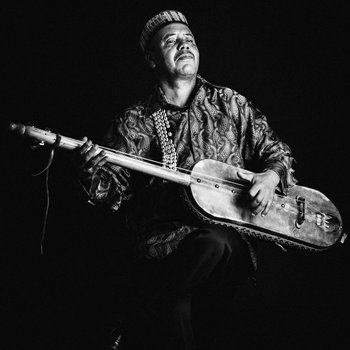

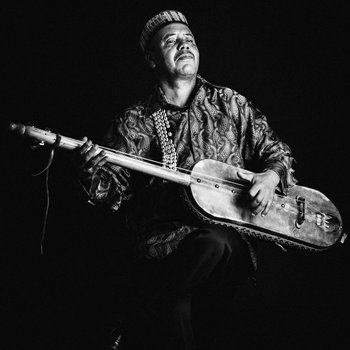

Maalem Mahmoud Gania

Maalem Mahmoud Gania

“Gnawa has always played a spiritual role in communities,” explains Moroccan musician Samir LanGus, speaking from his current home in New York City. Originally from the coastal Moroccan city of Agadir, LanGus now plays his own updated take on traditional Moroccan music in New York, as well as performing as part of Innov Gnawa with fellow North African expats. “For centuries, it was practiced only by the Gnawa community [descendants of slaves in Morocco and Algeria], but within the last 60 years or so it has opened up to the whole Moroccan community.”

The traditional form of music—currently part of Moroccan tradition, but with roots further down into Africa—gets its name from the Gnawa people, who have historically played it. Gnawa music has connections to all-night rituals called lilas, where people who are in need of physical or spiritual healing gather to witness and dance along to lengthy jams built atop hypnotic rhythms that are played out on the castanet-like krakebs. The dancing singers spin their tasseled hats in circles and insistently shake the krakebs behind a Gnawa music master, the “Mâalem” (variations on spelling include Maleem, Maalem, or Mâallem), who plucks away at a bassy guembri lute while singing lead on the ceremonial call-and-response chants.

Sonically, gnawa sits at the crossroads between a variety of music—the quivering cascade of flamenco’s castanets, the deep spiritual cry of the blues, improvised ragas, and the cyclical trance of minimal techno—and has gained increasing international recognition as a key Moroccan art form.

LanGus says the timeless heritage of Gnawa needs to be preserved for future generations. “With the actual state of things in this world today, we feel that traditional music like Gnawa is essential and vital for the health and well-being of such a rapidly changing world.”

The history of the genre is somewhat hazy, mostly passed down through oral tradition. Clues to its origins however, remain hidden in the lyrics of the repertoire. “We do know that almost the entire repertoire was once sung in Sub-Saharan dialects,” LanGus explains, “up until around 60 years ago, when Gnawa became fully assimilated in Moroccan society.” Remnants of non-Moroccan languages—such as Bambara from Mali, or Fulani and Hausa from the Sahel region—remain scattered throughout the Gnawa repertoire, alongside a majority of words now sung in Moroccan dialects.

Some of the renewed recent interest in the Gnawa began after the death of one of the genre’s key international figures, Mâalem Mahmoud Ghania, in 2015 (his name is often spelled Guinia and Gania, as well). Ghania met or recorded with various well-known Western musicians in his lifetime—among them Bill Laswell, Pharoah Sanders, Carlos Santana, Peter Brötzmann, James Holden, Floating Points, and, as legend would have it, Jimi Hendrix—and is considered one of the genre’s best known proponents. His sons, particularly Mâalem Houssam Ghania, are following in their father’s footsteps; Houssam tours widely and is due to play with British producer James Holden at festivals this year.

“I grew up in this art since my birth,” says Houssam. “Gnawa music is more important than ever, because it has become a universal music.”

Gnawa is deeply rooted in tradition. Becoming a Mâalem not only requires being able to play for hours straight, it also requires a surgical knowledge of the repertoire. This includes knowing song orders (which vary from city to city), which incense to use, and the ability to play every instrument in the ensemble. As LanGus puts it, “You need to dedicate your entire life to becoming a Mâalem.”

Despite its deep traditions, modern Gnawa is evolving. Firstly, a growing number of international collaborations have melded the genre with Afrobeat, techno, jazz, and more. Elsewhere, recent highly-regarded releases Magnetoception and Simultonality by American composer Joshua Abrams put Gnawa’s lead instrument, the guembri, at the heart of his albums.

The emergence of female Gnawa masters is also a welcome milestone. Hailing from Casablanca, 20-year-old Asmâa Hamzaoui and her group Bnat Timbouktou are the first all-female group to play Gnawa. Born into a Gnawa family, Hamzaoui’s father was a Maâlem, and her mother organized local lilas.

“At the age of seven I touched the guembri for the first time,” remembers Hamzaoui. “Sometimes, my father even let me play a little. When he noticed my interest, he made me a little guembri. Later, my mother had an accident and became paralyzed from the legs down, so I decided to start really learning the Gnawa tradition—to help my father and all the family.”

