Papercuts begins their new album, Parallel Universe Blues, unsubtly: with ear-rattling white noise that quickly dissolves behind a single keyboard tone and water-warped guitar strums. The noise’s abrupt fade-out makes it feel like the tail-end of a scrapped track, but as the album’s first sound, it’s strangely welcoming—like walking into a house party at the height of its reverie. “Welcome to the place, lay down your briefcase,” Papercuts’ frontman Jason Quever sings on the opening track. “Pour yourself a shot, whatever we got.”

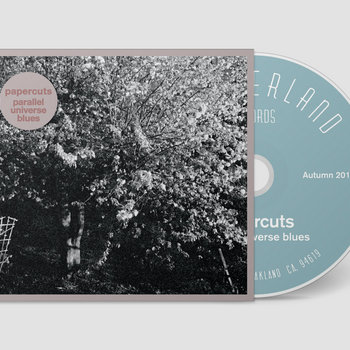

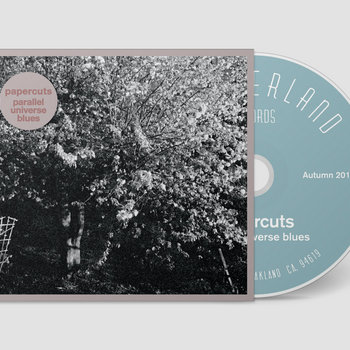

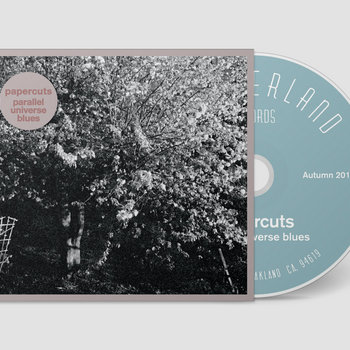

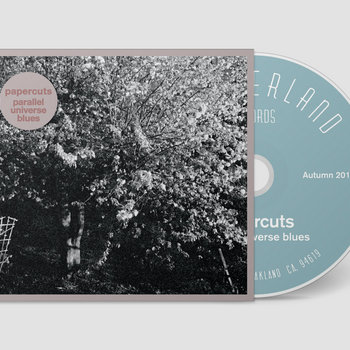

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The lines might feel flippant or haphazard if Quever didn’t time and arrange the pieces so brilliantly, if his slightly off-kilter song structure didn’t blend so perfectly with his warbling wall of sound. None of this is new: Over the course of 15 years and five albums with Papercuts, Quever has demonstrated both an intuitive mastery of warm experimental production and a songwriting voice that feels at once confessional and mysterious.

Parallel Universe Blues may not be as sonically ambitious as Papercuts’ heavily orchestrated last outing, Life Among the Savages, but it’s still an expansive-sounding and near perfect pop record that’s built on charmingly cryptic short-story lyricism and tight song construction. The hooks are plentiful and often unexpected: A soaring vocal line pulls “Laughing Man” from psych-rock molasses into something transcendent; on “All Along St. Mary’s” there’s a sharp melodic knife-twist at the end of the chorus that sends the song’s sense of longing home.

The record’s emotional centerpiece, “Clean Living,” is a cello-and-guitar-fueled dirge that recalls Nico’s slow jams with The Velvet Underground—or maybe the more somber moments of Siamese Dream. On a record thick with production tricks, “Clean Living” is built around a single drum and a minimal instrumentation, advancing a story of attempted sobriety that is both funny and aching. Getting clean is a recurring theme on an album that deals with uncertain states of consciousness, sleep deprivation, order, and chaos.

Despite fleeting sonic resemblances to L.A.’s ‘60s Paisley Underground or ’80s radio deep cuts, Parallel Universe Blues retains something hauntingly personal—and it’s just a little bit frayed around the edges. That’s intentional.

“I try to make it not perfect, you know?” Quever says from his studio in Los Angeles, where he moved two years ago from his longtime home of San Francisco. “But I try to make it hopeful and positive during the process. It’s like photography: You can pose for a photograph, but how you look that day is just how it is—there’s nothing you can do about it. How you feel when you’re recording comes through no matter what you do. So I think you have to try and trust yourself.”

Perhaps taken aback by his own confidence, he quickly adds, “Music is the only thing in my life I look at like that.”

Quever’s openness when he speaks is rare and disarming, but it’s leavened by what seems like a terrorizing self-awareness. He abandons sentences when they run the risk of seeming self-indulgent with a quick “I dunno”; he’s often said that he’s not entirely comfortable being the center of attention. Which feels a little strange considering he is Papercuts—though the band has had many members over the years. Quever was raised in a Northern California commune until he was 10, and lost both of his parents by 20. He calls his childhood “chaotic, for a lot of reasons.” And while it would be easy to use that information to build a narrative of Quever as a tortured artist, in truth, he says, he’s not sure how death and instability have affected his life.

“You can’t really take anything for granted,” he says. “That’s been slammed into my face over and over again… This can all go away at any time. But I try to put a positive spin on that. When I first started [releasing albums], it was striking the way the music was exciting to me, but it came off as sad to other people.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

There is definite sadness in Papercuts’ first LP, Mockingbird—you can hear it on the piano-driven “A Fairy Tale,” a song about ridding oneself of illusions of control—but there’s also a clear blueprint for the majestic records to come: wobbling spiral structures reinforced with walls of woozy, layered organ, reverb-drenched vocals, and inventive hooks that pull it all together. Tender songwriting and lush production are two disparate disciplines, but they’ve always been inseparable for Quever, something he traces back to listening to the Beatles as a kid. “I think I heard the fast version of ‘Revolution,’ and even early—when I was 10 or something—I thought, ‘Why is the snare tone like that?’” he remembers.

When he’s not making music as Papercuts, Quever is often recording with other artists. He’s worked (and toured) with Beach House, and made albums with Cass McCombs and Casiotone for the Painfully Alone. “I really like working with bands,” he says. “I get to help other people, and that feels very therapeutic—having good relationships with people.”

Despite the fact that each new Papercuts album has been better than the one before it, Quever’s music hasn’t found a huge commercial audience. His last three albums have been released on three different labels, and while his audience has expanded, Papercuts remains a critical darling without a breakout success. Quever points out that he’s “never been a road dog,” and it’s hard to grow a large audience without constant touring or a tight album release schedule. But he’s also not particularly interested in thinking about Papercuts as a commercial endeavor.

“When you’re starting out, you think you’re not successful if you’re not famous,” he says. “And you have to burst that bubble. It’s not just that it doesn’t mean anything to me, it’s that I know it doesn’t mean anything to the people who get it. I love the idea that if I go and make another record, maybe more people will want to hear it. That’s exciting, and I’m not pretending that it doesn’t affect me. But I had some records that got a lot of press, and I got to tour everywhere, and it didn’t bring me any happiness.”

“I have a very clear goal,” Quever says. “My goal when I made this record was to not make something commercial—I just wanted it to sound like a band that was having a good time and pushing themselves. I wanted it to be messy. There’s a niche thing there that I hope will find its way and survive. And I projected that enough people might like it that I could go to the next lilypad.”