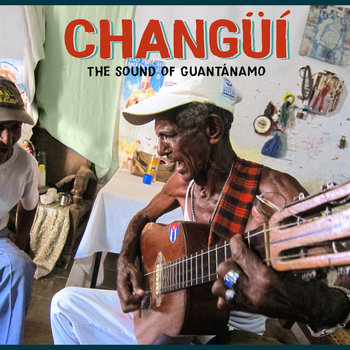

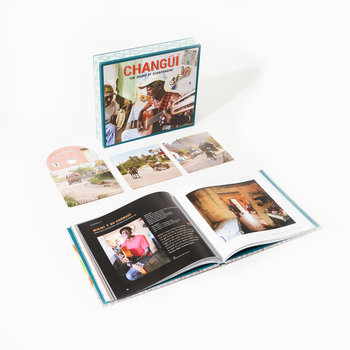

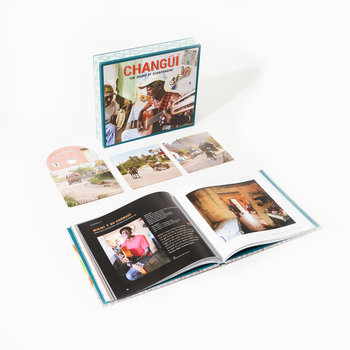

Cuban culture starts east and moves west. Or, at least, so reads an unattributed quote in the 124-page book that accompanies CHANGÜÍ – The Sound of Guantánamo, a three-disc box set celebrating a regional style unfamiliar to most listeners not from the island. The collection comprises 51 tracks, recorded by journalist Gianluca Tramontana on location along the 130-mile horseshoe road that runs west-southwest from the seatown of Baracoa to Guantánamo City, then north-northeast to the mountain villages of Yateras.

Compact Disc (CD)

Tramontana, an Italian-born, New York-based radio host and roots music fanatic who speaks a refreshingly jocular version of the Queen’s English, doesn’t remember exactly where he first encountered the east-to-west adage—only that he’s heard it often and found it to be true. “Havana is the face of Cuba, but the raw materials come from the Oriente region,” he says.

And yet, while academics trace changüí’s origin to early 19th century Baracoa—where its main vehicle, the tres guitar, was born—yateranos also lay claim to its invention. Hence, Si quieres tú bailar changüí, tienes que venir a Yateras (If you want to dance changüí, you have to come to Yateras), the refrain of a mid-collection earworm by El Guajiro y su Changüí. There is also bickering as to whether changüí deserves its own genre distinction or if it’s merely a stage of development between the older nengón and kíriba styles and the more modern son, which in turn evolved into tumba (Cuban salsa) on its westward journey to the island’s capital.

Such quibbles would make any ethnomusicologist worth his weight in ink salivate. But Tramontana, who calls himself a “recovering music journalist” in his Radio Free Brooklyn bio, says trying to parse them as an outsider would be missing the point. “To break anything down to that extent sucks the life out of it,” he says. “I’m trying not to think about music from the neck up as much as I used to.”

“Changüí means party,” Tramontana’s current catchphrase and the first chapter of the box set’s outsized booklet, sums up a more locally authentic, neck-down vision of the style. In the rural communities surrounding Guantánamo’s sugar and coffee plantations, changüí is not only a style of music and dance; it’s the festival that begins, in one town or another, every Friday evening when the workweek ends and runs until Monday morning when it starts again. Of course, changüí is both played and danced at these three-day marathons, but it was never meant to be a genre signifier. Much like “jazz,” changüí-as-genre is an arbitrary musicological notch on the continuum of what New Orleans multi-hyphenate Nicholas Payton refers to as Black American Music (“American” here referring to both continents and their surrounding islands).

It’s always suspect when “discover” is tossed around with regard to the recording or documentation of a tradition that’s existed for centuries, but Steve Rosenthal, who helped produce the compilation and whose past projects include restoration work on the Alan Lomax Archives, swears he doesn’t use the word lightly when he speaks on Tramontana’s work. “He’s showcasing a kind of music the world has really not heard outside one or two Library of Congress tracks,” Rosenthal says. “He’s letting us into a world we’ve never been a part of.”

Compact Disc (CD)

Discovery aside, Rosenthal is right that Tramontana’s collection will be a paradigm shift for many U.S. listeners. When we think of Guantánamo here, music is rarely the first thing that comes to mind. Yet despite the elevated status the infamous detention facility at Guantánamo Bay enjoys in the North American mind, Tramontana says it’s irrelevant to the life and music of most changüiseros. “Florida exists much more in the Cuban conscience than the Bay does,” he says. “It’s American soil; it may as well be a million miles away.” A track by Grupo Familia Vera late in the box set references la sardina rumbera de Caimanera (“the dancing sardine of Caimanera,” a fishing town just a few miles northeast of the army base) but said sardine never swims to the site of our military’s most public war crimes in recent memory. Changüí is not the music of politicians.

The audio quality on Changüí – The Sound of Guantánamo is spectacular, especially given the fact that Tramontana recorded each song using only his Zoom’s ambient mics and a shotgun mic. (Most recordings were taken outdoors and in the midst of extreme revelry, to boot.) He reserved the shotgun for the behind-the-beat baseline of the plucked-box, microtonal marímbula, while the Zoom’s X and Y mics captured every other sound: polyrhythms slapped through bongo cowhides; steady cha-cha-chas stroked into the güiro and the guayo; cheeky guajeos finger-picked on the tres; and, of course, voices uplifted in song.

It’s a shame that, due to the ripple effects of a 60-year U.S. embargo on Cuba, the actual musicians who played on this project are unable to speak to the outside world about their work. Their voices should clearly be at the center of this collection’s narrative. On the bright side, Tramontana seems unequivocally dedicated to telling their stories as best he can. He waxes poetic when he talks about the changüí universe. Three-minute standards expand to hour-long jams as partygoers improvise on familiar forms. Rum miraculously manifests at parched family reunions, facilitating transcendent moments of cross-generational connection. Ancient masters live out their last days in remote forest shacks. And “hot-shot tres players” bring their young children to changüisas in the mountains, inspiring the next generation of changüiseros. “The changüí life is like the gangster life,” Tramontana says. “You’re born into it.”