As Hamzaoui explains, the role of women has always been vital to the Gnawa tradition: organizing lilas, singing along, clapping, and dancing. Few, however, have ever been known to play the music—officially, at least. Like any other Maâlem, Hamzaoui had to go through the process of learning every aspect of Gnawa; two years ago, she finally formed her group, Bnat Timbouktou.

“You know, I’m only 20,” she says. “You can imagine the pressure you have from Gnawa men and critics; people who says that this music is only for men… So I’m really proud playing it. It’s a national patrimony, and an African heritage known to heal souls. I think I heal myself when I play. When I have a foreign audience who don’t understand my language closing their eyes and dancing to my music, I think I’m healing them in some way, too.”

With Gnawa’s increasing recognition and development in mind, this list provides an introduction to both the staunchly traditional and more progressive sides of the Gnawa genrem via a handful of albums present today on Bandcamp.

Traditional Gnawa

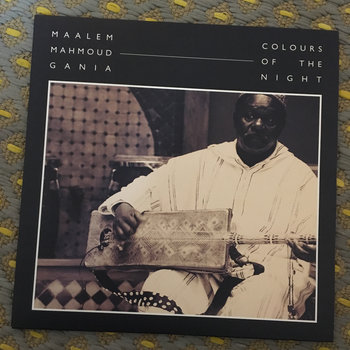

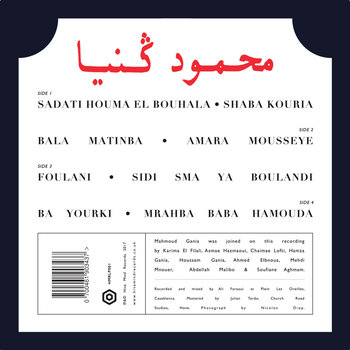

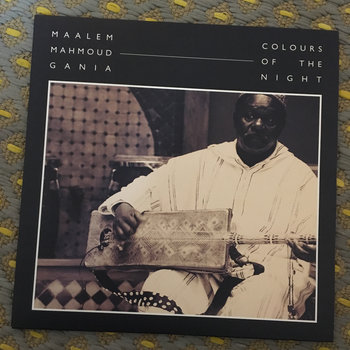

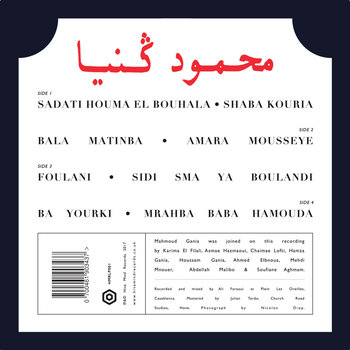

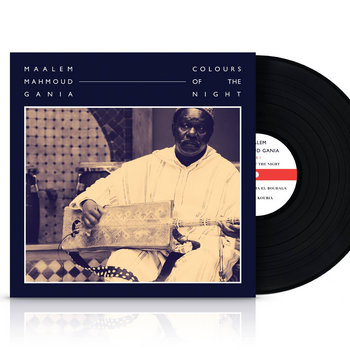

Maalem Mahmoud Gania

Colours of the Night

2 x Vinyl LP

This LP release of recordings by the late Maâlem Mahmoud Ghania is as good an introduction to the genre as you’re ever going to get. The music’s sheer hypnotic power has never been captured on tape quite this unadulterated outside of a six-hour lila somewhere in rural Morocco. These sessions actually represent the last recordings made by Ghania before his passing in 2015.

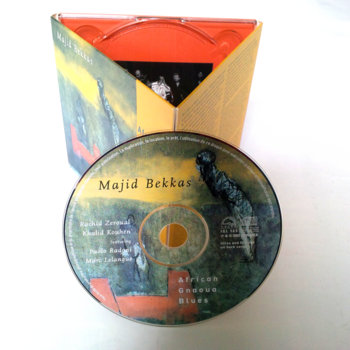

Majid Bekkas

African Gnaoua Blues

Compact Disc (CD)

A key album in the genre from the early ‘00s, this album by Majid Bekkas (originally from Salé in Northern Morocco) does a good job of demystifying the connections between Gnawa and American blues and jazz traditions. Bekkas’s guembri playing and the hypnotically persistent shaker rhythms of percussionist Khalid Kouhen stick to the strict DNA of the traditional Gnawa sound, but flute and kaval solos by Rachid Zeroual, plus Bekkas’s own overdubbed slide guitar and oud crack it open with new jazz and blues inflections. This also spawned a killer remix EP released last year by Manchester label Banana Hill (see Cervo Edits below).

