On his fourth album, and first since 2012’s Architecture of Loss, Valgeir Sigurðsson found himself pulled in many different directions. The Icelandic composer has long had a foot in two worlds, working in classical music while also producing songs for Feist, CocoRosie, and Björk. He’s got a full professional studio mere steps away from home, and he’s also a father of three. Sigurðsson will be the first to admit he can’t be everything to everyone—but sometimes it feels like he’s being asked to try.

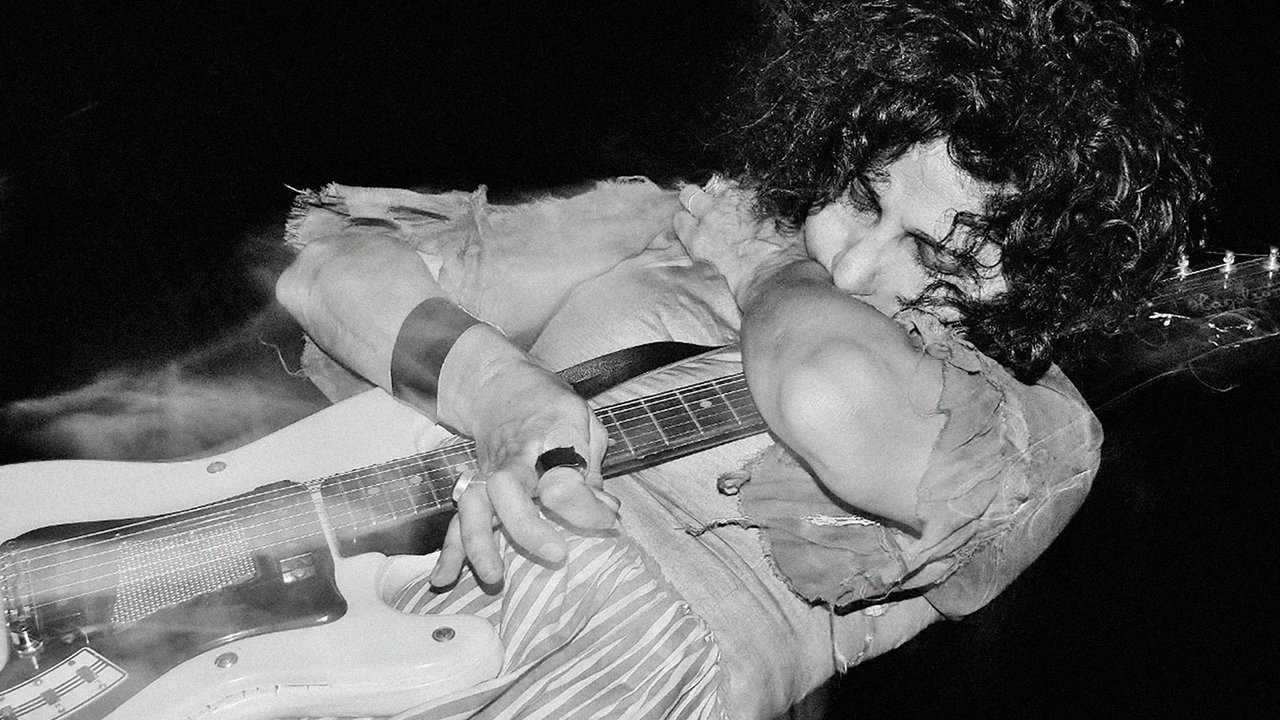

That push and pull informs the melodic—and often dark—Dissonance. To gain control over every element of the album’s eight compositions, Sigurðsson recorded string players in small groups before layering the audio to create a full orchestra. The resulting sound is both lush and surreal, with Sigurðsson likening the result to walking around a concert hall during a performance—zooming in on whatever sound catches your ear. We talked with the producer about the strange history of dissonance in classical music, the unique advantage to being Icelandic, and why the genre term “indie classical” only tells half the story.

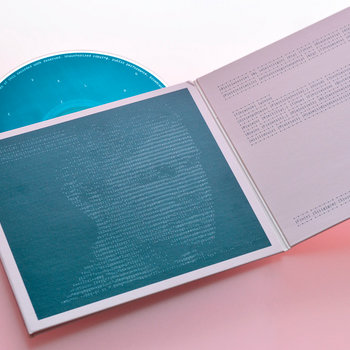

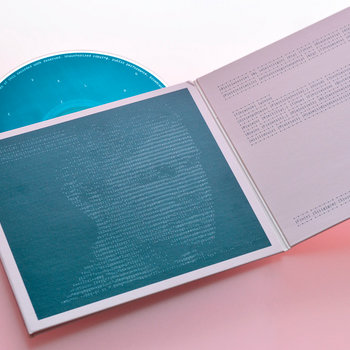

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

You’re about to release your first solo album since 2012. What has your life been like in the last five years?

It’s been a long journey with this record. I’ve written a lot of music. But a lot of it has been for performance or specific projects. It was 2015 when I started seeing this material that I had as a record. Because two of the songs are written for orchestras and electronics, I didn’t necessarily know at the time if they belonged to a solo album, or if they were out there on their own for other people to play. But they started to feel very personal. I also had twins in that period. I took a little bit of time off to structure my life around that and spend time with them.

That’s an important part of adulthood—realizing you don’t have to work yourself to death.

