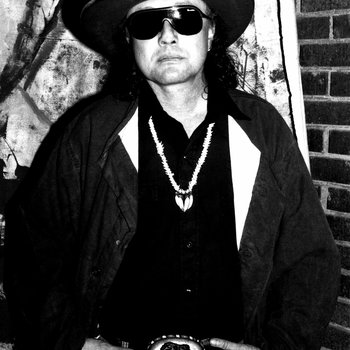

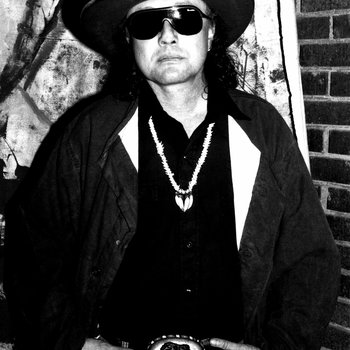

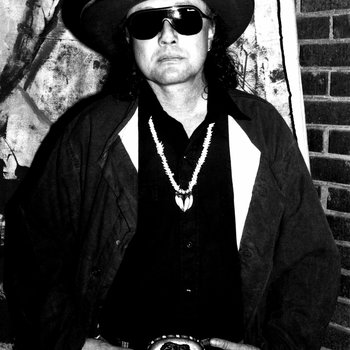

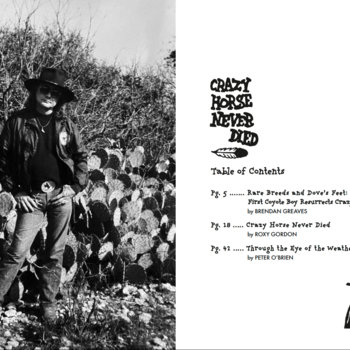

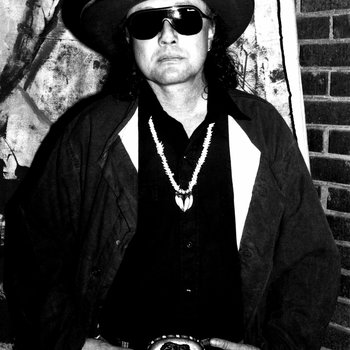

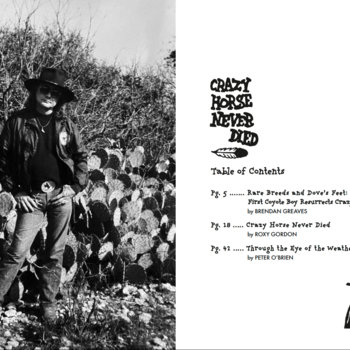

Writer. Journalist. Poet. Publisher. Musician. Visual artist. Visionary. An American Indian activist. A man of Choctaw and Assiniboine heritage. Husband. Brother, not by blood but in spirit. Friend.

