Morgan Rosskopf has been working with plants for most of her life. She began at 16 and, aside from the years she spent getting her MFA in art, she’s worked with them ever since. “I love plants, because they have no ego,” she says. “They have no baggage and live a simple life. They are mostly self-sufficient. I find these qualities deeply inspiring. I want to learn these lessons from the plants as I take care of them.”

Rosskopf believes that plants have some form of consciousness. She speaks to them, and tries to always interact with them in a loving way. And when she goes to work at Fieldwork Flowers, a floral and plant operation in Portland, Oregon, she chooses the music she plays during the day with the plants in mind. Often, it’s music designed for zen meditation. Occasionally, it’s Mort Garson’s 1976 LP, Plantasia, written and recorded to be played for both humans and plants. “I really like the album a lot,” Rosskopf says. “Even though it was made with synthesizers, it still doesn’t fit into what many would consider ‘electronic.’ Once I was playing it at work and a customer mentioned that it sounded like music from Super Mario World. I loved that comparison, because in video games there’s an obvious suspension of disbelief—and sometimes people need to suspend their disbelief just to be open to new ideas.”

Garson’s Plantasia has become a cult classic among green thumbs and early electronic music fans alike. The ‘70s presented a high water mark of speculation about the ability of plants to think and feel, ignited by the 1973 book The Secret Life of Plants and a later documentary by the same name (with a sprawling, psychedelic soundtrack by Stevie Wonder). The book suggested, among other far-out ideas, that plants retained psychic and telepathic powers. However, a New York Times review at the the book’s release remained unmoved. “Unexplained phenomena lend themselves to a lot of anthropomorphizing and the naive postulation of all kinds of ‘rays’ and ‘energy fields,’” in the book, they wrote. “Which sound every bit like psychotic fantasy.”

But at least one of the central ideas from the book took hold, and has been the subject of many conflicting studies: That plants could “hear” music and vibration. And while most mainstream scientists recoil at the concept—quick to point out that plants have nothing resembling a human brain, let alone ear canal—the idea has taken hold with plant people. Marijuana growers, in particular, have been open to the concept. An informal poll of legal growers in my home state of Oregon suggested that classical and reggae music were favorite genres.

There are a handful of artists who write and record music with plants in mind. Some of them approach their compositions with particular frequencies (purported to aid in plant growth) in mind, while others just imagine what their plants might enjoy.

Brendan Wells’ Plant Music

Music for People & Their Plants Vol. 1

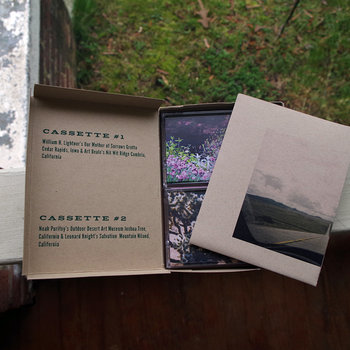

Cassette

If you imagined the sounds of photosynthesis, you might wind up with something similar to the hypnotic synthesizer compositions on Minneapolis-based musician Brendan Wells’s Music For People & Their Plants Volume 1.

Wells grew up in Des Moines, Iowa, and his first real band was a noise-core outfit called Patrick Swayze’s Ghost. He’s performed in punk and hardcore bands over the years, and currently plays bass and sings in the band Uranium Club. “It’s weird to think viola lessons, powerviolence, and The Cars got me to where I am now,” Wells says.

In 2016, Wells took a job as content coordinator at Maximum Rocknroll magazine in San Francisco, but he found it stressful and isolating. He quit after six months. “After that I couldn’t listen to punk music without feeling terrible anxiety, so I thought I’d start listening to classical music.” Wells wound up interested in 20th century minimal composers, discovering Mort Garson’s Plantasia LP, and reading The Secret Life of Plants. His Plant Music project grew from there.

For Wells, plant music has little to do with finding frequencies to aid plant growth—it’s a conceit that allows him to ignore his self-criticisms and indecisiveness. “When I’m recording this stuff on my own at home I’ll look at a plant and ask myself, ‘Is this plant music?’ and base my decisions on that. Maybe it’s more appropriate to say it’s what I would listen to if I were a plant: something simple, minimal, repetitive, calming. A plant works slowly, so I like to keep a leisurely pace, but I like to think a plant does operate in a calculated and intentional way.” Accordingly, Wells’s songs have a loop-induced structure, and their melodies are both meditative and playful.

