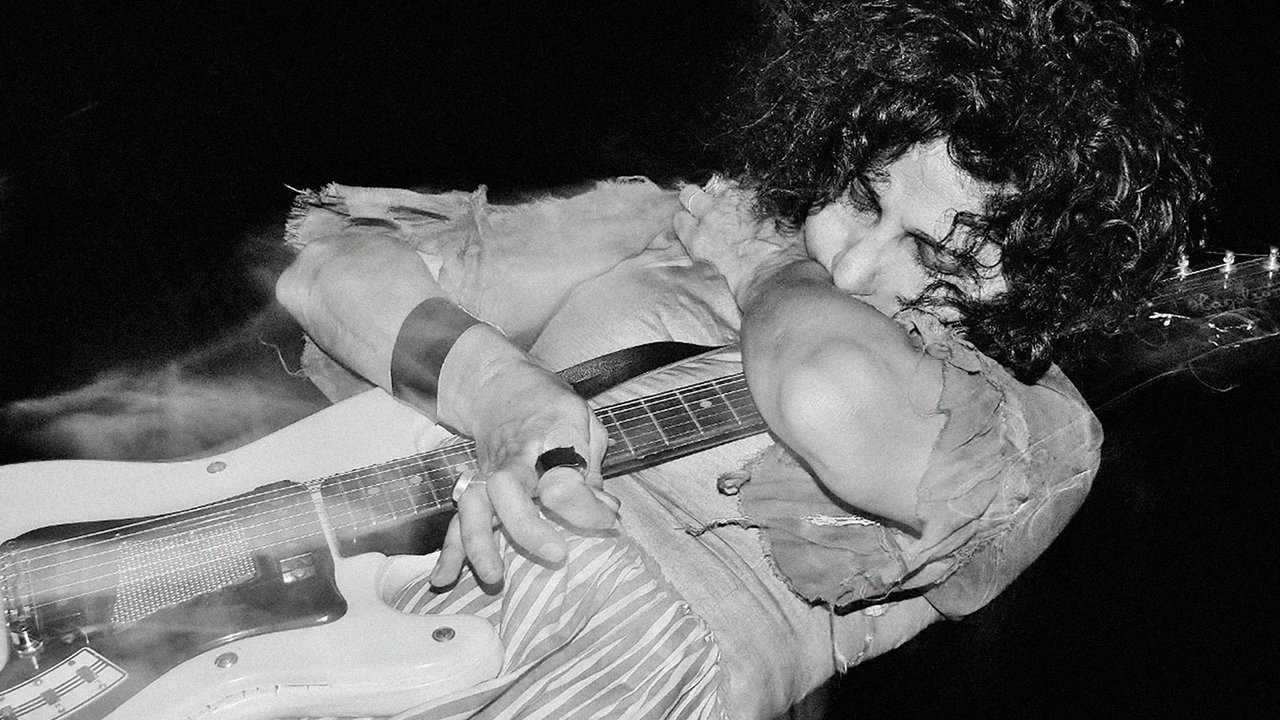

Crystal Fairy by David Goldman

Crystal Fairy by David Goldman

Teresa Suárez is sitting in the living room of her El Paso home, and she is positively electric. She usually talks quickly, but today she’s talking really quickly. She blames it on an overindulgence of caffeine (“I’ve had so much coffee that I’m sweating,” she says.), but the coffee doesn’t really account for all of Suárez’s excitement. Her new band, Crystal Fairy, is about to release its self-titled debut, and naturally, she’s over the moon.

It doesn’t hurt that Crystal Fairy also includes two of her musical heroes—Buzz Osborne and Dale Crover of the Melvins—as well as her long time collaborator, Omar Rodríguez-López of The Mars Volta, At The Drive In, Bosnian Rainbows, and 7,494 other bands. Crystal Fairy’s been decades in the making, with each of the members coming from similar backgrounds despite their disparate cultural pedigrees. Right now, Suárez is illuminating her own past.

“I was in the room when my mother was giving birth to my younger brother and I saw a lot of blood come out of her,” says Suárez, who sometimes goes by Teri Gender Bender and founded the band Le Butcherettes. “At first, the blood from the birth traumatized me,” she says, “but then, I realized it was good. It was life and it was life at its fullest. Red is the color of victory, and that’s why I usually wear it.”

The appearance of the color red has been consistent throughout Suárez’s work. She’s slathered the color across her album covers, and wears a lot of crimson in concert. She used to perform naked while covered in pig’s blood as a way to make a statement on violence against women. Her music even sounds red: songs often start sweetly, but they just as often end in ear-ringing chaos. Red is the color of love, and of anger.

Her work often focuses on the persecution of Latinx people, society’s poor treatment of women, and brutal repression—“Sold Less Than Gold” is about the international sex trade, for instance. All of this is set to music that is kinda proggy, kinda new wavey, kinda gothy—perfectly creepy garage rock.

