There are few labels that capture the pulsating beat of a particular music scene better than Dischord did for Washington D.C. punk in the ’80s and ’90s. To mark the occasion of the entire Dischord digital catalog coming to Bandcamp (plus vinyl from Minor Threat and Fugazi), we sat down with a few people who were there in the early days and still hold the label near and dear.

Joe Gross hails from Falls Church, Virginia. He has written for Spin, Rolling Stone, the Village Voice, the Washington CityPaper, Radio On and others and is working on a 33 ⅓ book on Fugazi’s In On The Kill Taker. He covers culture, popular and un-, for the Austin American-Statesman, and lives with his family in Austin, Texas.

Aaron Leitko is a musician and journalist based in Washington, D.C. For the last four years, he has worked at Dischord full time, handling press and promotions, among other things.

Jason Farrell is a musician, graphic designer, and filmmaker. He has been active in D.C. bands since 1985 (Bells Of, Swiz, Fury, Bluetip, Sweetbelly Freakdown, Red Hare), and has designed covers for Dischord since 1993.

Chad Clark is a musician and recording producer/engineer based in D.C. He was in the bands Smart Went Crazy and Beauty Pill, both of whom were on Dischord Records. He also remastered the Dischord catalogue.

Jes Skolnik is Bandcamp’s managing editor and a former D.C. punk (still punk? But now of Chicago/New York). An active member of Positive Force and Riot Grrrl in their youth and a member of numerous bands that nobody ever cared about, they have been writing about music in one venue or another for the last couple of decades.

What was your entry point to Dischord? How did you find out about the label?

Gross: I grew up in the D.C. suburbs, but my high school was Not Very Cool. I can count the folks in my orbit who were involved in the D.C. scene on the fingers of one hand. I was also never a hardcore kid, not really. Punk, yes; hardcore-as-genre, no. It was all second wave sXe/youth crew at the time, and it was just not for me. I was way too much of a wuss for that shit.

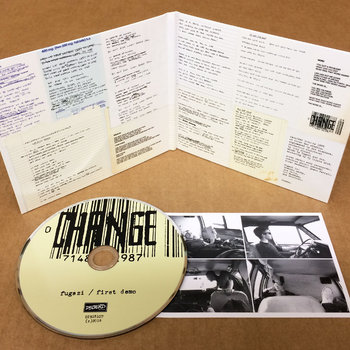

That said, I was over at a pal’s house for dinner with some friends, and she was dating a guy a few years our senior who was in the scene. She put on a tape of the first Fugazi EP —a record that had been out for a few months, at most. I literally don’t remember anything else about the evening. I heard that bassline for “Waiting Room” and I just stared at the speaker. It is one of a handful of albums where I can tell you exactly where I was and what I was doing the first time I heard it. I was floored. I had to know absolutely everything about them, and about the scene, and about D.C. punk from that moment on.

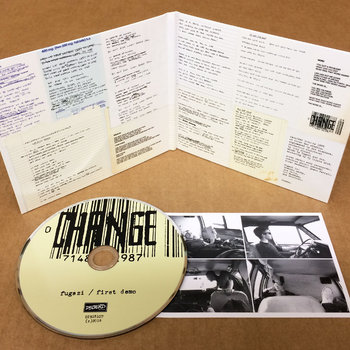

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

Farrell: I am sorry that sXe was your first exposure. That stuff was horrible, and I was bummed when it was seeping in and homogenizing a genre that I grew up on.

Gross: It’s funny—I enjoyed the first wave stuff once I heard it, especially Void. But I got to college and was severely anti-hardcore-as-sound. Some good friends were like, ‘OK, you only know the very worst shit,’ and introduced me to stuff on Gravity and Slap-A-Ham and Old Glory and that early ‘90s stuff and I was like, ‘OK, this is tremendous.’

Farrell: My friends and I came to punk and hardcore by way of skateboarding in late 1983. The older, louder kids who showed up at our shitty quarter pipe would spray paint band names we’d never heard of on it. Our freshman year of high school was a crash course in all things punk, leading eventually to Minor Threat. We were surprised that 1) There was a thriving hardcore scene in our town, and 2) Someone could get away with putting so many swear words on a record. Once I started listening to D.C./Dischord bands, I pretty much stopped listening to anything else for a while.

Compact Disc (CD), 7" Vinyl

Leitko: I had been aware of Minor Threat and Fugazi when I was growing up in Salt Lake City, but my real entry point to the Dischord world came when I moved to D.C. for school during the early ’00s, and started going to see bands like Black Eyes, Q and Not U, and Antelope. It made a difference that it was something I could be present for, rather than just experiencing the music on a CD.