The final track of Plant Music Vol. 1 consists of 20 minutes of quiet talking from Wells, inspired by Molly Roth’s early ’70s LP, Plant Talk. “The album is entirely spoken word, and the idea is to put it on when you don’t have the time to talk to your plants yourself—whether you’re going to class or ‘making love,’ as Molly Roth suggests.”

Katie Shlon

Play Some Songs to Make the Plants Grow

Cassette

The improvised sounds on Play Some Songs to Make the Plants Grow are inspired as much by the natural world as they are a response to it. They’re culled from a three-week road trip in 2015 that found Shlon—then a recent Art Institute of Chicago graduate working with a grant she’d earned from the University—visiting artist-built environments in the American West. With an old-school cassette field recorder, Shlon recorded live and uncut improvisations that would eventually become a dual-cassette release. “I spent a lot of time listening to already existing patterns of sound in each landscape and then slowly began playing along,” she says. “Considering the birds, frogs, wind blowing, everything really, as if they were other instruments I was improvising along with. The recorder even picked up the sound of the tape rolling, which ended up being an important rhythmic structure as well.”

The improvised recordings on Play Some Songs to Make the Plants Grow each feel unique, but the palette of guitar, found sounds, and tape clicking provide a consistent sonic palette. Shlon says these pieces—she’s hesitant to call them songs—deal with ideas of “structure, order, and disorder, and defining my sound work in my own terms.” It was the sites themselves that provided the shape and structure of her music. “These places are living and alive, and the presence of plants and flowers are a huge part of that,” she says. “For me as an Arab-American, I think I’ve looked to the landscape a lot for a common ground when I didn’t feel at home with the people or structures surrounding me.”

While Shlon sees her intended audience as plants more than humans, she relied on her own intuition rather than botany or horticulture texts. “There’s definitely no scientific basis surrounding this project at all,” she says. “Just, like, pure emotion. I think that plants have a healing quality, and working with the soil is incredibly therapeutic. I like the idea that you could be able to nurture and care for plants in a way that recognizes the fact that they are living beyond their basic needs of water, light, and nutrients.”

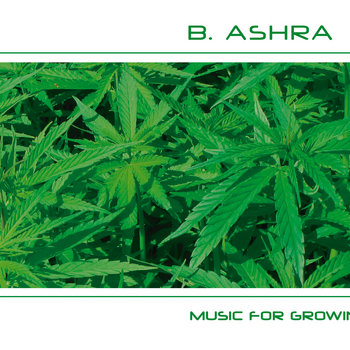

B. Ashra

Music For Growing

Compact Disc (CD)

Bert Olke moved from his native Northern Germany to Berlin in 1987, and spent his 20s playing industrial music but growing increasingly enchanted with electronic artists. He found techno in the early ‘90s, and “lived it,” he says, then discovered the ambient house music that was gaining popularity as a calming offshoot of more dance-minded electronic music. “I stayed more and more often in the Ambient Chill Out Rooms, and was musically very inspired there,” he says.

Olke has two musical personas, Robert Templa for his techno and B. Ashra for his ambient music. But he describes the songs he makes as the latter as covering a broad spectrum of music, “from very quiet electronic ambient meditation music to groovy spacious illbient/psybient to minimal techno.”

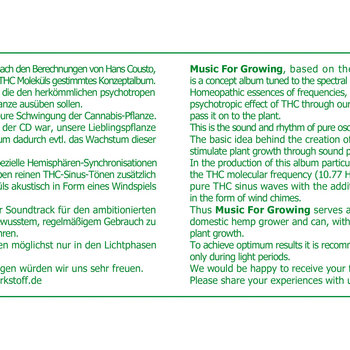

Music For Growing is a project issued by the esoteric Klangwirkstoff Records imprint, which Olke co-founded. The label’s expressed purpose is “exploring the effects of planetary and molecular tunings.” In practice, this means that Klangwirkstoff releases ambient collections that are meant to be sonic reproductions of plants, chemicals, or even entire planets (through an involved process called “octavation,” which you can read about here.)

In the case of Music For Growing, the idea was to replicate the active psychotropic chemical in marijuana, THC, which Olke says has a frequency of 10.77 Hz. Olke and friends hypothesized about surrounding cannabis plants “with their own molecular sound,” he says. He wondered if perhaps it would make the plants grow faster or make resulting drug more potent. “I thought of the plants but also of the growers, who would have to endure the sounds,” he says. “And I began to emulate the sound of the molecule as accurately as possible using the sound of a wind chime. So it’s music for plants and for people.”

The album, a continuous and “self-composed” 75-minute track with an oceanic and calming ambient sound, has one other aim—one that earned it a warning label about driving or operating machinery while listening.