Exactly. When they were born, I took three or four months right after where I cleared the table completely and said ‘no’ to everything. I wasn’t going to do any projects that required the attention that some of my projects have in the past. I would only focus on what was important to me. When I started getting back into working on music, I said I’m only going to work on my own music. I started doing shorter sessions, three or four hours a day, getting people in to record sections of the pieces and gradually built it up. I kept saying ‘no’ to everything else, and not taking on new projects. I do a lot of work as a producer and on other people’s projects. There was a point when I said ‘I’m dealing with two babies—I don’t need more babies in my work.’

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

How did the combination of recording orchestrally and electronically change the recording process?

I’ve been developing this method of recording orchestra music by breaking it up into smaller sections. That’s a very time-consuming process, because I get maybe five or six string players in at a time and I focus on those parts. Then I layer. The whole string section is 40 people, but it’s all built up in a multi-track approach. Like it was rock music or pop music. That’s unusual for classical music and orchestra music. It’s a very tedious and time-consuming process. But it’s a super recording when you get there, because you get a lot of control. You can really zoom in on details. If you record an orchestra of everyone playing at the same time, there’s no way you can pay attention to everything that everyone is doing. But it means that you do everything a million times, and then see if it works together. Sometimes you have to do multiple takes and select the ones that go together in post-production. It takes time. But it was a good process for this, because I could spend a few hours a day and have my collaborators keep working on it. Then I come in with fresh ears and make notes and comments.

Did working this way help challenge you or freshen the process? Or was it driven by necessity?

I like doing electronic manipulations on acoustic sounds. I like to apply that to one little section of the recording. If I have everything recorded at the same time, I have to apply it to the entire thing. It’s like layers in Photoshop—you can distort one layer and put it back into the image. There’s something you can’t work out how that occurred in the frame. Something new happens. When I go to a concert of any orchestral music, I often wish I could fly around the room and listen in on the tiniest detail of something. Or move out and hear a blend in the room. Being fixed in one seat in the entire concert is usually a frustrating experience for me. Things like that happen in experimental music—no two people have the same experience. With electronics and the orchestra, you can do this. You do things that are a new layer to the traditional acoustic experience. You can alter the experience of the listener; I can become a little fly that travels around the room and listens to different things in different places.

How would you describe the musical term “dissonance” for the lay person?

Dissonance is something that traditionally, back in the day of harmony and beautifully-structured music, was something that was uncomfortable. You can hear it, even as a non-musical person. You hear a dissonant chord. Something sounds slightly wrong. It’s even been called ‘the devil’s chord.’ It was forbidden in music for a period of the time. We’ve gotten much more used to dissonance than listeners 100 years ago. The title piece of my album is a reimagined 45 seconds of a Mozart string quartet opening. It’s expanded and stretched out to be 23 minutes long. I got really excited about the opening of this Mozart piece. It changes into a very typical Mozart string quartet after the quick opening. So I decided to take this piece and pull it apart, stretch it out, and make it a really long song. What happens when I do that, all the dissonant chords, they gradually build up and get way more exaggerated. They’re drawn out. And then they resolve to very beautiful sunshine harmony.

I think it describes the music but also a lot of things I have been going through in my own personal life, including finding new harmony in being a father to two small babies. And also where I’m at in my professional life. There was a dissonance I had to resolve. As a human being, you go through many different kinds of things. It’s been a very extreme past four years of my life—in every way, actually. I thought that the title was perfect, to wrap up this period and to move forward.

, Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

You make a good point—even if you’re not a pop musician dealing with lyrics and hooks, you don’t write in a bubble.

I like my art to be a part of my life and my life to be a part of my art. It’s one thing. I don’t go to work and then sign out of work. I think that’s very typical for people who make art. You’re always in it in some way, even though you’re not sitting in front of your canvas or computer. But you’re always working on it in your head. There’s always things in a different stage of fermenting and getting ready for release and consumption. It’s a part of who you are. Which is why I built my studio and home in the same place. It’s a big balancing act, to combine these things and have them complement each other—not pull away from each other. It’s tricky. You open one door and close another.

It feels like in the past few years the music scene has become a little more inclusive, to the point where we don’t have to shackle instrumental music to the ‘indie classical’ label. Have you noticed the shift with your work with your label Bedroom Community?

For me, it’s a very natural thing that they exist next to each other. The way I listen to music and the way the people I work with listen to music, that’s just how it is. I think when we started the label 10 years ago, people were starting to listen to music differently, partly because of shuffling their music on iTunes—making playlists and having access to your entire music library, and then shuffling it and suddenly your computer plays Aphex Twin next to John Cage next to Missy Elliot. It’s what I naturally do as a listener. As a producer I thought, ‘I enjoy working with people. I can apply my taste and my skill in production to different types of music if I get along with the people making it.’ That’s how Bedroom Community was born.

I feel like even 10 years ago, if there was a mini-Icelandic festival in the States, you’d have a hard time booking anyone other than Björk and Sigur Rós. Have you found more opportunities and interest for musicians from your country who work in different genres?

Certainly. I don’t know why. But I think listening habits have changed. The internet has helped a lot. A lot of people are traveling more and bringing their music outside of Iceland. I think we get the opportunities and people have been coming for the Iceland Airwaves festival. We’ve been broadcast more widely. I think that’s definitely the case, that people hear from Iceland and they associate it with the possibility of hearing something interesting. It’s not guaranteed, of course. But because the music that has come out is interesting, it gives us a little bit of an advantage.

—Laura Studarus