Clark: I’m a weirdo. My love of Dischord Records came at the time when the label was conspicuously moving away from anything that could be characterized as ‘hardcore.’ The first Dischord thing that I truly, truly, truly loved was Shudder To Think. This was a band that aesthetically scandalized a lot of people, but they were thrilling to me.

Farrell: Very odd music when it came out, for sure. Shudder had to be embraced to be enjoyed and understood. But they came at a time when people—boys, especially—were not wholly comfortable with the idea of embracing. They were beautiful, though. My first band, which was decidedly hardcore, toured with them at the beginning of their exploration. People either loved it, or felt really uncomfortable with it, which is why i think Shudder are amazing. Aaron, had you seen many DC bands before you moved to DC?

Leitko: I hadn’t seen any. At the time, I don’t think it was very easy to find all-ages shows in Salt Lake. I may just not have been in the know, though. My older cousin had a bunch of Dischord releases, though—Make Up, Lungfish, Fugazi, etc.

Farrell: By virtue of geography, bands would be forced to tour through SLC on the way to Cali. I feel like this happened in a lot of places, planting seeds across the country.

Skolnik: I also came to Dischord by way of geography. I was born in D.C. and grew up in Silver Spring, and my dad, an electrical engineer, ran an amp repair shop out of our basement before I was born. He’s a sound engineer too. He was my entry point. He bought me the Minor Threat discography when I was an annoying little skate brat/metalhead because he thought I’d like it, and it pretty much broke my world open. From there, I started going to Positive Force meetings, Riot Grrrl meetings, etc. I lived on that long-ass Metro ride from Silver Spring to Arlington.

Let’s talk more about geography. Dischord is so firmly rooted in D.C. Why do you think that is?

Skolnik: I think that’s the nature of all local punk scenes, really, but Dischord is so community-minded, and there are so many references to other local bands, political movements, monuments, and places throughout the entire catalog, both visually and musically. And I learned the ethics of being part of the community and the idea of giving back from Dischord and Positive Force. You didn’t just have a show in a church basement, you did a benefit for the needle exchange that that church hosted on the weekends. I always think about something I’ve heard both Cynthia Connolly and Ian MacKaye talk about: that D.C. didn’t have a larger punk scene, so they had to make their own. There’s something fiercely provincial about it that I honestly like a lot. D.C. doesn’t get enough credit, ever.

Gross: It was massively important to me. The idea that all of this stuff was near me—I felt a sense of ownership, of sorts. I adored its regional focus. Dischord was like a folk label in that way, and I really dug that. To this day, I have a bit of a knee-jerk, I-will-give-this-a-spin reaction to bands from anywhere from Richmond to Baltimore, and Dischord is a huge part of the reason why.

Clark: I think I remember talking to Ian about the label’s focus on regionality, and I think he said that he always expected other labels to conduct themselves that way. Like, it was a natural characteristic of independent labels to reflect where they came from. That makes sense to me.

Farrell: There were many other local labels representing their scenes. Dischord followed that same idea, but did it quite well. None lasted as long.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

What was your first Dischord purchase? Where did you get it?

Gross: Man, I taped a whole mess of stuff from pals before I actually plunked down money. I have a very strong memory of going to Olsson’s at Metro Center the week or so that Fugazi’s Margin Walker EP came out, and there was just this wall of them in the back. It looked like the only record they cared about that week, which was appropriate. I purchased the tape—I didn’t trust my parents’ turntable—and had my wig pushed back all over again. From then on, I purchased almost everything the label put out, and was happy with it a good 75% of the time—which is a pretty good ratio.

Skolnik: Plays Pretty For Baby was the first one I bought with my own money. I made my dad take me to see Bikini Kill and Nation of Ulysses (thanks, dad) and I just got hooked on both of them in the weirdest ways. I think both of those bands have affected my personal trajectory in kind of hilarious and monumental ways. After that, it was pretty much like, ‘I’m gonna buy every single goddamned thing on this label.’ Labels and liner notes: the solitary tools of music discovery pre-Internet.

Leitko: I relied heavily on my family and my college roommate’s CD binder for a lot of the classics. I think the first thing I bought was a CD copy of Lungfish’s Sound in Time. I picked it up at Smash! back when the store was located in Georgetown.

