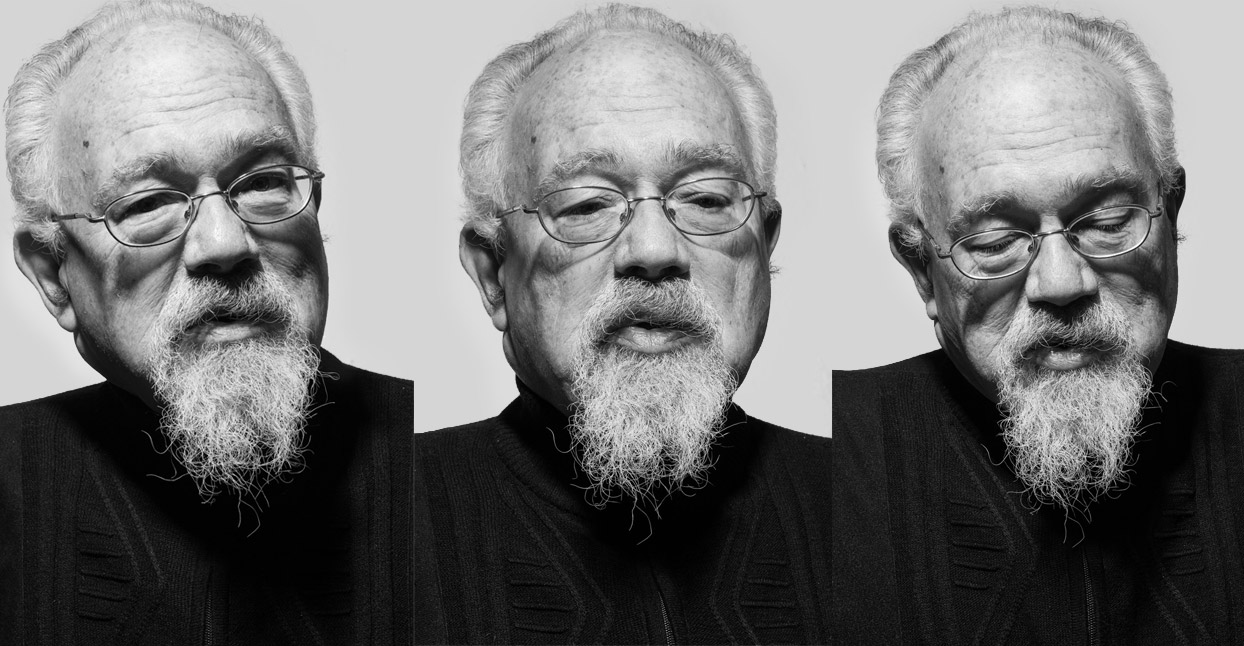

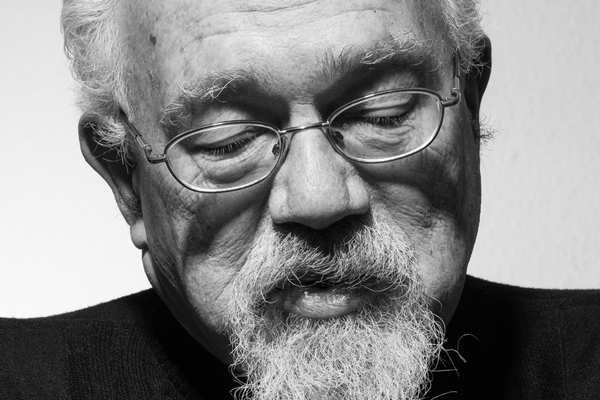

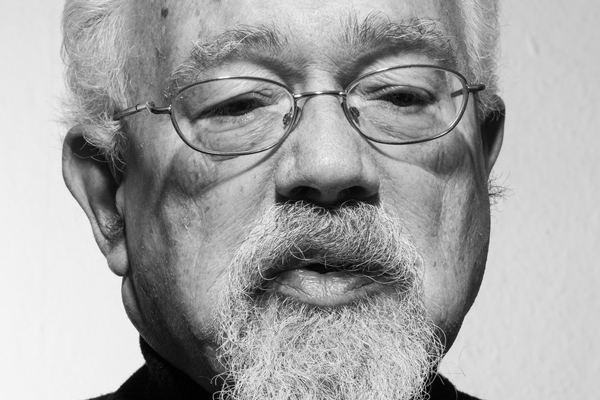

“Living Euro to Euro, sleeping on the couches and extra beds of friends, a man without a country and a post office box in New Orleans for a permanent address.” That’s how spoken word poet John Sinclair describes himself in one of the passages on Beatnik Youth, his new collaboration with producer/multi-media artist Youth, who plays bass in Killing Joke and has worked with artists like The Orb, The Verve, Beth Orton, and Crowded House.

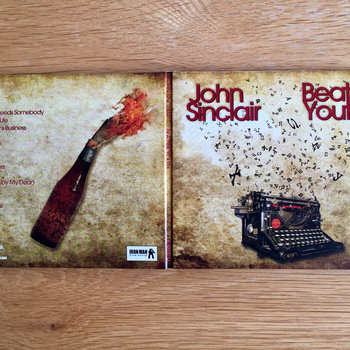

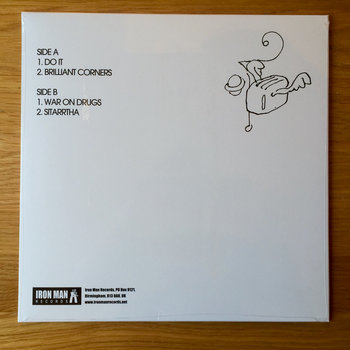

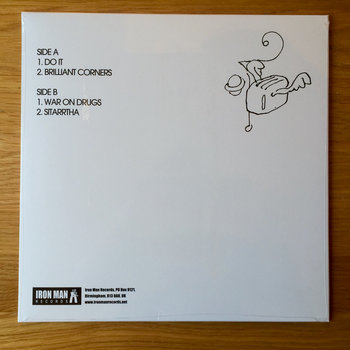

Out as a double-CD on September 8, Beatnik Youth is preceded by Beatnik Youth Ambient, a vinyl mini-version of the album containing two of the more spacious selections and two non-LP tracks; the selections range from raucous rock ‘n’ roll to psychedelic jazz and abstract soundscapes. Throughout, Sinclair’s booming voice functions as an anchor, taking on an American social landscape bursting with civil unrest and self-reinvention as Youth’s modernist production swirls around him.

Immortalized by John Lennon’s 1972 song that bears his name, Sinclair is an iconic figure of ‘60s counterculture, famous for, among other things, having co-founded the anti-racist White Panther Party and for managing Detroit’s legendary leftist proto-punk outfit MC5 early in its history. Following a highly publicized two-year stint in prison for marijuana possession (Lennon’s song was a protest against his incarceration), Sinclair has stuck to his guns as an advocate for marijuana reform.

Over the last 13 years, however, he has focused primarily on his other two passions, jazz and radio, delivering a weekly online show on the Radio Free Amsterdam network in spite of his itinerant status. As he says on Beatnik Youth, the Flint, Michigan-area native maintains no fixed address, splitting his time between Amsterdam, New Orleans, and Detroit, staying in the Netherlands for three months at a time as visa restrictions dictate.

Compact Disc (CD)

By turns nostalgic and irreverent—a passing anecdote about Allen Ginsberg introducing Thelonious Monk to LSD stands out as either crass or hilarious (or both!) depending on your point of view—Beatnik Youth is both a love letter to a bygone era and a forceful call for America to come to face its own conscience. “There is something about the American mind—set on destruction, relentless, unpenitent…,” Sinclair says on the album.

