In the late 1980s, British Hammond organ maestro Brian Auger became known as ‘The Godfather of Acid Jazz’ thanks to albums from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s with his groups The Trinity (with singer Julie Driscoll) and Oblivion Express. Lauded by groups such as The Brand New Heavies and The James Taylor Quartet, his own musical journey began less by inspiration than by imitation. “My dad had a Kastner Pianola—a self-playing piano,” says Auger of his childhood in West London, “and from the age of about four I was fascinated by this thing. It was run by air and a pair of pedals. And basically, I would see the notes play, and then follow what I heard.”

It was his older brother who first introduced Auger to jazz. “He would collect all these jazz records on 78 and I got to listen to all sorts of things—Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory,” Auger recalls. “Then when I was about 10 he gave me this huge radio. I rigged up an antenna out of the bedroom window and was going around the stations in the middle of the night, and all of a sudden this voice announced: ‘This is the American Forces Network in Germany. We present: The Jazz Hour.’ And that was like heaven to me.”

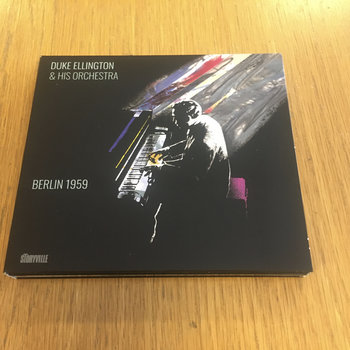

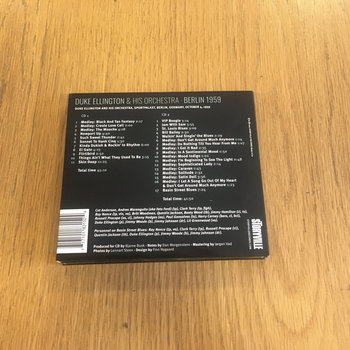

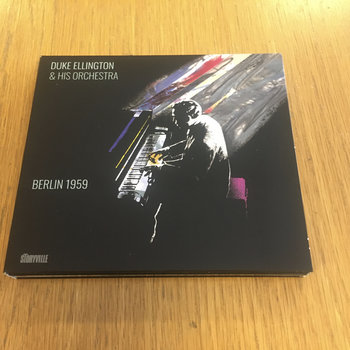

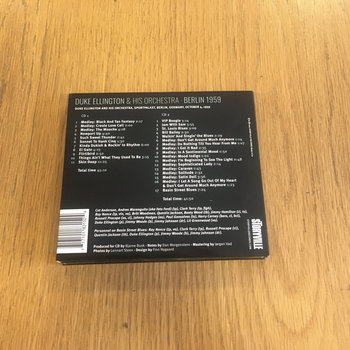

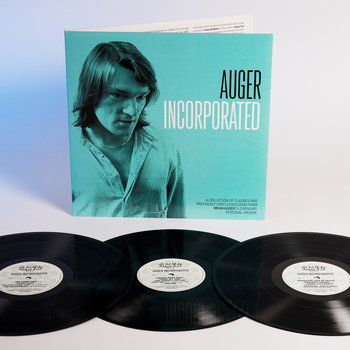

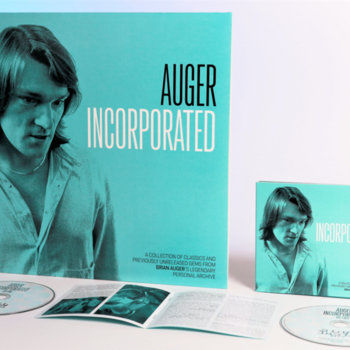

Compact Disc (CD)

Through the radio, Auger was introduced to then-contemporary American jazz. “The first thing I heard that really socked it to me, in terms of being a budding piano player was Oscar Peterson’s ‘Tenderly,’” he recalls. “When that guy started to swing, when I heard his technique, I was like ‘Oh my God I want to play like that.’ That was the first record that really spurred all of this. I began to look for the pianists—I used to bombard my local record shop, WG Stores in Shepherd’s Bush Market, and ask them if they had this stuff.”

Upon his return to West London—he’d spent two years living with a family in the North of England after being evacuated during WWII—Auger found that his school friends were hip to the sounds of American bop. “They said to me, ‘Have you heard The Jazz Messengers?’ and I was like, ‘No who is that?’,” says Auger. “Hearing the piano of Horace Silver was a whole new thing, and I was like ‘That is how I want to play.’ So I learned his tunes and after a few years, I joined a band that was playing Jazz Messengers material. And it went on from there.”