Clark: It was probably Dag Nasty’s Can I Say? This album remains a big bubblegum pop hit to me. I don’t mean ‘bubblegum’ disparagingly. I mean it’s as infectious and melodically confectionary as any classic pop record.

Vinyl LP

Farrell: Faith, Subject to Change. But I didn’t buy it—I traded a lightly-used copy of [Government Issue’s] Boycott Stabb for it. Crazy to see all these different and distinct eras as being your entry points.

Skolnik: It’s so interesting how temporal it is, and how much that affects everyone’s trajectory.

How did you get involved with working with the label?

Clark: My particular history in this respect is weird. I had never intended to be an artist on Dischord. My dream was to be on Adult Swim, Jeff Nelson’s boutique side label. They had released Girls Against Boys albums that I admired, and they had put out these lavish 9353 reissues. By the way, 9353 is a legendary, storied, arcane band that should probably have a documentary film about them. I’m not sure they can be characterized as ‘punk’ in any way, but I don’t know.

What impressed me about Adult Swim was that there was a lot of attention to detail in the packaging. And there seemed to be no identifiable musical aesthetic. I thought that was cool: I make hard-to-define music, here’s a hard-to-define label.

So I sent a demo to Jeff, who I didn’t know at all. He got back to me very quickly to tell me he thought the music was amazing, but he was very honest that Adult Swim was pretty much out of money. That’s what happens when you put out very obscure records that you spend a lot of money on.

Then he said, ‘Would you consider Dischord?’ Honestly, I hadn’t considered Dischord, because I kinda thought—like a lot of people—‘That’s that hardcore label…’ But then my friends talked sense into me, and I said yes. I already knew Ian [MacKaye] socially, but had never introduced myself as a musician. I was kinda shy. At some point, Ian said to me, ‘Jeff told me you’re in a band…’ He seemed almost annoyed that he had to hear it from Jeff and not directly from me. It was a funny circumstance. And the rest is history.

Skolnik: Chad, I have wanted to do a historiography of 9353 for a long time. Just a side note. What a fascinating band.

Clark: Yes, fascinating.

Gross: Jesus, that band was weird. That band actually made me a little nervous.

Skolnik: I was describing 9353 to someone who, like myself, suffers from deep organic depression, and I was like, ‘You know the narratives you tell yourself when you’re at your worst? 9353 sounds like those, warped and collaged and manipulated.’ Legit the weirdest. There has never been anything else that sounded quite like it.

Farrell: I remember when Smart Went Crazy were about to be on Dischord. I was doing a lot of covers for the label then, and I recall the scratching of heads in the office. But it only took a short while to see that band fully embraced, and eventually merging with and altering the trajectory of the label. I mucked through the graphic needs of my first band, Swiz, out of necessity. That led to a job at a pre-press/print shop where I learned a ton about the process, and began doing covers for other bands.

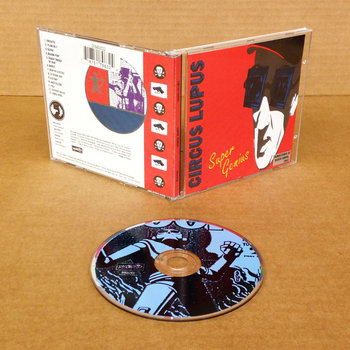

In 1993-ish I did a 7” cover for Desiderata (Amanda MacKaye’s band)‚ it was a half-label Dischord release. That led immediately to three full-length layouts for Dischord: Severin (Acid to Ashes), Circus Lupus (Solid Brass), and Fugazi (In On The Kill Taker). Dischord and D.C. in general were on a big upswing, putting out lots of records. The talented and influential Jeff Nelson had stepped back a bit from doing all the Dischord layouts, leaving room for me and others to crank through some covers. I’ve been working with them ever since, laying out covers for Fugazi, Lungfish, Make-Up, Dag Nasty, Embrace, Rites of Spring, etc. Between 1996 and 2001, Dischord put out albums for my band Bluetip, and since 2013 they’ve put out records for my new band, Red Hare.

Leitko: Back when I was working as a music journalist in a more full-time capacity, I would write to Dischord label manager/Lovitt Records founder, Brian Lowit, to ask why certain writers and publications hadn’t been serviced with promos. I was bummed that then-active bands—like Medications or Antelope—weren’t getting covered as much in some of the publications I was both reading and writing for at the time. Eventually, around the time of Void’s Sessions 1981-83, he and Ian asked if I might want to try doing some freelance promo work for the label. After a year or so of that, I was able to come on full-time.

