct successor. Label head Mark Wong was a university student when he patronized FluxUs, and had actually spoken to Seah, back in the day, about starting a label. “Ujikaji was created to fill a gap left by FluxUs’ exit,” he explains, bringing experimental releases to Singapore that FluxUs would have distributed had it still been around.

Today, Ujikaji operates both as a mail order business and a purveyor of homegrown sonic experimentation (its name means experiment’ in Malay). Its shared DNA with FluxUs is clear from the albums it has released thus far: Ujikaji put out In Praise of Shadows, as well as records by or featuring Tim O’Dwyer, Awk Wah (aka Shark Fung), and The Observatory—all artists who performed at FluxUs back in the day.

More than a decade after the store’s closure, people still ask Seah and Tham if they would ever revive FluxUs. For both men, the answer is always no. Not only would it be impossible for the store to survive today, Seah says, other players have more than fulfilled the role FluxUs—sometimes inadvertently—played incubating experimentalism in Singapore’s music scene. “People are doing it better with more focus and dedication,” he notes. “What’s the point of walking back into a crowded market?” If FluxUs was a Skynet prototype, he quips, Ujikaji is more akin to a T-1000.

The Terminator analogy is but a wisecrack, but it also belies a lesson that feels particularly pertinent in a country where artistic spaces always seem to operate on borrowed time, whether their demise comes at the hands of expensive rent, bureaucratic indifference or the property market’s profit-driven insistence on upheaval. For Singaporean musicians and creatives at large, FluxUs’ long, generative afterlife may act as something like a balm for anxieties about longevity and sustainability. It serves as a vital reminder that even if things don’t last, it doesn’t mean they’re not worth doing.