Appearing in pubs across the capital, Auger caught the attention of influential figures on the London jazz scene. “I got a call one day from a tenor saxophone player by the name of Jimmy Skidmore who was part of the jazz scene that came out of the clubs of the day, like [legendary Soho jazz hangout] The Flamingo,” Auger recalls. In addition to playing with Skidmore and vibes player Dave Morse’s Quintet, Auger also launched his own trio at The Flamingo featuring Rick Laird on upright bass and Phil Kinorra on drums. “Starting as a trio at the Flamingo was a real eye opener,” says Auger. “We played with most of the guys on the scene—Tubby Hayes, Ronnie Scott, and all sorts of people. They would call me and say they wanted a piano trio to open for someone, and that really started the ball rolling for me as a serious jazz musician.”

By the early ‘60s, weekends at The Flamingo had been taken over by infamous promoters Rik and Johnny Gunnell, whose Friday and Saturday all-nighters became the stuff of Soho club legend. “These guys started putting on bands like Georgie Fame & The Blue Flames, Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, The Chessmen, Graham Bond, and Chris Farlowe—tons of these R&B bands,” says Auger. “Rik Gunnell used to book my piano trio for the all nighters, but he always used to be on at me about getting an organ. I was like ‘How dare you suggest such a thing?! I’m a jazz piano player!!’”

But one day, walking past his local record shop, Auger heard a sound that stopped him in his tracks. “I was like ‘What the hell man?’ I had never heard anything like it,” he says. “So I walked in and asked ‘What is this?’ and they showed me the cover. It was Jimmy Smith’s Back At the Chicken Shack,” Auger recalls. “The only other organ I’d heard at that point was the theatre one up in Blackpool Tower, when this big Wurlitzer would play ‘The Dam Buster’s March’ or something. The sounds of these organs were so foreign to playing jazz. So when I first heard Jimmy Smith, I really couldn’t figure out what this was. When I discovered that it was actually a Hammond organ he was playing, I went ‘Oh my goodness.’”

One night Auger got a call from Rik Gunnell to say that Georgie Fame had been taken to the hospital with sunstroke. Could he stand in for him at the famous Roaring ’20s night in Soho? “When I got there I said ‘Where’s the piano?’ And they said, ‘There is no piano. That’s Georgie’s organ over there, you’re playing that,’” Auger recalls. “I looked at this Hammond M100 organ with this array of switches, knobs, and dials, and thought, ‘Don’t panic, just try and make it sound as close to Jimmy Smith as you can.’ So that’s what I did. I remember coming off the stage dripping in sweat and one of the regular guys came up and said, ‘I didn’t know you played organ Brian! How long have you been playing organ?’ And I said, ‘About 45 minutes.’ So that was my introduction to the Hammond organ. And I took to it straight away.”

Auger bought himself a Hammond L organ, but he couldn’t get the sound he’d heard on those Jimmy Smith records. “A lot of musicians used to go to New York, and we would give them lists of records [to buy for us while they were there],” Auger says. “So I told them, ‘Anything with an organ on it.’ One of the guys turned up with an album by Jimmy McGriff, and on the front cover of this LP, Live at the Apollo, there was a picture of him on this great big Hammond B-3. So I went directly to the company and said ‘I need one of these.’”

Originally a self-confessed jazz snob who looked down on rock and blues, Auger was converted after playing sessions with The Yardbirds alongside Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck. “There was so much jamming going on in the ‘60s that I completely changed my outlook,” he says. “It taught me a big lesson, and I began to look at all the amazing creative bands that were coming out and quickly got over my jazz snobbism.”.