Clark: I keep forgetting to mention that I did audio work for Dischord for about a decade. This was much later, after Smart Went Crazy ended. I helped to get the remastering program off the ground. I think Ian recognized that I have an intense relationship with sound, and that I paid a lot of attention to the way records were shaped sonically. So I think he wanted to access and exploit that passion (I don’t mean ‘exploit’ darkly, I just mean ‘make use of’) in service of the label’s amazing catalog of work. So we went about remastering the catalogue. One of the great honors of my life.

Skolnik: I never formally worked for Dischord, but because of Positive Force, my teen and early adult years were spent manning the door at a lot of Dischord/Positive Force shows. I have seriously never been more proud to do a dumb-but-necessary job in my life than I was sitting at that table. ‘YOU SHALL NOT PASS, DRUNK PUNKS WITH $2.00 AND A 40.’ Thinking about it now, one of the neat things about growing up in DC during the time that Dischord was a really active label was the fact that it was so easy to get involved. Like Joe says, there’s really a sense of ownership there, even if you’re an outsider.

Gross: “No violence, no thuggery, no boyhood bullshit…what?…OK, no girlhood bullshit, then.”—Ian MacKaye

How do you see Dischord’s strong ethics at work in your life now, if at all?

Gross: Oh, man. One of my earliest Dischord purchases was the State of the Union compilation. That thing was incredible. If you’ve never heard it, it’s kinda like Flex Your Head for the mid-to-late ’90s Dischord sound. It was assembled, I think, by the folks at Positive Force. Some of it has not aged well, but it has great songs from Ignition, Soulside, One Last Wish, Rain, etc. Oddly, one of the few Fugazi songs I dislike is on there. Anyway, there was this booklet in there that is just one of the all-time great late-80s political punk documents, full of info about companies worth avoiding, vegetarian stuff, that sort of thing. I am sure some folks found it didactic as hell, but I found it inspiring. There is a photo in there of Tomas Squip (Beefeater, Fidelity Jones, general oddness), naked, with the words ‘Lord, let me do no wrong’ on his abdomen. I was like, ‘OK, these guys mean business.’

That thing made a huge impression on me. And I know various bands had different relationships to politics, but the lack of interest in separating art and politics on a band like Fugazi’s part was and is endlessly inspiring.

Skolnik: Hippie-parents-plus-D.C.-atmosphere meant that I was already primed to be an activist on the spectrum of pinko-to-anarchist, but Dischord firmly imprinted that on me. Built into the ethic of the art is that it is inherently political, in its form and function, even if it’s not didactic (and some of it was). And it’s community-oriented, local, specific. Not big and posed and theoretical. Granular. That’s informed everything I do, everything I am. Also, just that general sense of fairness and responsibility.

Clark: To me, I see the label as a badge of sincerity. That’s what the logo signifies to me. ‘We mean it.’ Semiotically, that is the weight of what you feel when you see that logo. But I take so many of its principles into my life, and it continues to be empowering. I also like the idea of ‘Don’t wait for permission or authority.’ That helps in artistic things. I just jump into doing things without any kind of ‘credentials.’ It’s fun, and you can achieve so much more if you’re not timid.

Gross: ‘Never ask permission, the answer is always “no”’ is one of my favorite MacKaye-isms.

Clark: My use of technology in Beauty Pill is very punk-informed. I know there is some irony in this, because Ian often disparages technology as a ‘drug everybody is high on.’ But I jump into technology that I don’t understand all the time! And I feel no fear. And I don’t worry about being an ‘expert.’ And this liberty has helped me to excel. So I’m forever grateful to the label for that tenet.

Farrell: The Dischord work ethic is very similar to skateboarding when I came to know it. If you wanted to ride something, you had to build it. So you had to learn how to build. A ton of enthusiasm, coupled with a crude understanding of hammer, nails, and wood gleaned from building tree forts would be the basis for a series of horrible ramps. But each one got a little better. Eventually, you’re good enough to build a house. It’s the same with music: it’s borrowed instruments plus a little talent, and bash it out until your skills catch up with your enthusiasm. I still live by that way of thinking: Don’t let not knowing how to do something stop you from doing something. Just get started—figure it out.

What’s your fondest Dischord-related memory?