In separate conversations, we caught up with both Sinclair and Youth (real name: Martin Glover) for what turned out to be surprisingly lighthearted exchanges, with Sinclair’s Elmer Fudd-esque laugh smothering the background clatter of an Amsterdam café.

What kind of career trajectory did your parents expect for you?

John Sinclair: They wanted me to be a lawyer.

And how did they react when you took the path you took?

Sinclair: They were quite puzzled. But the first time that I got busted for weed, in October of 1964—I was a graduate student at Wayne State University in Detroit; I got busted selling some weed to an undercover officer—I was arraigned in Detroit Recorder’s Court the next morning, and my parents came from Davison to bail me out of jail. They sat in the courtroom waiting for my case to be called, and there was this procession of characters—drunks, prostitutes [today’s preferred term is “sex workers” —ed.], ne’er-do-wells, and the judges, guards, and lawyers that serviced them—and this just shocked the living hell out of my parents. They were Republicans. You could have never told them that anything like this existed. So at that point, they realized where I was coming from. Maybe they didn’t agree with everything I was thinking and saying and doing [laughs], but they saw where I was coming from. From then on they were supportive of me, even when I was in prison—or I should say, especially while I was in prison.

One presumes that not much of your hometown Davison is still left the way you remember it.

Sinclair: Well, it’s still just a little bitty town. They just keep adding subdivisions onto it. I remember when they added the first one, when I was in school. But they’ve still got the two-block main street, the corner with the four gas stations, the one theater, one hotel that has the only bar—you know, little town, Midwest.

So it’s still fairly intact then?

Sinclair: Oh yeah [laughs]. That’s an interesting way of putting it—it’s frozen. Although, the last time I was there last year, I went to make a guest appearance at a marijuana dispensary located kitty-corner from where I went to school. It was a very exciting event for me [laughs]. I write for a medical marijuana magazine in Michigan—prosaically enough, it’s named Michigan Medical Marijuana Report, or MMM Report. They arranged for me to make a personal visit to this dispensary and spend the day there. So I just sat there and laughed all day watching people in my hometown come in and out buying weed. It was kicks.

How many of them did you recognize?

Sinclair: None. I left there in 1959. That was a long time ago! [Laughs] If there was anybody I knew, I wouldn’t recognize ‘em. None of us look like we did in 1959.

It’d be kinda funny if the town gave you an honorary—

Sinclair: —Not gonna happen! They won’t even recognize [Flint native and documentary filmmaker] Michael Moore and he’s a millionaire. I’m a pauper, so I’m doubly despised [laughs].

How much do you ever get hassled at customs coming back into the States?

Sinclair: Very little, knock on wood. I used to get hassled a lot in Detroit, but then they legalized medical marijuana in 2008. I’m a patient now. I got a card and they stopped harassing me.

When you first went to the Netherlands, what did you struggle with, and how did you adjust?

Sinclair: Struggle? [laughs] There was no struggle. I adjusted right away—I stopped being afraid of being held up on the street or shot by accident. I got used to not having to worry about the police. I could buy weed over the counter. I was walking around in a beautiful area and there was brilliant public transportation. I fit in like fingers in a glove on a January day.

How did you connect with Youth?

Sinclair: I did some stuff in London with a band called The Dirty Strangers, headed by a guy named Alan Clayton. His manager was a guy named Ian Grant who, it turns out, had been a White Panther under Mick Farren when he was 16. He picked up the MC5 at the airport for the Phun City Festival [a 1970 rock festival at London’s Hyde Park that Farren organized —ed.]. So we bonded right away [laughs]. He also used to manage that band Big Country. He had bought the name Track Records out of bankruptcy. Jimi Hendrix’s first single ‘Hey Joe’ and The Who’s early albums were on Track Records. [It was actually the Hendrix Experience’s second U.K. single “Purple Haze”; the label was co-founded by early Who managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp. —ed.] They were very important in England. Of course, Ian didn’t get any of the Hendrix or Who masters. He just, out of nostalgia, thought that was a good name for a record company. But anyway he did this series of concerts where I performed with The Dirty Strangers.