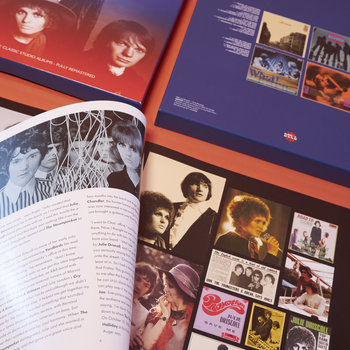

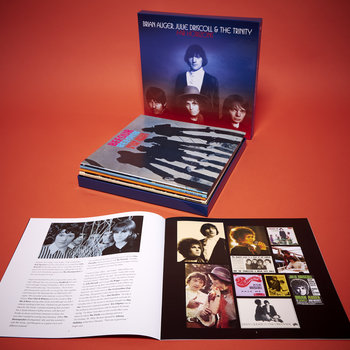

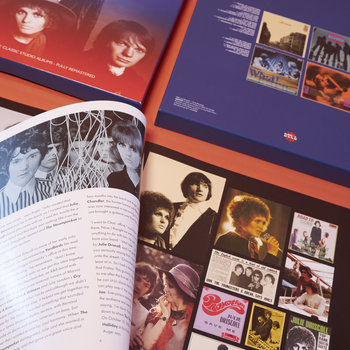

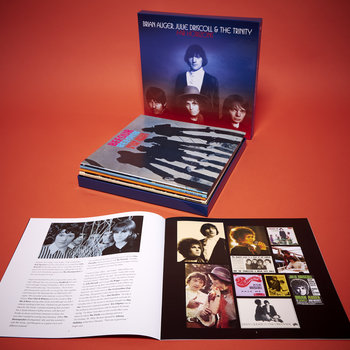

Vinyl Box Set, Compact Disc (CD)

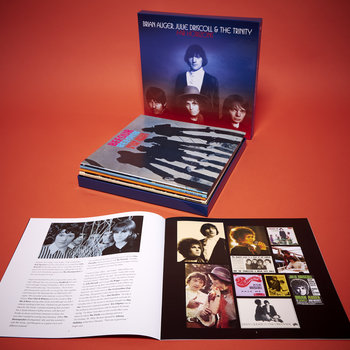

In 1965, after a short run with an organ trio version of The Trinity with Rick Brown on bass and Micky Waller on drums, Auger formed The Steampacket with vocalist Long John Baldry, a then-unknown Rod Stewart, and a young mod singer by the name of Julie Driscoll. Playing everything from Chicago blues to gospel, along with Jimmy Smith numbers, gave Auger the space to develop the techniques he needed to master the Hammond B-3. After two years the group fell apart—but not before cementing Auger’s musical partnership with one of the great jazz and pop singers of the ‘60s. “Because I’d been playing across this huge spectrum of music I had a good idea that I wanted my own band to reflect all these different feels,” says Auger. “I knew what I wanted was a funk rhythm section overlaid by what I was doing with jazz, and then a singer with a lot of soul. And that turned out to be the great Julie Driscoll. Boy.”

The new incarnation of The Trinity—with Driscoll on vocals and playing heady fusion of jazz, pop, R&B, and psychedelia—entered the studio in 1967, just as the psychedelic sounds of America’s West Coast were flooding into the UK. “It was around the time of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco and the Monterey Pop Festival, and we’d seen and heard all that,” says Auger. With the help of a 17-year-old engineer called Eddy Offord (who went on to work with Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer) the group began to experiment with their sound. “I came into the studio, and Eddy had this shoebox-sized thing he had made with a great big knob on the front,” Auger says. “He said to me, ‘Hey Brian do you want to listen to this?’ And I said, ‘What on earth is it?’ He replied, ‘It’s a phaser, let me put it on the strings.’ And he put it on and turned the knob, and I went, ‘Oh my god, keep that in.’”