Clark: For me, every private consultation I’ve ever had with Ian. I think this is the main way you get ‘paid’ when you’re an artist on the label or someone who works at the label—you get these amazing chats over tea. They are so inspiring and stimulating. Anyone who has worked with the label knows what I’m talking about. Ian is a really interesting and wise guy. I mean, that is what he’s famous for, but it takes on a different character when you’re with him one-on-one. I’ve benefitted enormously from the wisdom I’ve garnered from talking to him in his dining room, sipping tea. I mean, I have argued a lot with Ian. I don’t agree with everything he says. But I recognize him as a towering intellect, and someone who has contributed enormously to my life with just his thoughts. He has my eternal respect. That doesn’t mean he’s right about everything, though…

Farrell: There are so many eras and styles, as one would expect and hope for with a label in its mid 30s, and the label is attached to so many memories for me. It’s hard to sift through all of them. As a listener, I still remember the feeling of getting the Salad Days 7”, of hearing Void for the first time, of seeing Rites of Spring.

As a designer, I remember the time I fucked up one of Guy’s lyrics on the Red Medicine artwork—I’d typed ‘shout out and shoot out the windows,’ when it was supposed to be ‘shadows.’ Not a happy memory, in that he was clearly bummed. But I thought it was funny when Ian said, ‘I like it better.’

As a musician, I was honored to be on the label with Bluetip—to be among the bands I’d grown up loving, contributing in our small way to the archive and legacy, but still feeling separate from it—still feeling like way more of a fan than a contributor or employee.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Skolnik: I was in a communication arts magnet in high school. My pre-freshman summer project was to take a camcorder and shoot a ‘What I Did On My Summer Vacation’ reel and edit it together. I basically spent the summer taping Fort Reno shows, but it was the summer of 1993, and I videoed that entire Fugazi Washington Monument show in August. That footage and that experience sticks with me as this defining who-I-am-and-who-I-will-be thing: being part of the crowd, but not of it. Observing and recording music that makes me feel like I am going to happily explode. I feel so incredibly lucky that was what I got to do with my summer, and that was the path that ended up defining who I would grow into as an adult. This is so corny, but it’s true. Also, I remember writing a letter to my friends in Q and Not U at a Black Cat show sometime in my early 20s. I was watching young kids a generation behind us watch them, and I was thinking about how they were getting kids into music the way the bands of the previous generation did for us. When I talk to people who are five to seven years younger than me now, Q and Not U were a huge gateway band. Watching your friends have that moment is really sweet and cool, and I’m still proud.

Gross: As noted above, hearing that first Fugazi EP was a stone life-changer, up there with first exposures to Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat, Stooges’ Fun House, Cramps’ Off the Bone, and Public Enemy.

Leitko: I remember seeing Q and Not U play in the basement of a GW dorm during my first year of college. I’m not even certain they were on Dischord at that point. I was into it, but they were a local band, and not all that fundamentally different from anybody else playing music in or around my school. Months later, I went back to Salt Lake, and there was already a note posted in the record store by somebody seeking musicians who wanted to start a band influenced by Q and Not U. It made me suddenly very conscious that this music that I had witnessed in a basement had made this larger connection with a bunch of people very far away.

Vinyl LP

What three Dischord releases would you recommend people unfamiliar with the label check out first?

Gross: For hardcore stuff, Flex Your Head or the Minor Threat discography. Then, the Rites of Spring album, which remains one of the best rock albums of the 1980s, full stop. Maybe the 20 Years of Dischord box, which is as close as they ever got to an overview of the late 80s-to-00s era of the label. And, come on, any and all Fugazi.

I will also rep hard for the first Circus Lupus album, Super Genius. That is an incredible record: great songs, great ranting from Chris Thomson, great drumming from Arika Casebolt, who sounds like nobody else. And for the Happy Go Licky compilation. If those dudes had gotten it together to record a proper studio album, I swear it would be as well known as any punk record from ‘87. And my Lungfish fandom moved into the ‘slavish’ category some time ago—I love all their albums, but Pass and Stow is the one I put on if I feel like having that dude-in-front-of-the-speakers-in-the-Maxell-ad moment.

Compact Disc (CD)

Leitko: Lungfish, Love is Love, Slant 6, Soda Pop*Rip Off, Antelope, Reflector.

Farrell: The Rites of Spring 12”, because it’s beautiful—perhaps the first beautiful record I heard out of a notoriously un-beautiful lineage. Fugazi, Kill Taker (not because it’s their best, but because it’s relentless, and maybe my favorite). Lungfish, Sound In Time—or any of them really.

