“Got my first guitar when I was nine years old,” Rose Moore sings on “Gypsy Wind,” a characteristically autobiographical highlight from Buckskin, her 1993 debut as Cherokee Rose. “My daddy bought it at a store in Chicago when he worked a line for the railroad.”

“Back in the day, the Postal Service used to run mail between Minneapolis and Chicago on a train,” Moore recalls. “That’s how they got the mail to Chicago from the Midwest. And [my dad] used to sort the mail on the train. They didn’t have automated sorters. They didn’t have any of that stuff. He would go there on a three-day trip and sort mail on the train all the way there, deliver it all bagged and everything, and then ride the train back. When he was in Chicago, he walked into a store and bought me a Gibson hollow-body at a pawn shop and brought it back.”

In a sense, Moore’s musical career began right then, as a nine-year-old living in Minneapolis. Unlike most kids, who get a guitar so they can learn to play songs by their favorite artists, Moore immediately started writing her own. (“Oh, I had no interest in anybody else’s music,” she admits with a laugh.) She stuck with guitar lessons just long enough to learn the building blocks that would allow her to transcribe her experiences into song. Music quickly became her diary.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“That was what really kept me going was like, ‘Oh! All this stuff that’s going on inside my head, I can actually write it down!’,” she says. “I’ve never had the patience to learn minors and fifths and all that stuff. I learned the basics. I learned, like, three chords, and I could write songs. That was it. That was enough. Just three chords, I could write a song, great. And that’s all I did for, Jesus, 20 years.”

Not once during those first 20 years as a songwriter did Moore consider recording any of her songs. She’d never even played them live in front of an audience before. It wasn’t until 1993, when her sister started dating a recording engineer named Jamie Chez, that she became convinced of their potential. Chez worked at Prince’s famed Paisley Park Studio, where he arranged for Moore to come in on nights and weekends to finally commit some of her songs to tape.

“[Jamie] heard one of my songs and said, ‘You know, you ought to try to record that song, because it’s really good,” she says. “And I was like, ‘What’s recording?’ You know? [laughs] I had no lexicon. I had no idea what he was talking about. And he goes, ‘Well, here, let me help you.’”

The Paisley Park sessions were revelatory for Moore, who had previously only ever heard her music while she performed it live in her home—just voice and acoustic guitar, no accompaniment. She recorded “I’m Not Ready” and “Sweet Fire” with Chez, and that was enough to get her hooked on the process of recording. Flanked by a team of session musicians and engineers, she pulled nine more highlights from her two-decade-long songbook, booking studio time around Minneapolis wherever and whenever she could until Buckskin was complete. The results blew her modest expectations away.

“There was an intimacy that I was able to convey when it was just me and my guitar, because that’s all I had ever done, so that was my first connection,” she says. “But hearing a full-blown production of your song? I was completely flabbergasted by how beautiful they could make it sound. And I started to really appreciate the people, the guitarists, the musicians. Even though I was too lazy to really become one, I started to really appreciate what they were bringing to my music.”

That combination of deeply intimate songwriting with fully fleshed-out arrangements and expert performances gives Buckskin its power. The album bears the DNA of Judee Sill’s psychedelic folk confessionals, Gram Parsons’s cosmic American music, the heart-rate-slowing New Age of the Pure Moods compilations (on which Moore would ultimately appear), and even some of the era’s finest pop-country songwriters like Mary Chapin Carpenter and Reba McEntire. Moore’s unflinchingly honest songwriting helps Buckskin transcend genre. Armed only with a handful of chords and her plainspoken sensibility, she consistently cuts to the bone.

Compact Disc (CD)

Moore released Buckskin under the stage name Cherokee Rose. It was a name freighted with profound meaning for Moore, who chose it to honor her indigenous heritage as well as her own strength and perseverance. In legend, the flower grew when the tears of the Cherokee who were forced West by the Indian Removal Act of 1830 mingled with the dust on the ground. For Moore, the image of something beautiful coming out of pain and hardship felt immediately relatable. As a multiethnic, multiracial child growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, she was constantly on the defensive against classmates who would constantly ask her the same casually cruel question—What are you? The stunning, almost heartbreakingly personal ballad “Black Irish Indian” was her answer to that question.

“On a very spiritual level, we are not one thing,” Moore reflects now. “We’re not pure anything, you know. It’s impossible, when you really think about it. And I try to convey that. In order for me to even be alive, there had to be a famine in Ireland that drove my great-grandparents here. Slaves had to be brought from Africa to the United States. And Indian people had to be kicked off their land and pushed westward. It’s like, all these traumatic, incredibly complex events had to occur for me to be born, and I’m just one little small person. I’m just like a speck. It’s everybody’s story, if they could only just take a look beyond what they see. It’s so incredibly complex and beautiful, you know? Really.”

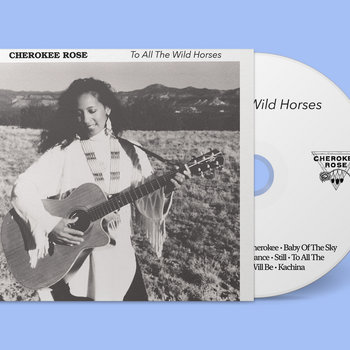

Buckskin initially didn’t make much of a splash. Pressed to a run of a couple hundred cassettes and sold exclusively at Moore’s first-ever live shows in 1993, the album came and went without many people outside of Minneapolis ever hearing it. Now, nearly 30 years later, Buckskin is being reissued on Don Giovanni Records—along with To All the Wild Horses, the sonically adventurous, stridently pro-Native follow-up that Moore completed after moving to New Mexico in 1995.

“I was instantly drawn to the music, the lyrics, and the songwriting,” Don Giovanni owner Joe Steinhardt says now of Buckskin, which was his introduction to Cherokee Rose’s music. After stumbling upon a secondhand copy of the original tape, he quickly realized that practically nobody else had heard it. “The less anyone I talked to about it was familiar with it, the more it felt like I should try to make the music more accessible. It felt like something which should be canonized.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Already, the Don Giovanni signing has earned Cherokee Rose at least one new superfan: the acclaimed indie songwriter Laura Stevenson. “I really love the uncomplicated structures and the uncomplicated use of chords, because I appreciate people who can write a good melody that’s powerful that pairs with the lyrics in a poignant way,” Stevenson says. “I think it’s really amazing if somebody can do that with the bare minimum of chords, which she talks about. And that’s something that I do, too. I learned to play the guitar to write songs, and so did she. And that’s a tool. My melodies and my lyrics are what I want to shine. She does so much with a fairly traditional use of chords, and as a songwriter I always admire that.”

Moore continued to record music throughout the ’90s and ‘00s, but more recently, her artistic focus has been on oil painting. She has a studio and gallery in Santa Fe, where she sells work on canvas as well as hand-painted jewelry. (“I make a song or I make a painting, and both of those things, they feed me in the same exact way,” she reflects. “It’s like a connection to something, and it just comes through me.”) When Steinhardt reached out about reissuing Buckskin and To All the Wild Horses—much to Moore’s surprise, she notes—she had to revisit those records for the first time in decades to approve the masters.

“I was shocked at how good they were,” she says. “I was like, ‘Oh my god! It’s really good!’ [laughs] You just are so brutal with yourself as an artist. It’s horrible. But I was surprised how good they were, and I couldn’t stop crying. I think I cried all the way through To All the Wild Horses. I couldn’t stop crying. It was just overwhelming to me.”