Photo Courtesy of the Center for Contemporary Music Archive. From left to right - Bill Maginnis, Tony Martin, Ramon Sender, Mort Subotnick, and Pauline Oliveros.

Photo Courtesy of the Center for Contemporary Music Archive. From left to right - Bill Maginnis, Tony Martin, Ramon Sender, Mort Subotnick, and Pauline Oliveros.

The San Francisco Tape Music Center was created under the premise of utilizing magnetic tape and electronics as compositional tools, but its legacy has touched nearly all aspects of the avant-garde. The Center’s foundations were laid by a handful of progressive West Coast composers and artists who were interested in electronic music, the tape medium, and the idea of pushing art forward.

The story begins in the early ‘60s, when radical ideas and reactions to the fear-based Cold War ideology of the ‘50s began to take hold. In 1961, Ramon Sender, a student of composition at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music under Robert Erickson, started using magnetic tape in his work—the school had a two-channel Ampex tape recorder. That simple piece of gear allowed Sender to record sound on top of sound, resulting in his 1961 composition Four Sanskrit Hymns. Sender created an electronic music studio in the conservatory’s attic where he recorded compositions like KORE and KRONOS, both of which utilized electroacoustic sourcing. On KRONOS, for instance, Sender uses a pair of scissors on a large sheet of metal, improvisations from choral students, a piano soundboard, and an oscillator to create an unsettling, though moving, work of musique concrete.

Soon after, Sender and composing colleague Pauline Oliveros collaborated on a series of concerts called Sonics. The first Sonics concert took place on December 18, 1961 and featured music from Ramon Sender, Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, and Philip Winsor. Oliveros’s Time Perspectives, Sender’s Traversals, and Riley’s M…Mix (also known as Mescalin Mix) were all tape-based compositions: Sender modified accordion sounds while splicing in sounds of his son bouncing in a crib. Oliveros hand-wound a tape recorder while in its recording mode, making the frequencies modulate with the varying speed. Mescalin Mix was a piece that originally used a 35-foot tape spool snaking through wine bottles that acted as spindles. The Sonics series garnered positive reviews in magazines like the San Francisco Chronicle, but the Conservatory decided not to renew their involvement.

In the summer of 1962, Sender invited composer and teacher Morton Subotnick to start a new programming and production organization, which they would call The San Francisco Tape Music Center. It was at the Center that Subotnick created works like Mandolin (1963) and Play! No. 1 (1964). The two composers pooled their equipment together and moved it—along with three Hewlett Packard wave generators from the Conservatory—to a Victorian mansion at 1537 Jones Street in San Francisco. This move also meant that the Tape Music Center was entirely independent, and could partner with organizations like the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Actor’s Workshop, and more, which led to more radical, collaborative events—often referred to as “happenings”—such as 1963’s City Scale, a performative piece involving much of the city’s avant-garde. This happening took place over six hours throughout San Francisco, aiming to “blur the boundaries between art and life.”

In a bittersweet turn of events, in the spring of 1963 Sender accidentally set fire to the roof of the building at 1537 Jones Street, due to an issue with a faulty fuse. Luckily, he and Subotnick had already found a more suitable space: 321 Divisadero Street, the address with which the Tape Music Center is most frequently associated. This building had two auditoriums, which were sublet to the Anna Halprin Dancers’ Workshop and radio station KPFA. The electronic studio was on the third floor.

At Divisadero, the Tape Music Center’s core members grew to include Oliveros, Tony Martin, and William Maginnis, as well as Michael Callahan, whom Sender called a “teenage electronic wunderkind.” In David Bernstein’s book The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, the author notes Martin was a visual composer working with “hand-painted slides, liquid projections, film footage, and other techniques” during performances and art happenings. Maginnis was a studio technician who took care of much of the Tape Music Center’s hardware.

Compact Disc (CD)

During this period, Subotnick and Sender enlisted the help of an engineer named Don Buchla to streamline electronic music composition by making tape splicing unnecessary. This resulted in a machine that Buchla delivered in late 1965 called The Modular Electronic Music System, but was colloquially called The Buchla Box. The synthesizer still works, after undergoing heavy maintenance in early 2010 by Rick Smith, an apprentice of Buchla’s in the early 2000s who has restored many Buchla modules and systems, and owns the largest, most complete collection of Buchla instruments.

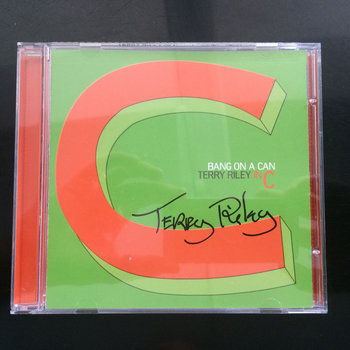

At Divisadero, much of the Tape Music Center’s focus continued to be spent on live events. Performers like theorist and electronic musician Milton Babbitt, minimalist luminary Steve Reich, synthesist and academic James Tenney, electroacoustic pioneer Luc Ferrari, and many more performed groundbreaking compositions. At a concert on November 4, 1964, Terry Riley would debut In C, a landmark in minimalist composition that continues to be played by ensembles such as Brooklyn Raga Massive and Bang on a Can. Steve Reich would perform It’s Gonna Rain and Livelihood at the Tape Music Center on January 27, 1965.

The Tape Music Center ended in 1966 after securing a $200,000 grant from the Rockefeller foundation, provided that they associate with an academic organization. The Center connected with Mills College, where it was called the Mills Tape Music Center, before becoming The Center for Contemporary Music. Oliveros stayed on for a year as the center’s first director. But Subotnick and Sender moved away—Subotnick going to New York with Actor’s Theater, which became the Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, and Sender joining the Morning Star Ranch. The core group would go on to be visionaries—Subotnick released the deeply influential Silver Apples of the Moon in 1967 and continues to make music, lecture, and perform; Oliveros created the Deep Listening Institute, wrote many books, and taught music all across the United States. But the impact they made at the Tape Music Center in the early ‘60s can still be felt, and much of its archival material—including the original Buchla Box—can still be found at Mills College.

The author would like to thank the staff at Mills College’s Center for Contemporary Music for their assistance in this article, including Maggi Payne who toured the author through the center, Ramon Sender who assisted with fact-checks, and David Bernstein who wrote the book .