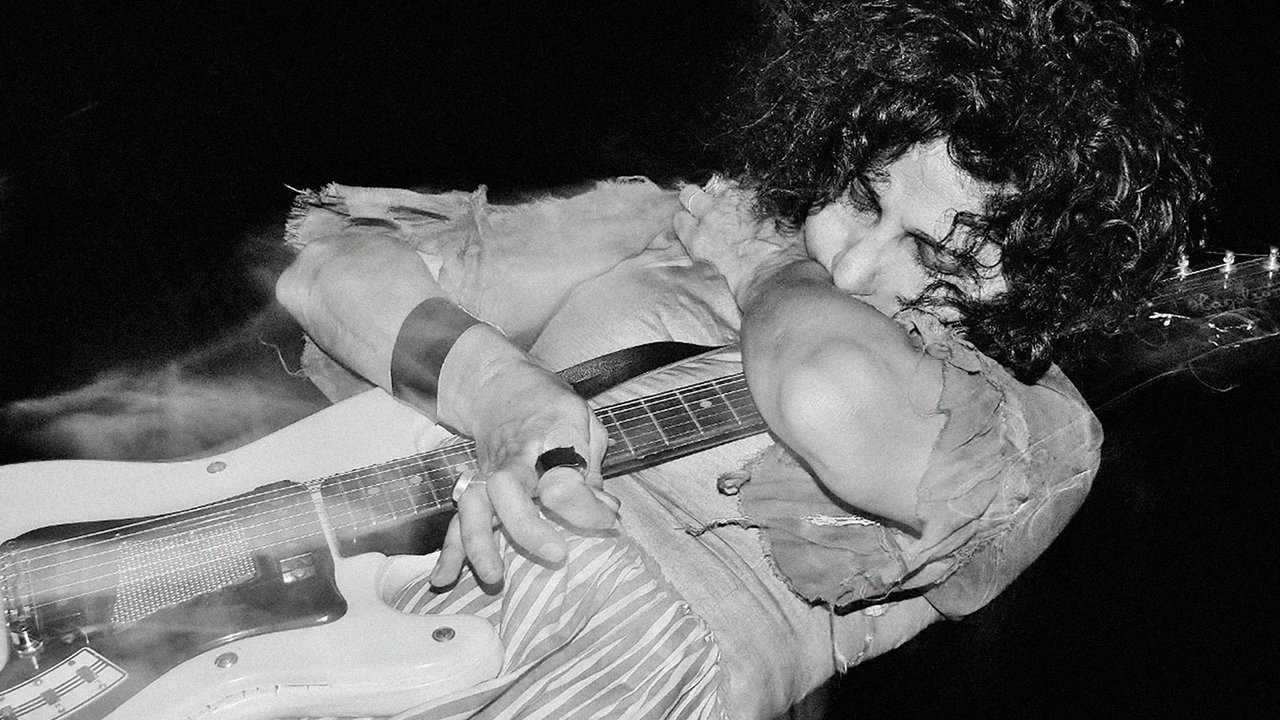

More than 23 years after his death, people still can’t seem to narrow down the words that best describe American artist Roxy Gordon.

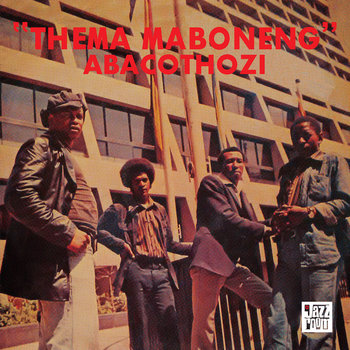

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Book/Magazine

“My dad was a storyteller, first and foremost,” says Roxy’s oldest son, J.C. Gordon, who grew up both in his parents’ art-stuffed Dallas home and on family properties in rural Coleman County, Texas. “It didn’t matter if it was about country music. It didn’t matter if he was writing for music magazines. It didn’t matter if he was doing poetry. He was a storyteller.”

“His identity was multivalent. He was never one thing,” says Brendan Greaves, whose North Carolina-based Paradise of Bachelors record label is reissuing Gordon’s 1988 album Crazy Horse Never Died. “I think he struggled with how to define himself throughout his life, and all those aspects of his identity weren’t necessarily at odds, but they were always present in him.”

“Roxy is without a shadow of doubt the most remarkable person it’s ever been my good fortune to know,” says Peter O’Brien, a British journalist who published Gordon’s work and originally released Crazy Horse Never Died. “He and [his wife] Judy just showed wonderful kindness to me over many, many years of going there and spending time there.”

For J.C. Gordon, however, Roxy Gordon was primarily Dad—the kind you live with, learn from, and love before veering off to establish your own path in life. For a couple of decades after he left home, J.C. was well aware of his father’s work as an artist and activist, but from a distance. And he was not deeply invested in the mythos around the man even though he had inherited an extensive collection of Roxy’s writings, recordings, and art after his death in 2000.

“My parents did a good job of keeping all that stuff together,” he says. “What they didn’t do a good job of was categorizing it. So I just had all this stuff in boxes.”

In the 2010s, J.C. was approached by multiple parties about publicly distributing or displaying his father’s work, but he largely disregarded those inquiries—including emails from Paradise of Bachelors—until the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020.

“One day, I just kind of thought ‘What in the world would he have thought about the world today?’” J.C. says. “And I guess that was the first time I realized I missed my dad.”

In those boxes of Roxy Gordon’s work, J.C. realized, was an opportunity not only for him to have a relationship with his father, but also for other people to experience Roxy’s raw art and unique perspective on the intersections of American Indian and European American culture, framed through the lenses of history, identity, oppression, and imperialism.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Book/Magazine

“A lot of people were fascinated by his storytelling, you know?” J.C. Gordon says. “He did a lot, and I just decided that I wanted to move it out into the world.”

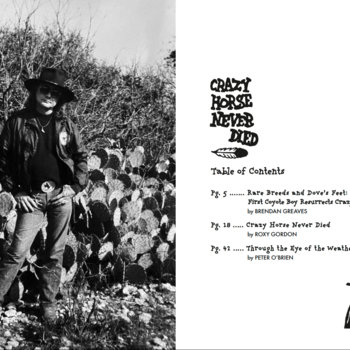

So he started scanning photos, artworks and writings and posting them online, and he got back in touch with Paradise of Bachelors, whom he had ignored for years. Now in a more receptive mindset, he started working with Greaves and label co-founder Chris Smith on a reissue of Crazy Horse, a collection of spare and unsettling spoken word pieces set to peculiar synth rock, homespun country, and outsider folk music. On “An Open Letter to Illegal Aliens,” one of the album’s most striking songs, Gordon directly addresses European colonizers who brought capitalism, materialism, and ecological degradation to the Americas as a church-like organ churns in the background:

Even after you’ve overrun ‘em/

Taken their jobs/

Stolen everything you could steal/

Still, man, they’ll let you stay.

