“I’m not seeking out presidents or heroes or something like that. I’m really interested in everyday folks.”

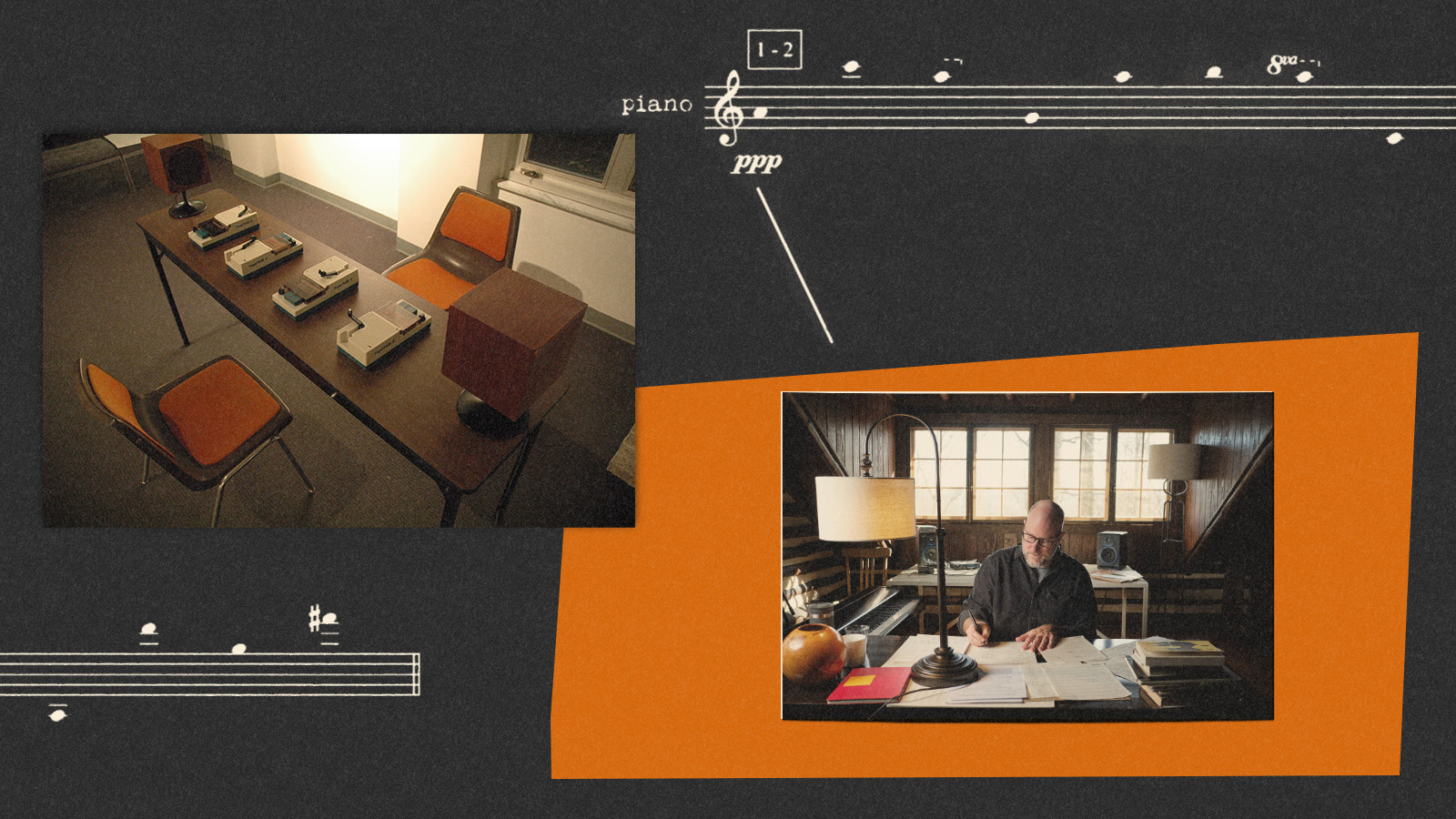

Brian Harnetty is talking over Zoom about the subject of his work: ordinary people. It’s fair to call Harnetty a composer, because he writes music for himself and others to play. But Harnetty is both more specific and more expansive when describing his practice, calling himself “an interdisciplinary sound artist who uses listening to foster social change.” He works with sound archives, recordings of interviews and people telling stories about their lives—the places they lived, their memories. He listens to these recordings, then writes chamber music to accompany them. At the center are, indeed, ordinary people, most of whom are never even identified, but whose stories and reminiscences are each pieces in the complex puzzle of Appalachian Ohio, fragments that fill in a picture of the physical, social, and historical fabric of the region: ecology, economy, myths, and legends.

“Sometimes I call it archival performances, but that feels a little too fancy,” Harnetty says. “When I’m writing about it, I define it as a kind of interpretation of archival materials.” His method puts a frame of new music around audio from the past, turning a piece of archival audio into a listening object, while the music connects the present day listener to a voice that is likely gone—a ghost speaking from the past, the present making music with it.

