Photo by Renaud de Foville

Photo by Renaud de Foville

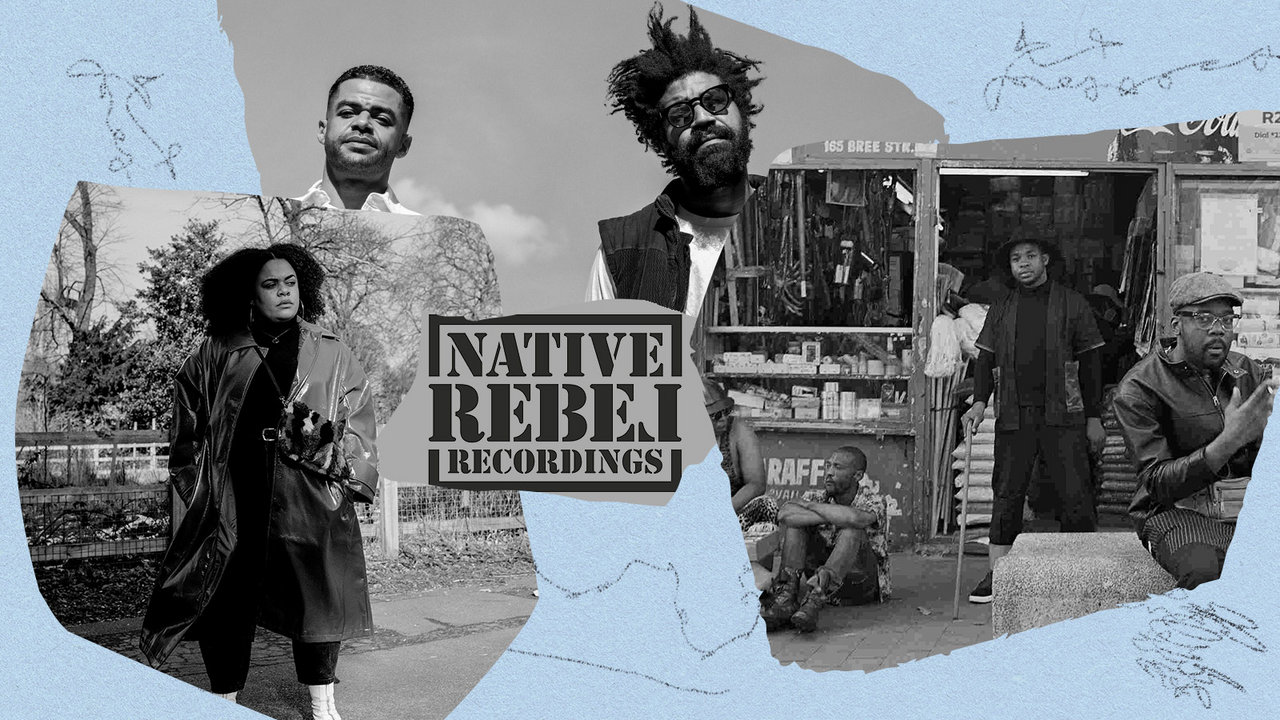

“I’m a curious guy! I like music that I don’t understand!” exclaims French artist François Cambuzat. The avant-rock guitarist is explaining the genesis of co-founding Ifriqiyya Électrique, a quintet that is currently the only Tunisian band on Western tours. Quite possibly the sole “adorcist post-industrial therapeutic” band in the world, Ifriqiyya Électrique takes their name from the area of “Ifriqiya or Ifriqiyah,” between Tripoli and Tangier, that includes today’s Tunisia.

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP,

The ensemble have become an unlikely darling of the world music circuit with their visceral, intense replication of the Banga rituals of southwestern Tunisia. They’re about to release their sophomore album via acclaimed Ljubljana, Slovenia-based label Glitterbeat Records.