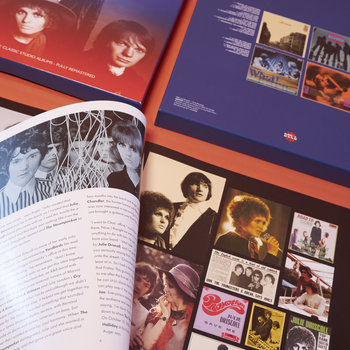

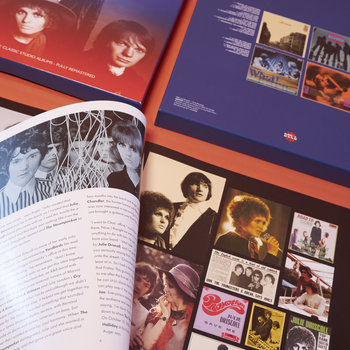

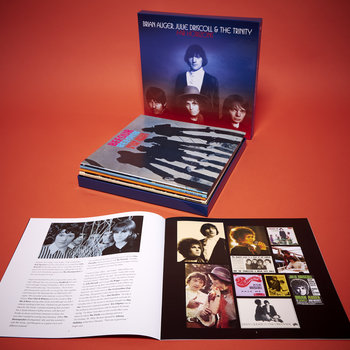

Between 1967 and 1969, the group released a series of mind-melting LPs for the Marmalade label, including Open, Definitely What!, and a trio of albums under the name Streetnoise. The latter spawned the psychedelic jazz future club classic ‘Indian Rope Man’ and the group’s biggest hit, a cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’. “We had first heard that song through these tapes that came over from America [which would later become The Basement Tapes],” says Auger. “Julie would pick these tunes to sing, and ‘This Wheels on Fire’ was one of them. I thought we could make something of it. But it was too fast, so I thought, ‘Let’s slow it down and make it mysterious,’ because the psychedelic situation was going on. And when Julie put down that vocal, she really killed it.”

Vinyl, Compact Disc (CD)

Driscoll, Auger, and The Trinity toured the U.S.—even appearing on American TV as guests of The Monkees. Driscoll was a style icon for the late ‘60s, whose face became as famous as her voice. Ultimately, the constant press attention on Driscoll, as well as tussles between the members’ individual managers, caused the group to spilt soon after their 1970 LP Befour. After marrying jazz pianist Keith Tippett the same year, Julie Tippetts went on to become a renowned improv jazz singer who remains prolific today.

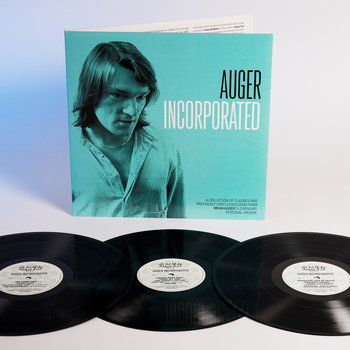

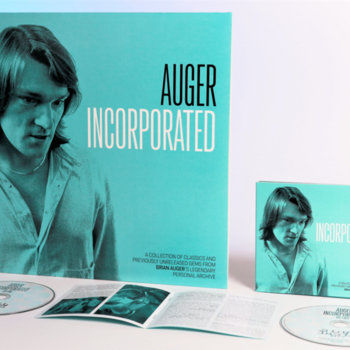

With Julie Tippetts pursuing the avant-garde end of jazz, Brian Auger re-assessed his own musical direction. “My aim was to build a bridge between the separate scenes of rock and jazz and everything in between,” he says. “It really was me wanting to create something that would lead people wherever they wanted to go,” Auger says. “I wanted to develop this idea [of fusion music], but thought maybe I was pushing against the commercial tide. I thought ‘Maybe this is the quickest way to oblivion.’ And that was the beginning of Oblivion Express.”

Between 1971 and 1977, Brian Auger’s Oblivion Express (with members that included Barry Dean and Clive Chapman on bass, Jim Mullen and Jack Mills on guitar, Robbie McIntosh and Godfrey MacLean on drums, Alex Lingertwood on vocals, and Lennox Langton on congas) released nine LPs of prescient jazz-rock fusion that would find a new audience many years later.

Vinyl Box Set, Compact Disc (CD)

It was the late ‘80s when Auger discovered that a new generation of UK clubgoers were listening to Oblivion Express. “I found out there was a label actually called Acid Jazz,” he says. “When I finally met the owner, Eddie Piller, he said, ‘Don’t you realize the template for Acid Jazz was the Oblivion Express album Closer To It?” At the same time, records like “Indian Rope Man” that hailed from the freakier end of Auger’s catalog with The Trinity were becoming classics on the jazz dance floors in the UK. Auger would soon be sampled by everyone from Yasiin Bey—who used bits of Oblivion Express’s version of “Maiden Voyage” on “If You Can Huh! You Can Hear”—to Madlib, who used 1971’s “The Sword” on “Paradies” from his 2014 album Rock Konducta Pt. 1 & 2.

Now based in Los Angeles, Auger steered Oblivion Express into the ‘00s with LPs like Looking Into the Eye of the World, and a band that features his son Karma on drums and daughter Savannah on vocals. “I’m not touring Oblivion Express right now because of the pandemic,” Auger says. “But that quiet period gave me some time in which to really hear music. And you need that sometimes.”

Released in late summer and early autumn, the two box sets of music by The Trinity and Oblivion Express—which feature classics alongside never-before-heard takes—have also given Auger much to contemplate. “The job that [label] Soul Bank has done on this is tremendous, and I’m very happy this is coming out,” he says. “I’ve been completely blown away by hearing all this again. It’s given me a real shot in the arm about my own music.”