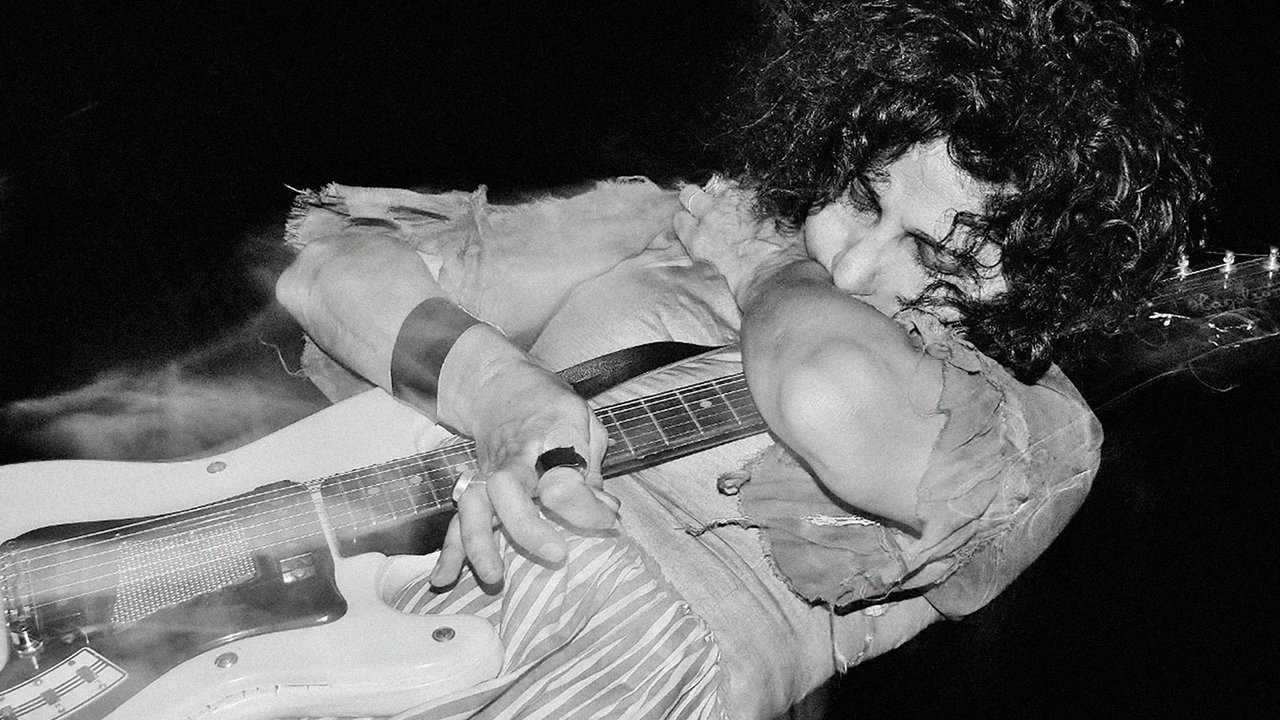

Photos by Ash Kingston

Photos by Ash Kingston

When serpentwithfeet sings on his debut album, soil, he doesn’t just use one voice—there is a whole city of them. There is the voice that populated his breakout blisters EP—a high, searching croon trained on years of church choirs. But there are also growls and wails, voices he says that sound like they could come from scared little boys and washed-up opera singers, voices tagged in the record’s dense mix as “howling peacock.”

They thunder into earshot in unison during the first seconds of “cherubim,” a startling track about the serious, holy duty of loving a romantic partner. “Sowing love into you is my job,” he declares longingly while a monster grunts percussively in the background. “Anything else is a weak curse.”

Over the past four years, serpentwithfeet has served as the recording moniker for the artist born Josiah Wise, who answers the phone as “serpent.” In 2016, he signed to the boutique electronic label Tri-Angle, and worked with the British dark ambient producer Haxan Cloak on the five lovelorn songs that would become blisters. While much of his vocal style—its versatility, its gravitas, its high, silky runs—takes influence from R&B greats like Brandy, serpent’s music lives closer to the fantastical universe of Björk, an idol of his who became a mentor and collaborator when she asked him to remix her song “Blissing Me.” Both artists have a holistic creative practice that incorporates lavish music videos and intense live performances. Both thrive in the space where the organic meets the technological, where the human voice ricochets against machine-made beats.

It’s one of the first warm days of the year in New York when we speak, and serpent is running errands. Sirens and car horns blare across the line. The overwhelming simultaneity of the biggest city in America seems to suit serpent, who moved to Brooklyn after a stint in Philadelphia (he’s originally from Baltimore).