“I tried to make the effect of THC tangible for the listener in the form of sound,” Olke says.

Jan Grünfeld

Music for Plants

German composer Jan Grünfeld recorded Music For Plants in three days, “on the huge balcony of an old villa in the middle of an English landscape park on the German-Polish border.” He improvised the music as it came to him, using mostly a loop pedal, an electric guitar, and an electronic bow. Bird sounds occasionally flare up in the background, but these songs are actually quite tense and cinematic. Grünfeld hasn’t played this music for humans, he says. “It is only for the patient plants.”

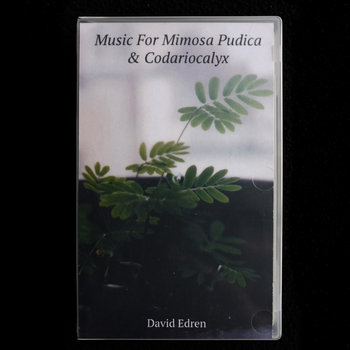

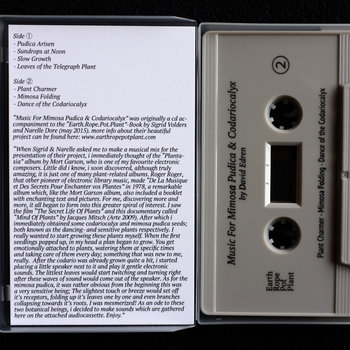

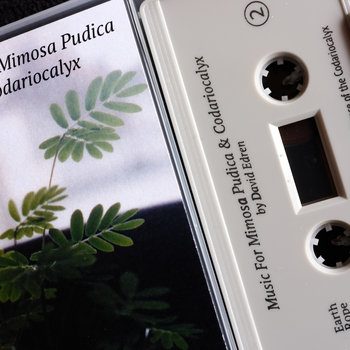

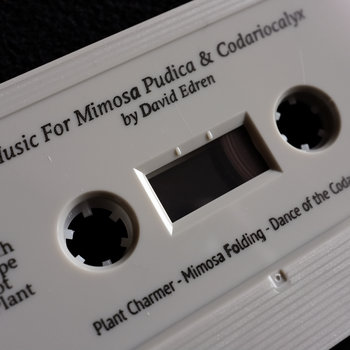

David Edren

Music For Mimosa Pudica & Codariocalyx

Cassette

Inspired by Mort Garson and library music pioneer Roger Roger, Belgian composer David Edran writes that he tested his compositions on plants he was growing. “After the codario was already grown quite a bit, I started placing a little speaker next to it and play it gentle electronic sounds. The littlest leaves would start twitching and turning right after these waves of sound would come out of the speaker,” he writes. “As for the mimosa pudica, it was rather obvious from the beginning this was a very sensitive being…” The genuine affection Edren feels for his plant audience is reflected in the album’s songs, which are largely adventurous and playful electronic lullabies.

Source Vibrations

Vibrational Growth for Plants

Source Vibrations is Asa Idoni, a Colorado-based composer, sound engineer, and mystic. Idoni is the prolific musician behind dozens of collections, most of which are in the realm of meditation or sonic healing. According to the Source Vibrations website, “Asa transcribes natural structures like colors, archetypes, and geometries into melodic patterns and harmonies, encoding them into sound.” Vibrational Growth for Plants, which sounds a little like a haunted rainforest to human ears, was created to assist plants with nutrient absorption.

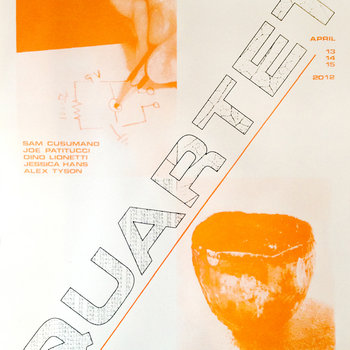

Data Garden

Quartet: Live at The Philadelphia Museum of Art

, Poster/Print

The title may make this album sound like a pretty standard jazz show, but the players here are what make the album really special. That’s Philodendron on lead synths, two Schefflera plants holding down the rhythm section, and a Snake Plant performing the ambient sounds and effects. The idea of four plants’ electrical impulses playing a “live” concert (with the aid of human computer programmers, of course) makes this two-hour, avant-garde electronic music the reverse of most plant music: It’s the music plants make for humans. It’s also hypnotic and transfixing. The fascinating Data Garden label is often on the forefront of human/plant relations. Case in point: If you plant and water their physical releases, they’ll grow!