Youth’s duo, Zodiac Youth, was on the bill. Youth and I met backstage and we hit it off. I liked him a lot. He said, ‘You know, I’m a producer and I’ve always wanted to make a jazz and poetry record.’ And I said, ‘You know, you’ve just met the right guy!’ Ian Grant helped nurse it through. We did it on a totally speculative basis. Youth was doing some pedagogical work at Kingston University at the time, so we went there and did a session for nothing, brought a bunch of guys in who were friends.

For the rest, I went to his house across the river. Youth had his little studio in the front room. Michael Rendall was the engineer and also played keyboards. They would play me music they had devised, and I would pick poems that I thought went well with that music and record ‘em. Then they would add things and remix them and all that. It was really exciting. I’d never done a session like that before. I usually perform live with a band and somebody records it. I loved Youth’s music, and Michael could play really well and had huge ears. So it was the three of us working together over the board. It was very creative. I really enjoyed it. They had some musical settings for poems of mine that I thought made them sound really good. And then they took some of the live stuff and mixed it in. They created this thing. I was just the poet [laughs]. Usually I have to produce, too, but I just stayed out of their way. I was so charged about this thing coming out because I was really happy with it. And then it all went to nothing when Track went out of business again. I did another record with Mark Sampson at Iron Man Records and was bemoaning the fate of this and he said, ‘I’d like to put it out.’ So he got together with Youth and they put together the LP version. I’m telling you, I’m so happy with this as an artistic piece of work.

Vinyl LP

On the track ‘Do It,’ you talk about being creative with no expectation of getting paid or having an audience. But the MC5 ultimately did have an audience—

Sinclair: —and then they fired me. We never had a contract, so whatever money came to them never came to me ‘cus I was in prison [laughs].

What did that experience teach you about the intersection of art and commerce?

Sinclair: Be more careful—get a contract! [Laughs]

During the two years you were with them, how were you able to reconcile their commercial and career goals with your political beliefs and non-material lifestyle?

Sinclair: Well, I didn’t have any career goals, personally. I was in thrall to the MC5, and I wanted them to achieve whatever success that they were capable of achieving. And I thought, with the nature of what we were doing, that it was perfectly appropriate to operate through the world of commercial music because that’s where the audience was. And also because it would produce revenue to make it possible to carry on our struggle on other fronts, as we were becoming more and more interested in doing. So I didn’t feel any contradiction. But whatever career I had as a manager ended when I went to prison in July of 1969. When I got out at the end of ‘71, it was a whole different world as far as the music business—culture, the whole thing had changed. They’d had Woodstock and then everything had been taken over by the major record companies. So they transformed what we were doing in the ‘60s into a whole different world, which still prevails. I worked with music locally—I managed bands, booked concerts and clubs, and did all kinds of things to stay with the music. But it wasn’t ever focused again on trying to break somebody out or work on a national scale. I didn’t really care about that.

What’s your take on revolutionary music and the kind of impact it can have?

Sinclair: Oh, I don’t know. I don’t even think like that anymore. I thought 50 years ago that you could make a big difference, but really we couldn’t. And they bought it off. I look at popular music as one of the principal means of mind control and exploitation that they have. It’s an integral part of keeping this shit as fucked up as it is. And it gets worse and worse. So I don’t really have any thoughts about that. I just think of the stuff I do with music as a creative outlet for people that have an imagination and musical taste who want to say something about how they feel and think. Perhaps this stuff will make them reach out to other people who feel the same way and that’ll make them feel good about it. You know, art [laughs].

How do you feel about the way the MC5 are remembered?