In his music and in his life, he is interested in the messy, self-contradictory whole of the human psyche, the enormous paradoxes swarming beneath the skin. Recently, in an effort to explore himself more deeply, serpent went back to his origins. “I talked a lot with my mother in the past two years,” he says. “I called her crying a lot, and she always had great advice. It was the most amazing thing I could have done. It really gave me a lot of grounding, which is why I called the album soil.” He got, he says, his “isms” from his mother—his dramatic flair, his sensitivity—and speaking to her about her relationship with his father helped serpent better comprehend his own romantic exploits.

While blisters focused on the end of a dysfunctional relationship, soil takes into consideration all the different facets of romantic connections. There are songs about giddy new love, like “cherubim” and the rapturous piano ballad that closes the album, “bless ur heart.” Songs like “messy” and “invoice” explore the often painful process of opening up to a new partner for the first time.

On “mourning song,” serpent traces the hole left behind at the end of a romance, and the necessary work that goes into healing it. “I want to make a pageant of my grief,” he says. He often sings of work, even in the honeymoon songs. Love, for him, never simply floats into your life perfectly formed. Love puts you to work. It takes hard, constant labor to communicate with another person—and also to excavate yourself, to come to terms with your flaws so you can learn to love better, to grow in tandem with the person you love.

The work, he says, is “the good stuff… I’m really into the muck. That’s something I’ve had to learn about my own personality. I like the intense parts. I don’t trust it when it’s all cupcakes.” He recognizes that this inclination in some ways undercuts cultural mythologies of romance, the happily-ever-afters of teen dramas and prestige movies alike. “I think perhaps it’s an American thing; you always want the color yellow, you always want pink, you always want it to be fluffy,” he says. “And I love fluffy. I love cotton candy. That’s beautiful, but so often we sweep things under the rug because we live in a world that says, ‘Get over it.'” He’s quick to add, though, that he never wants to conflate work and abuse. “I’m definitely not saying that we should make space for toxicity or violence. I’m definitely not saying that we should suppress our needs. And I definitely don’t think that we should compartmentalize ourselves. But I’ve always thought of relationships as being work, and sometimes that work is tough.”

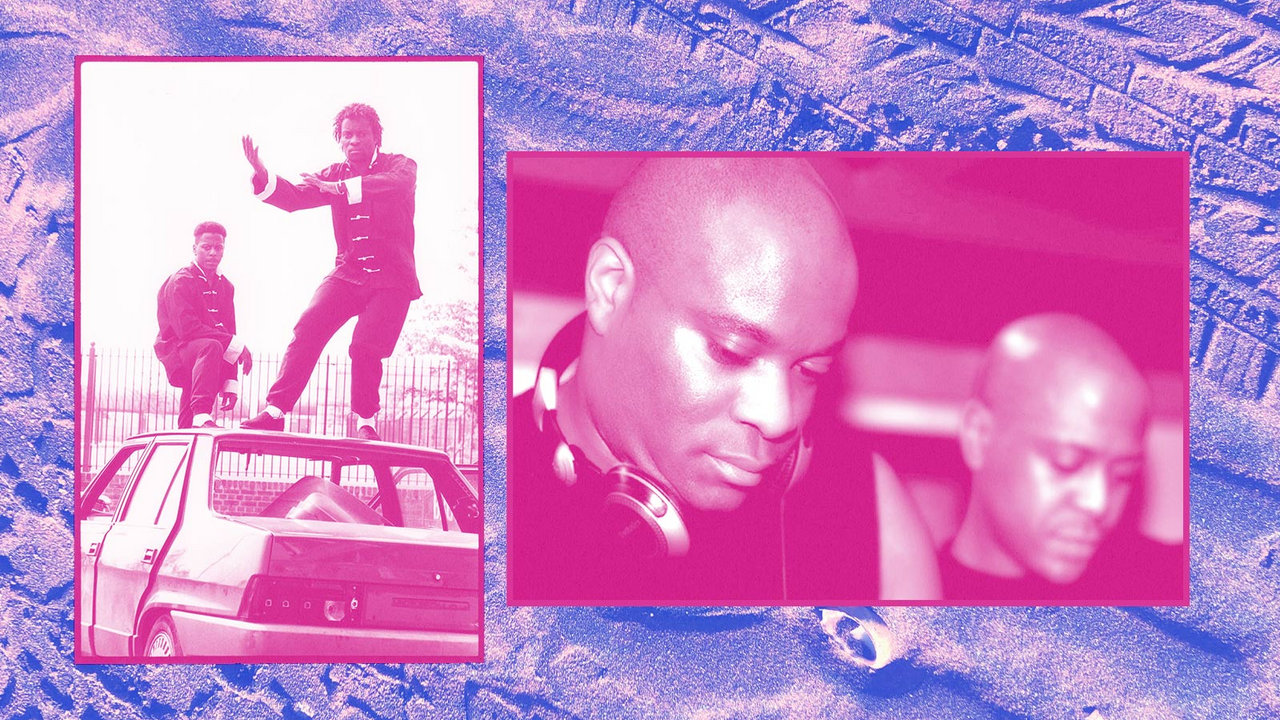

The album is an attempt to see what’s under the rug, to hold up its tangled secrets. In the two videos so far released from soil, for “bless ur heart” and “cherubim,” serpent surrounds himself with artifacts: toys (like the dolls he collects and tours with), fabrics, colored pencils. The sets are strewn with objects of play, like an imaginative child’s room.