Innov Gnawa

Innov Gnawa

Vinyl LP, , Compact Disc (CD)

Formed by Moroccan expats in New York City, this group stick very staunchly to the ancient ritual of Gnawa music. For example, the six songs on this debut recording were culled from an eight-hour performance recorded in a Brooklyn warehouse. Fronting the group is Maâlem Hassan Ben Jaâfer (another brilliant album of his is mentioned below, too). Even by the standards of Gnawa this one’s an intensely ecstatic and hypnotic recording. The group also notably collaborated with British producer Bonobo, on a track on his 2017 album, Migration.

Hassan Ben Jaafar, Itamar Ziegler and Balkan Beat Box

Nas Al Hal / Hassan Ben Jaafar & Friends

This album, featuring Innov Gnawa’s frontman, came together over relatively spontaneous sessions after he was invited to collaborate with Israel/New York trio Balkan Beat Box. It’s an unusually soulful set of Gnawa tunes. The music is far more laid-back than normal, and often veers into a funkier rhythms and inflections more closely associated with Malian desert blues. Exploring the music’s multi-faceted heritage from both above and below the Sahara this is one of the most user-friendly (and varied) of Gnawa albums.

Remixes & International Fusion

Simo Lagnawi

Moroccan Fusion

Released online in 2017 by Best Foot Music, a non-profit UK organization aimed at “promoting and documenting musicians who have moved to the UK from around the World,” Moroccan Fusion is a record lead by Simo Lagnawi, a Gnawa musician living in the UK. He’s also played in collaborative projects with British fusion bands such as Electric Jalaba. This recording however, more closely resembles traditional Gnawa—albeit with some additional instrumentation and an intensely loose feel. Most importantly, that key element of “spiritual trance” remains solidly intact.

Majid Bekkas

Soundani Manayou / Mrhaba (Cervo Edits)

Vinyl LP

These club-ready edits of two Majid Bekkas tracks from the 2002 album mentioned above are quite miraculous. It’s incredible how a tiny handful of additional drum beats turn Gnawa into something so closely resembling minimal techno.

Maâlem Mokhtar Gania & Bill Laswell

Tagnawwit – Holy Black Gnawa Trance

Bill Laswell has long been a fan and supporter of Gnawa music internationally, organizing and producing the meet-up between Maâlem Mahmoud Ghania and Pharoah Sanders in 1994. This album from 2016 has Laswell hook up with the late Mahmoud Ghania’s brother, Maâlem Mokhtar Ghania, for an album of fusion featuring a cast of notable session musicians (including Chad Smith from the Red Hot Chili Peppers).

Laswell essentially interleaves new tracks of horns, guitars, keyboards, plus his usual atmospheric treatments into initial sessions with Mokhtar Ghania. It’s a thoroughly entertaining spin on the genre, particularly the final track “Mabodallah Allah Dayyim” getting thoroughly weird in its second half as Fourth World cornet sounds enter the fray and a Western drum kit tangles the Gnawa rhythms into new psychedelic shapes.

Maleem Mahmoud Ghania with Pharoah Sanders

The Trance Of Seven Colors

Laswell also connected Pharoah Sanders with Mahmoud Ghania in 1994 for this jam recorded in Essaouira, Morocco. It’s a pure mix of Sanders’s sax with Ghania and his band, reaching some glorious and unrepeatable heights. “Moussa Berkiyo/Koubaliy Beriah La’ Foh” is a highlight, built atop some extra hard handclap rhythms. Sanders seems almost out of his depth on the track, lost in the trance of the ritual, barely able to play. It’s utterly out of character from the man’s signature godlike rasp. Perhaps the rawest fusion of American Jazz and North African traditions ever recorded.

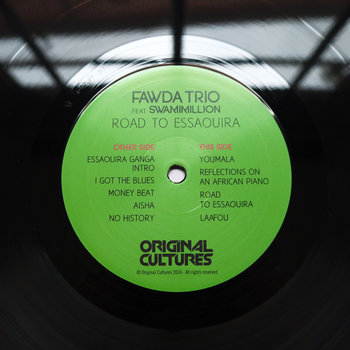

Fawda Trio ft. SwamiMillion

Road To Essaouira

Vinyl LP

Recorded in Essaouira in 2014, this album documents a trip by Bologna’s Fawda Trio to discover Gnawa traditions. In addition to the contributions of London’s SwamiMillion (two members of LV, a production unit associated with the Hyperdub, Brownswood, and Soul Jazz Recordings), a host of Moroccan guests are featured on the recordings, including Maâlem Allal Soudani, descended from a long line of Gnawa musicians. It’s a blast of a record, full of heaps of color.

Fanga & Maalem Abdallah Guinea

Fangnawa Experience

Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

Featuring another brother of Mahmoud Ghania, French Afrobeat outfit Fanga met up with Maâlem Abdallah Guinéa for this album recorded live in 2011. It’s a seamless blend of Afrobeat funk and Gnawa ritual, somehow managing to neither lose any of that inherent joy in Afrobeat, nor the ritual trance states of Gnawa. It’s tragic that Maâlem Abdallah Guinéa passed away in 2013 before the project could record again.