Sinclair: I feel good about it, except that the same creeps that kept them from ever making any money won’t even let them into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, even though the majority of them are already dead. I imagine when Wayne [Kramer] passes, they’ll let them in—as if that means something, but that’s the construct. Mitch Ryder, the guy who invented rock ‘n’ roll in America in the ‘60s, isn’t in there either. [Laughs] That burns me.

Black music—rhythm and blues and jazz—were hugely influential on you as a kid. What do you think about the way jazz is presented as high art now, like it belongs in a museum?

Sinclair: Well, I happen to think jazz is high art.

I mean high-brow art.

Sinclair: The music media, they don’t tell anybody. They don’t play any jazz. Americans don’t know who Miles Davis was. That’s a sick situation. What’s going to come in the wake of that? I lost my interest in popular music by 1975, except for Philadelphia International, Stevie Wonder, and Curtis Mayfield. That’s why it’s important to listen to the real music that people like that made. Now it’s considered historical, like classical music, but it’s still good. It sounds so much better against the backdrop of today even than it did when it was first made. Charlie Parker sounds better in 2017 than in 1947, I think.

What’s the closest you’ve ever come to being co-opted?

Sinclair: Never! People say, ‘Man, we’re so proud of you. You never sold out.’ And I say, ‘They never offered me anything.’ [Laughs] I don’t know what I would’ve done! Fortunately, I was spared that moral dilemma. In a way, I was lucky, because I got busted for weed when I was about 23 years old. The first story that ever appeared about me in the media said ‘Would-Be Schoolteacher Defends Marijuana Habit.’ So I never had to be afraid of being outed. They put me right out on Front Street.

How much can art and commerce overlap in a way that’s humane?

Sinclair: I don’t know, but it happens by the accidents of capitalism. In the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, popular music was good music. But I don’t think about these things much anymore. It’s too big.

Your circle of ‘60s radicals rejected the mainstream press. But these days you read the New York Times and the Detroit Free Press. What is the value you get from mainstream outlets like the Times?

Sinclair: I don’t watch TV, so I get the headlines on the Internet. But I just like reading papers. I’ve been reading the paper since I was three years old. I also like to do the crossword puzzle and I like the funny papers [laughs]. And I started following the business news when the Enron story broke. I realized that the New York Times business section was actually the crime section. If you followed that, you could see what was going to happen and who was going to do it. It’s fascinating to me. Now I’m following all this stuff around [Trump]. If it wasn’t so ugly, it would be hilarious!

When did you, Youth, first become aware of who John Sinclair was?

Youth: I’d heard about him through the MC5, the whole countercultural movements in the ‘60s, and his use of slogans, like ‘If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.’ [This is a riff on an Eldridge Cleaver quote that the MC5’s “spiritual advisor” Brother J.C. Crawford says to the audience in the introduction of the band’s album Kick Out the Jams; Sinclair also popularized the slogan “Rock and Roll, Dope, and Fucking in the Streets.” —ed.] I didn’t know about the John Lennon benefit at the time it happened, but I read about it later. I wasn’t really aware of John’s poetry, but I used to share a flat with Kris Needs, who’s a music journalist and a Stones aficionado. He used to talk about John a lot and what he achieved. He gave me a good education. And also from the White Panthers. I’ve been working on a book, Freak Philosophy, for a long time with people I’ve interviewed over the years who were a big inspiration to me. I’ve got everyone from Terence McKenna to Chet Helms to John. I wanted to meet John as part of that as well.

You also do poetry of your own. What kind of influence has Beat culture had on you?