“Teri is a force of nature,” says Buzz Osborne. Osborne first saw Le Butcherettes open for punk titan Jello Biafra, where she whipped about the stage, hissing and snarling, eventually leaping off it altogether and writhing across the floor. Excited by the performance, he told Crover that he wanted to tour with the band.

Dale Crover continues, “I went on YouTube and saw their video. I thought, ‘My God, this girl must be crazy… I was a little worried.” Little did Crover know that the Suárez on stage, the screaming, cooing, barking, yodeling demon, is quite a different person off-stage. “She’s actually shy in person. I couldn’t believe how shy she was, actually.”

In fact, the two bands were so smitten with each other that the grand finale of one leg of the Melvins/Le Butcherettes tour ended with a raucous cover of Bikini Kill’s “Rebel Girl.” Just as it seemed the Melvins had finished their hard-rumbling set, Suárez would rush onto the stage, grab the microphone, and rip into the track. The finales would often culminate with Suárez walking on top of people, mimicking that famous Iggy Pop photo, or crawling between people’s legs while swiping at their ankles.

Excited by their kinship, The Melvins and Suárez, along with the addition of Rodríguez-López, decided to record an entire album together. “Omar is a mystery,” Suárez tells me. “I’ve known him all these years and I still don’t know him. He’s guarded, and I think he’s been hurt in the past. He’ll find himself a really nice set of clothes, and then wear those clothes every single day until they are literally falling off. I’ve seen him eat and eat and eat, but he never gains a pound. He is so skinny, but he doesn’t exercise at all!”

Despite their differing cultural histories, the band members bonded over their shared life of struggle “When obstacles are thrown at my way or Omar’s way, or Buzz, or Dale, we don’t fall into that trap of being poisoned by hatred or ignorance,” Suárez says. “We’ve all been picked on or faced oppression or have had bullies. We all have different backgrounds, but we all have these things in common. We’ve been pushed around, but we can push back.”

Growing up in Denver, Colorado, the daughter of a Mexican-American mother and a Spanish-American father, Suárez’s life was embroiled in daily conflict—at school, at home, everywhere. “My father was the guard at the prison kitchen,” Suárez says. “He would check the prisoners for forks and knives on their way out. He had an accent, so his bosses would give him shit for it. He would come home, drink, and blast classical music and the Beatles. The entire house would shake from these big speakers. The neighbors would call the police, and my mother would be hysterically crying, ‘Please! No! No! That’s my husband! No arrest him! No arrest him!”

Suárez’s mother didn’t have it any easier. “My mother worked at the postal service, driving and delivering the mail,” she says. “She was sexually harassed constantly, and when she would report it, they’d be like, ‘Fill out a form…’ And this was the ‘90s! In America!”

At school, Suárez was bullied constantly because of her background. The kids would pin her against the wall between classes, knock her over, steal her lunch money, even throw her in the school sandpit. “I felt like a scab,” she says. “You pick it, you don’t let it heal—you just want to see it bleed. I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be the popular one. But, they just wouldn’t accept me. ”

One night, when she was 13, an argument with her father hit a fever pitch and Suárez stormed out of the house. While she was gone her father—the big, powerful man who would shake perps down for contraband silverware—suffered a massive heart attack and died.

“When my father died, we didn’t have the bubble that he afforded us,” Suárez says. “We had to move back to Mexico, and that was a cultural shock. People were openly misogynistic against women. At school, I had a little bit of English mannerism in my Spanish, so people would laugh at me when I spoke and call me ‘gringa’ or ‘white girl.’ It was just like before, or worse. They didn’t accept me anywhere, it seemed. So, then I decided, ‘Fuck it! I’m only going to read in Spanish. I’m only going to speak in Spanish. I’m only going to think in Spanish. My Spanish got so good that they couldn’t pick on me.”

Teenage Buzz Osborne didn’t fit in with his surroundings either. He went to high school in Montesano, a rural town in Washington state known for… not much, really. A two-hour drive from both Seattle and Portland, Montesano is remote, secluded, and wet. In school, Osborne spent his time getting drunk, committing petty vandalism, and shooting guns. “I liked all those things to a point where I am completely bored with them now,” Osborne says. “It was horrendous, and I didn’t enjoy any aspect of my teenage years.”

“It is massively frustrating that people often can’t see the things the way I see them, and it has been that way since I was a teenager,” he continues. “I thought high school was extremely boring, and I had no interest in education whatsoever. I didn’t like the people there, and I still don’t. People joke, ‘Oh, you’re just old and you don’t like teenagers because you are old.’ No, I didn’t like teenagers when I was a teenager and I don’t like them now. Actually, I generally don’t like most people in the world, no matter what age they are.”

According to Suárez, “Buzz is a very sensitive person. He tends to be somewhat guarded because, I think, he can be easily hurt by the words of other people—or, at least, the opinions of people he cares about. I think that is what makes him so special.”