The Vietnam-born Cambuzat began as a flamenco guitarist, spent time making improvised music and jazz, studied at Tunisia’s Conservatory for Oriental Music, and had a prolific career in avant-rock and punk (over 5000 concerts under his belt with bands such as L’Enfance Rouge and Putan Club). Cambuzat has always been moved by music that transports him elsewhere—“I go somewhere, I don’t care, I go into another state,” he says of his experience when he performs on stage—and the search for that trancelike state, created by the “spiritual component” in music, led him to documentary filmmaking. In 2013, he studied shamanism and music with the Uyghur community in China.

Cambuzat’s film work caught the attention of ethnomusicological circles in France. At the end of 2015, he was invited by the French Institute to study Tunisian music, where he was alerted to Banga rituals—of Islamic Sufi nature—that take place in Djerid, between the salt flats and the oases of the Tunisian southwest. This is a region where the cultures of Berbers, Muslim Arabs, and formerly enslaved Black Africans collide.

In a Banga ritual, music is played for people to dance to, inviting friendly spirits to possess them; it’s the Tunisian cousin of Gnawa, from Morocco. As with Gnawa rituals, the insistent chanting and percussion from hand drums and metal tchektcheka castanets often leads participants to fall into a trance. Cambuzat was fascinated by the rituals, as he was most interested in studying “music that has a social role.”

Ifriqiyya Électrique were never designed to be a band, but rather a temporary vehicle by which to recreate the aforementioned ritual, and to document the results of the underlying dialogue between the ancestral Banga sounds and Cambuzat’s own exploration of post-industrial noise music. Four traditional musicians—Tarek Sultan, Yahia Chouchen, Youssef Ghazala, and Ali Chouchen—play the sounds of the ritual, which are complemented by electric guitar, bass, and digital sound-shaping from Cambuzat and Italian bassist Gianna Greco, his frequent collaborator and fellow Putan Club member.

European music and art festivals, such as Denmark’s Roskilde Festival, began asking him to host performances, invitations which Cambuzat initially declined. He then consulted with the community’s Muqaddam, Hassan Chouchen, the representative who also was responsible for choosing the musicians who participated in Ifriqiyya Électrique. (“I think it will bring money, for sure, but it will also maybe bring problems,” Cambuzat remembers saying.) The Muqaddam, however, considered that the performances would be beneficial to the community, not just economically—he thought it might also shine a light on the community’s cultural assets, and, in doing so, potentially help counter racist narratives in Tunisia against Black Africans.

The current configuration of the quintet is slightly different from the original lineup. As Cambuzat comments ruefully, the money and the attention have been beneficial to the community and the ensemble’s Tunisian members, but as to the problems, “I was right as well.” Fatma Chebbi was appointed by the Muqaddam to replace Ghazala, who had been having difficulties with life as a touring musician.

Live, the band’s memorable performances are all accompanied by a video shot in the Djerid region. The visuals, culled from hundreds of hours of filming, are in sync with the music the band performs; they’re projected using a computer on which Cambuzat has synchronized the images with the beats. The resulting experience is hypnotic, exhilarating, and sometimes perturbing, and can cause fairly extreme reactions—positive and negative—in listeners.

Trying to capture a live Ifriqiyya Électrique set is a challenge, but one Cambuzat’s up for. The first album, Rûwâhîne, was designed as a long suite of different songs that are connected. For its follow-up, Laylet El Booree (which translates to “Night of Madness”), the Tunisian members of the group decided to play individual songs for single spirits, in the recreation of the annual healing gathering of the same name, where everybody is invited to get possessed.

The ideal way to listen to the albums, Cambuzat says, is to play them from beginning to end, and simply become immersed in the sounds. As he describes it, the music starts and stops when success is achieved by calling the spirit—so, as a listener, it’s best to let that process run its course, dancing and clanging along as you’re moved to do so. The art form and the ritual don’t require skill as a musician. “It’s a different way of understanding music, the very, very original way—it’s the reason people do music, to get better, to feel better,” Cambuzat says. “Music is important, but technique is for idiots! Of course you need technique, but that’s easy to have. The main thing is to know what you want to say—you need the heart.”

As to the future of the band that was never meant to be a band, Cambuzat has the “dream” that he and Greco will be able to leave behind the Ifriqiyya Électrique project, stating clearly: “It is [the community’s] music… for me, the most marvelous thing would be if they take it over.”