It ain’t you, you see, illegal aliens/

That these American continents don’t want/

It’s that baggage that you slipped through customs/

Send that baggage back, man/

You can stay.

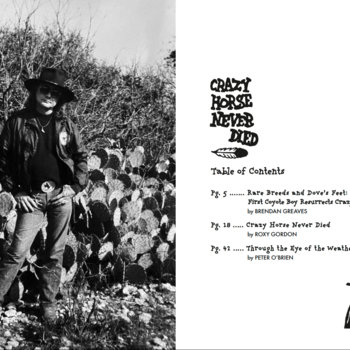

The project is more than a decade in the making for Greaves and Smith, who first talked about reissuing Crazy Horse after hearing Gordon on a mutual friend’s mix CD of Native American music in 2012. Both men recognized Gordon’s name—and the album’s striking red and yellow cover art—from years of crate digging and exploring fringe music.

“It’s just such a gut punch of an album,” Greaves said. “I don’t think we even paused to think about [whether to reissue it]. It was just, like, ‘Let’s do it.’”

The next several years required patience and perseverance. Greaves and Smith started out talking to Judy Gordon, who didn’t see much value in revisiting her husband’s work. As they lost touch with her, they connected with some of Roxy’s musician friends as well as O’Brien, founder of Sunstorm Records, which initially released Crazy Horse in 1988. That crew put them in touch with J.C. Gordon, who was “deeply suspicious of us and our motives,” said Greaves, “and understandably so.”

But with reassurance from both O’Brien and Terry Allen—Paradise of Bachelors recording artist, Texas singer-songwriter, and Roxy Gordon’s friend—Gordon eventually set aside his skepticism and began working closely with Greaves and Smith on bringing Crazy Horse back into print. That was the goal all along for the record label guys, who stuck with the project for 10 years because they believe in what the album, and the man who made it, has to offer listeners.

“It’s such a unique record that held an experience like the first time I heard other records that stuck with me forever—a real communication of otherness and unified human emotion,” Smith said. “I felt like I was privileged to hear it, and when I started looking into who Roxy was, every moment of discovery about him revealed the depths of his character and the more he became this larger-than-life figure.”

Writes Greaves in the spectacular chapbook that accompanies Crazy Horse: “I find Roxy’s voice—the sometimes unlovely, piercing sound of it, its grim humor, and its bemusement about our share culpability and onrushing mortality—arrestingly strange and singularly moving.”

O’Brien felt the same way back in the early 1970s, when he first asked Gordon if he could reprint some of his writings for O’Brien’s burgeoning magazine dedicated to left-of-center country music, Omaha Rainbow. The two became fast friends, and O’Brien traveled from England to America a number of times to visit the Gordons at their home in Texas.

“He had just this incredible way of talking, and we would travel out to his parents’ place in Coleman County and he’d tell stories all the way out there,” O’Brien says. “And he never got the widespread recognition he deserved for his writing. The pieces he wrote for Omaha Rainbow were wonderful, every one without exception.”

“It’s never too late,” he says, “for Roxy to find his wider audience.”

For J.C. Gordon, caring for his father’s work is both an intensely personal project and an effort to preserve the legacy of a man who makes more sense to him now than ever before.

“I’d be somewhere with my parents and they’d be talking to someone new, and they’re telling the same stories. They’re new to that person, but I’d heard them 30, 40, 50 times,” Gordon says. “I just wanted to play Dungeons & Dragons and watch Star Trek on TV. I mean, I was totally the opposite of what my parents were.”

In recent years, however, Roxy’s work has not only provided a foundation for J.C.’s philosophies and approach to life, they’ve given him a sense of place and self that he sometimes struggles to find in the world. He believes they can do the same for others, too.

“[Eventually] I realized that my dad’s stories are as valid today as they were way back then. In fact, I think there’s even more need for that type of storytelling. There’s more need to connect to the past through history and through stories,” he says. “And that’s what my father was very good at. That’s what people came to him for. And sure, he’s not writing anymore. He’s not producing music anymore. But his work still resonates with me, and I believe it will resonate with people who have felt the full force of the government or whoever is holding the power.”