Youth: Oh, [it’s been] massive—from Burroughs’s cut-up techniques to Ginsberg’s stream of consciousness, and so on. Politically, what the Beats stood for really resonated strongly with me. The Buddhist connection did as well. Kerouac’s On the Road connected with me when I was young and, later on, Bukowski really connected with me. What fascinates me about John and what his generation did—along with Chet Helms and other pioneers—they created their own counter-culture with collectives that would come together and would put on happenings and create a scene…

Working with artists like John is a good way of introducing people to what you can potentially do with your creativity as a group. Whether you’re a musician or a manager or an activist or a poet, you can work with groups of other people and create very powerful cultural happenings. He did that incredibly well and is still doing it. It’s very hard to find people people doing that today. Obviously, in certain creative enterprise zones, that approach works very well. They’re trying to do that with Detroit again now, to regenerate the city with low rents, encouraging artists to move and operate from there and work together. I think it’s a solution that everyone knows works. It’s worked really well in Berlin and East London, and it should work in all cities, really. When you get that synergy of social politics, creativity, different disciplines of art all coming together, exciting things happen. Politically, the world’s in such a mess, it’s motivating for people to want to get involved and make their own cultural contribution that isn’t just state-authorized.

There are a lot of passages on the record where John is talking about America. When you were growing up, what did you imagine America was like compared to the picture that John paints?

Youth: Well actually, the pictures that John paints with his words are very much like what I’ve imagined the scenes were like in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Interestingly, when I was growing up, I wasn’t really into jazz. I was into disco and funk and soul, but in the last 15 to 20 years, I’ve been building an appreciation for jazz. Now I love it. I’ve got a big jazz vinyl collection. So it’s been a great buzz for me is hearing John talk about people like [John] Coltrane—

—and Monk, of course, with the track ‘Brilliant Corners’ [named after the classic Thelonious Monk album/tune of the same name —ed.], where you shaped an arc, almost like a story arc, to what John was saying.

Youth: It was almost like doing a movie soundtrack with some of his stories, like ‘Let’s imagine the setting.’ I mean, on some of the other ones, we juxtaposed them with other styles of music. Poetry, spoken word can be a bit exhausting over a long period of time, so we tried to arrange it so they’re like song arrangements. We have people doing backing vocals for choruses and then John’s stream of consciousness on the verses. It gives you a little bit of a breath to take in what he’s saying. But that was challenging. It wasn’t easy getting the fit right with that.

It’s interesting that you said spoken word poetry can be exhausting. The stereotypical Beat style is a kind of aggressive, uniform, staccato way of speaking, but John’s speaking in a really calm tone, and even still I could see it getting people worked up if it were just his voice on its own. But the music you assembled around it is very reflective and inviting. It’s very bright at times. It’s like you focused on the side of him that’s really amiable, like this grandfatherly guy telling stories.

Youth: Thanks for saying that. Yeah, I mean, any one monologue eventually wears you down. It was important to somehow present it in a way that was entertaining and didn’t require complete attention all the time, where you could just groove on the vibes. Though if you do pay attention a hundred percent, it doesn’t let you down. But it’s more of a song format than a spoken performance piece. I mean, he does do his action poetries, and the whole Beat thing has always been about doing poetry live with jazz musicians in clubs, and I love that, but what we’re doing here is a bit different. Today, the spoken scene in London is quite edgy now and it blurs very much into the rap side of things. You look at artists like Kate Tempest, for example, it’s interesting how that style has been absorbed by the hip-hop scene. That’s become pop music. That’s one way of doing it, but John isn’t from a new-school of spoken word artists where he’s going to start rapping [laughs]. I just wanted him to talk in a conversational way—sometimes not even to a beat. Sometimes on the chorus, he’ll come back to the key point of what he’s saying and repeat that, and that becomes a hypnotic hook. But on some of the tracks, I got him to speak without the music, so it wasn’t to a rhythm at all.

Vinyl LP

You’re also a painter. On this recording, there are suggestions of that in the way you arrange sounds, even to someone who doesn’t already know that.

Youth: That’s great! I mean, yeah, I do a lot of drawing, painting, photography, writing, and music. There’s a certain amount of synesthesia I get. When I’m painting, I hear music, and when I’m making music I see paintings. Sometimes they all crowd-in together. A lot of the time, I try and keep them separate. They all inform each other. At the end of the day, it’s all some kind of poetry of sorts.

—Saby Reyes-Kulkarni