While Osborne was out shooting and drinking, Crover was falling in with the “wrong crowd” a few towns over in Aberdeen. He says, “To be fair, I was one of the bad kids, I guess. For fun, we’d get fucked up. There was not much to do. We would practice all the time. I didn’t have much of a chance to do my homework. I dropped out of Weatherwax high school in ’86. Later, somebody torched the school and it burned to the ground. My school had a bunch of guys that were bullies and jerks. Just those years in general people were fuckin’ dicks.”

Together, Osborne and Crover channeled that alienation into a new form of heavy, heavy, heavy punk. Inspired by classic rock heroes like Zeppelin, Bowie, and Queen, and freaks like Throbbing Gristle, P.I.L., and Black Flag, the Melvins forged a new musical hybrid that fused the hulking riffage of the ‘70s with the sheer rage of the ‘80s. The result is an ever-evolving band that’s also mega-heavy and mega-weird. Everyone from Neurosis to Fucked Up to Nirvana to Mastodon has cited the band as an influence.

But, little did Osborne and crover know that, some 15 years after the Melvins formed, they would be influencing a teenaged Teri Suárez, who, in the ‘90s, was an outcast in the Mexican school system and was feeling more alone than ever.

“I hated where we were living in Mexico,” she says. “My friends were gone. My father died. I considered drugs or drinking, but that’s one of the things that killed my father. I didn’t want to repeat history. We finally had Internet and I looked up something like ‘bands that try.’ I found Dead Kennedys, Huggy Bear, Bikini Kill, and the Melvins. It gave me a reason to live. I would lie in my room with my headphones on and just listen to these bands. The Melvins were people with something to say, even if what they were saying wasn’t always clear. Through my headphones, in my room, I connected to them, even though I had never met them, or even had seen them, before.”

She continues, “I would have never thought that I’d be recording with them later. I could be like, ‘Yeah man, I’ve got the Melvins, I’ve got Omar…’ But, forget it. I’m in a band with the Melvins and with Omar!”

Drawn together by mutual admiration, Suárez, Osborne, Crover, and Rodríguez-López decamped to a studio and wrote and recorded an entire album in a week. With no internal mandate on what it should sound like, the group structured the sessions in a way that was similar to the famed Motown hits process: Osborne and Crover would be in one room working on riffs. Rodríguez-López would be in another working on bass lines, and Suárez would be in another, bouncing lyrics off demos that had just been tracked.

The recording sessions were so fluid that Suárez abandoned her usual writing technique. “With Le Butcherettes, I do what I call ‘the pretentious thing,’” Suárez says, adopting a posh voice, “I was sitting in the garden with my handkerchief writing about the surrealism of blah blah blah… But with this, I just let my hand do all the talking. The songs wrote and interpreted themselves.”

Drugs are something of a recurring theme on the record. One of the LP’s nastiest rockers is a tune called “Drugs on the Bus.” During the recording of another song, Suárez abruptly yelled, “My name is Crystal Fairy!” an impulsive reference to the Sebastian Silva-directed film, which is about, fittingly, a quest to find drugs.

“I don’t know about drugs,” Suárez admits. “They are good for some people. Caffeine is a drug, and I love coffee. I like to sweat. I like to detox. I would never take hallucinogenics because I’m too scared—look at Brian Wilson! I do smoke weed sometimes, but then, I only smoke in a room by myself. And sometimes even that’s too much.”

Osborne’s view is decidedly more political. “If I was in charge, I would legalize all drugs,” he says, “everything from anabolic steroids to antibiotics and everything in between. If you want to be a guinea pig for that kind of crap, you should be able to, and I don’t even think you should have to get a prescription. I don’t think the drug business is good. It’s bad. But, as long as you keep it your business, I don’t care what you do. I have no opinion until you cross the line… then, I have an opinion.”

Crystal Fairy’s debut is marked by the cohesion between the acts involved. “Moth Tongue” is built around the Melvins’ iconic lumbering riffs. As Osborne and Crover bend and twist and gnash, Suárez howls with aggression and soul. Likewise, “Bent Teeth” relies on Rodríguez-López’s penchant for complex, shifting riffs that are abrasive as they are tactical. Naturally, it fits the Melvins’ own style like a glove.

“All four of us have a shared history,” Suárez says. “We all share in a common frustration. We have had to constantly overcome obstacles that were thrown at us along the way.”

She continues, “At the end of the game, the bullies and the haters, they were their own worst enemy. We didn’t fall into the trap of being poisoned by hatred or ignorance. We pushed back in our own way.”

Suárez sets down her empty cup of coffee and for the first time since she started speaking, she pauses. She briefly looks at her coffee cup. There’s red on the cup from her lipstick. And, that red (and the lull in conversation) actually highlights the other reds in the room which were previously unremarkable. There’s red in the dishtowels, on the napkins, on the door, and here and there. Really, there’s red everywhere, you just have to know where to look for it.

—John Gentile