Clark: My answer is going to be 100% Fugazi. For me, In On The Kill Taker, Red Medicine and End Hits. I’m actually of the opinion that Fugazi never made a bad album, but that particular run is just majestic.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Farrell: Yes, Chad, a good batch. I’d swap The Argument for End Hits, only because it crept up on me from dislike to surpassing many of the other albums. Kill Taker is perfect.

Gross: End Hits has its own cult within the Fugazi cult. We should have jackets made.

Skolnik: I love Lungfish so much it hurts. So much! I am going to say SLANT 6 SLANT 6 SLANT 6, because I am such an ultimate fan for that band. I did a show for them once as a teen, I was in a Slant 6 one-off cover band, wrote an essay about Inzombia—I think my fandom might border on creepertown? If so, I am sorry. But man, I love that band.

Vinyl LP

Clark: ‘Nights times nine packs great power, POWER!’ Is that the actual lyric? Or am I getting it wrong?

Skolnik: Chad, that is the line!

Clark: That is great shit. I mean, I have no idea what that means, but it’s absolutely genius at a phonetic level.

Leitko: I once heard a story that this particular line was inspired by the text on a can of bug spray. Don’t quote me on that, though.

One of the many amazing things about Dischord is how it provides a reliable snapshot of what was happening in that corner of the D.C. punk/indie rock scene at that particular time. Philosophical question: As punk hits 40, what do you think is the value of a ‘punk archive’?

Gross: I have no problem with it whatsoever. More music is more music. Of course, your relationship to it is not going to be ‘in the moment,’ but that’s fine. I mean, do I wish sometimes that Dischord put out more records by younger DC bands? Sure. But if the label is going to be a document of, what, maybe 50 or 60 people in a particular time and place, then it’s gonna be that. And that’s OK.

Farrell: I don’t know. it’s good reference. It also makes me sad. It makes me realize how much music I’ve dismissed. Rock, blues, jazz, even classical were all cutting edge or dangerous within the eras they existed, but to me they were all old dead things echoing through the radio. I now know I was wrong. Those people must have felt something similar to what I felt as I watched a good chunk of this punk thing happen. It’s weird to see this part of the D.C. continuum conscripted to history, trapped in amber and on display, because I saw it moving, living, growing. But I didn’t see the beginning, and skimmed over some of what followed. Perhaps there is comfort in knowing you’re always somewhere in the middle, and this thing will continue.

Skolnik: Yeah, I worry about punk as iconography, as signifier, as commodity, as opposed to punk as living breathing thing. I am glad for archives, but also have seen so much excluded and so much distorted because of what ends up in the stacks and what doesn’t. I also feel like, while it’s great to learn about music you might have missed and about its context, there’s the ability for the archival impulse to freeze something out of the present day and break it from continuity. That scares me. Punk nostalgia is wonderful, but it’s also dangerous. I want people to keep wrecking shit in the present day more than I want us to look backward—which I know is paradoxical, because we’re reflecting back right now!

Gross: Jason, I don’t know if I see it that way. I think you never know who is going to be inspired by an old album, who thinks of putting a song together differently after hearing a Fugazi album or a Jawbox song or something. I just don’t think we can know how someone is going engage with something. I mean, records by the Beatles, Stones, Howlin’ Wolf, and Mozart are still blowing young minds. And, agreed, Jes: Once something becomes ‘past,’ who controls that narrative becomes awfully important. And I agree 100% that punk-present is more important than punk-past

Farrell: Joe, I’m not saying Dischord or broken-up bands can no longer inspire, and, yes, having a comprehensive archive will ensure it does. I just mean it’s both sad and somehow beautiful to see something be born, grow, and die. Other things come and take their place. It’s life. It’s sad, exciting, beautiful.

Clark: I’m not particularly interested in punk rock as a sound. (I think this is probably self-apparent in my work.) Punk aesthetics are alright—I like the emphasis on organic communication and simplicity and directness—but what I think is enduringly interesting and valuable is punk thought. To me, that’s what the Dischord catalogue embodies: Punk thought.

I once asked Ian how it was that he came to identify all of these eccentric geniuses in his own community. Ian seemed to have a gift for identifying superpowers. I mean, right here on this panel we have Jason Farrell, whose gift for design is no joke. And there was Dan Higgs, of course, and Ian Svenonius—I mean, think about meeting both of those people in one lifetime! And Craig Wedren? And Guy Picciotto? And J Robbins? And Christina Billotte? The list goes on. I asked him, ‘How do you keep finding these amazing fucking people?’ Ian’s answer was simple:

‘I look for the ones who can’t help it.’