In “bless ur heart,” serpent wanders the halls of an ornate building—it might be an opera house or a theater—playing with two glowing, hovering moons. In “cherubim,” he’s joined by another boy in a beautiful decaying house. They chase each other around like kids; they jump rope together; they sing to each other through a hole in the wall. Wanting to preserve the magic of the visuals, serpent doesn’t tell me where these videos were shot. “These songs are both very fantastical,” he says. “They’re songs of operatic proportions. I wanted them to feel grounded in the natural world, but also a little bit outside of our world, or in the world of imagination. The setting added a lot of character.” Watching the videos is a bit like looking through a porthole into a world displaced from time. It’s familiar and strange, like a deeply lodged memory.

To spread a similar uncanny effect throughout soil, serpent brought on co-producers mmph, Clams Casino, and Katie Gately. Gately’s fingerprints can be heard on six of the album’s songs; she’s the one responsible for twisting serpent’s voice into bizarre shapes on “cherubim” and “messy,” where he sings in a nasal, corroded register about growing closer to a lover via exposing his own flaws. Before he worked with her, serpent “would never let anybody touch my vocals—producers can do what they want, but don’t touch the vocals,” he says. “Except for Katie. Katie touches the vocals and I’m like, ‘Yeah, actually, your idea is better.’ She’s someone that I can completely trust sonically.”

In order to build the album’s dense choir of voices, serpent first recorded dozens of vocal tracks in the studio, then sent them to Gately to tweak. “I knew coming into this album that I wanted the vocals to be the most present. I wanted them to have the most real estate,” he says. “I recorded a lot of vocal tracks using playful voices. Some songs might have 30 vocal tracks before they go to Katie. And she would send them back and she would make them sound like monsters or ducks or babies. We just had this crazy choir of sounds. I wanted ‘cherubim’ to feel like a town hall meeting, everyone stomping and singing. I needed it to feel very communal.” He likens that choir to the cast of characters in a novel or a TV show: a story that needs dynamic personalities in order to unfold. “When you think of Sesame Street, it’s not just Maria in the neighborhood. You need the muppets and the furry things, too,” serpent says. “It can’t just be people. You need everybody to tell that story. Katie is resourceful; she’s almost like a great fiction writer.”

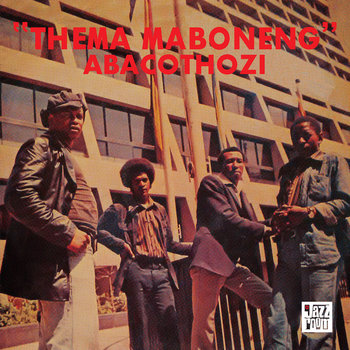

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The album ended up taking a darker tone than serpent first envisioned. After blisters, he wanted levity, to indulge the light and playful sides of himself. He imagined a record full of “heavenly harmonies” contrasted with “heavy beats.” But when he arrived at the studio after touring with Perfume Genius in 2017, all he wanted to do was growl. He found his voice had changed; he had more stamina thanks to singing every night, but he also had more darkness, more grit. “Hearing my voice differently inspired me to think about myself differently,” he says. “It inspired me to think about being a more expansive person. I don’t have to do these mellifluous vocals. I can growl, too. I can growl and I can roar. I don’t want to wear heels. I want to wear boots and I want to stomp. I want to really rumble now.”

While touring last year, serpent spent night after night with the songs on blisters, to play host to them, as he puts it, to invite them onto the stage. He has a magnetic performance style—instead of bantering between songs, he sings his observations about the room, the crowd, the evening, riffing fluidly between verses. He has a way of making a song he’s performed dozens of times feel immediate, as though it’s just occurring to him. As he reanimated these songs about heartbreak over and over, he began to realize that he was so much more than his sadness.

“I’m not this austere, brooding person who wants to sing about how some guy didn’t satisfy me,” he says. “That is a part of me. I do think it’s important to complain, and that’s something I’ve learned to do with more gravitas in the past few years—to say, ‘I’m not happy and my unhappiness has merit.’ But now I also want to laugh and joke and roll around and bring my dolls and toys and talk to imaginary people on stage. I want to do all of it.” He brought that desire to soil‘s recording sessions, where he found himself inhabiting his multiplicities. Suddenly, being an artist didn’t mean boxing himself in to a particular sound or a particular mood. It meant expanding himself as far as he would go. “Midway through recording soil, I realized: I get to be all of my selves.”