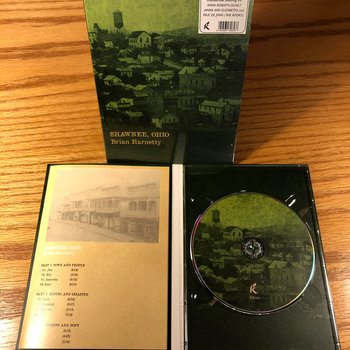

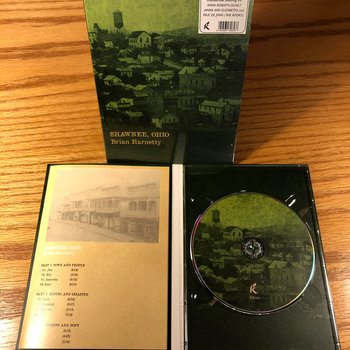

Compact Disc (CD)

Harnetty tells his own story: “When it started for me, 20-odd years ago, I was a grad student in the UK, studying with Michael Finnissy,” an English composer known for his large-scale and incredibly complex works. “He’s very well known for using musical borrowing from all types of folk music, from around the world. I was very enamored with that process, and of course, there’s a long, long history of musical borrowing.

“When I came back to the U.S., I flipped that over into sampling, as opposed to notated scores. And it felt very liberating at first. Like, I could use whatever I wanted, but then all kinds of ethical questions came up…basically, should I even be using this material? And if I do, what kind of relationship should I have with both archives and the communities that are connected to the recordings? I was working through a lot of the Harry Smith anthology and trying to figure out ‘Old Weird America’ and how I could find my own voice somewhere in there. That, alongside the ethical questions, led to a more formal relationship with archives.”

That began with a fellowship at the Berea Sound Archives, “and it just completely changed everything for me,” Harnetty says. “There, a recording was no longer this inanimate object, and archives could seemingly contain everything, except for those living interactions with people. I knew that there was a kind of archival stewardship happening that I really had to pay attention to. And so it changed the way I composed. I stopped cutting things up a bunch and letting longer passages go and trying to leave it to get a sense of leaving things intact.”

Some of that composing means harmonizing someone singing, but usually it means making a kind of soundtrack to a story, like the ones collected on Rawhead & Bloodybones, where Harnetty adds music to recordings of folk tales from Appalachia made in the 1940s.

Those stories are part of the culture of Appalachia, while the ones on Shawnee, Ohio are about a place and the people who lived there, the eleven subjects each talking about what life was like in this coal mining town:

“I often look for in-between moments,” Harnetty explains. “Fragments that would normally be edited out in a commercial recording, I’m drawn to those. I’m also drawn to the grain of not only the voices but also the material of the medium as well. Tape hiss, for example, or the warbling of age and all that stuff is very interesting to me. And then there’s also a phrase that I find amusing all the time, from psychologists: ‘A text conceals and speech reveals.’ Speech has all of this additional information layered into it. So, if I listen long enough, I can imagine that I’m hearing nervousness or vulnerability or confidence or uncertainty, and those emotional states. When I hear those things, that is the gold that I’m seeking.”

Harnetty’s focus is not solely on the historical and cultural context of ordinary people. He’s used the Sun Ra/El Saturn Archives at the Experimental Sound Studio to make a 7-inch, and his most recent project, Words and Silences, is about Trappist monk and writer Thomas Merton, and uses audio from the Thomas Merton Collection at Bellarmine University in Kentucky. In 1967, Merton bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and started recording his own thoughts, using this as a part of his contemplative practice. Along with Merton’s own archives, Harnetty “went through all the music that [Merton] listened to throughout his life, which had already been already been documented by other scholars,” he says. “And I made transcriptions of small passages that I enjoyed out of that, everything from John Coltrane to early Kansas City jazz and some folk tunes. It’s unrecognizable in the music” that Harnetty adds to Merton’s voice, “but there’s something that’s related to the subject.”

Compact Disc (CD)

Harnetty describes growing up Catholic in Ohio, and reading Merton both with fascination and as a means to “gently argue” with his parents. Then, in 2017, he “happened to be in Louisville and went to the Merton center, and had arranged to listen to some recordings. And I wasn’t really finding anything that I thought sounded good to me. It was interesting, but it’s all public facing and outward. And then the archivist there pointed me to these tapes that he made in solitude on his own recorder in the spring of 1967. I don’t think [Merton] knew what he was going to say. He was just exploring all kinds of books that he was reading—Sufi mystics, Michel Foucault, Samuel Beckett. He was doing, like, experimental jazz meditations on the night that there were racial protests in Louisville. And I could tell right away that I could hear the exact things that I was talking about earlier, the in-between sounds, those sorts of things. You can hear him questioning what tape means, and thinking that through.”

Book/Magazine, Compact Disc (CD)

Talking with Harnetty about how his work engages with the past, he brings up his own. “I had just planned on staying either in the UK or Europe,” he explains. “But Michael said, ‘Maybe there’s something you need to figure out at home. There’s some kind of story that you need to push. You can always come back, but maybe you should investigate that.’ So it was kind of a dare almost, you know, to come home when I had planned on before that ‘I’m getting out here.’ And I did it, and then I’ve been doubling down on that for the past 20 odd years.

“I think that the style that I’ve continued to use is a reflection of those experiences,” he goes on. “I mean, it reflects not only whatever the landscape is but also my audiences. I referenced music that people play over the decades there, or that might be familiar to people with places or whatever.” At the heart of his idea, he says, “is the idea of place. I mean, there’s some pretty extraordinary people here.”