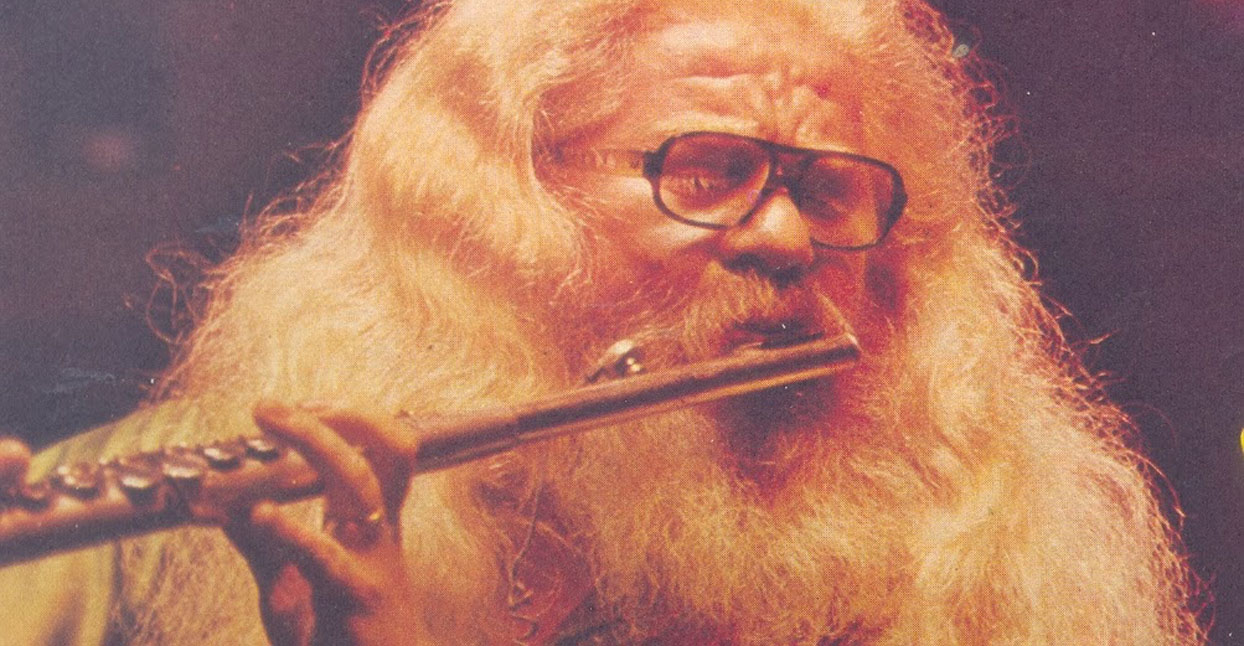

One of Brazil’s greatest musical sons, Hermeto Pascoal has forged a career on cutting free-flowing jazz with the groovy styles native to his homeland. Take it from Miles Davis, who once dubbed Pascoal “one of the most important musicians on the planet.” When the pair combined forces in the early 1970s, on Davis’s 1971 album Live-Evil, it was Davis who wanted to record the Brazilian’s songs and not the other way around.

An improviser with superhuman ability, Pascoal—almost always referred to as simply Hermeto—built arrangements that often stretched out to marathon-like running times. Everything he did flowed gracefully, despite a musical palette that included barnyard animal noises and household appliances.

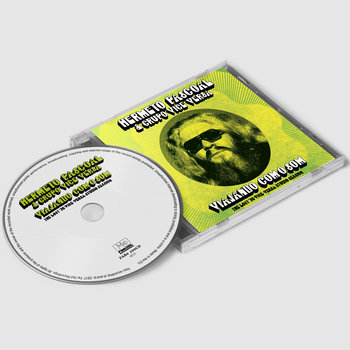

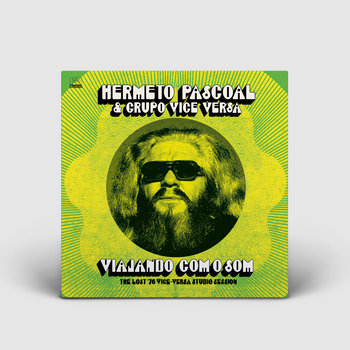

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Shirt

Pascoal’s talent was only matched by his striking appearance. With flowing white hair and a long beard, he could pass for a funky Santa Claus, or Lord of the Rings character Gandalf. It doesn’t take much to discover why his nickname is “O Bruxo,” (“The Wizard”).

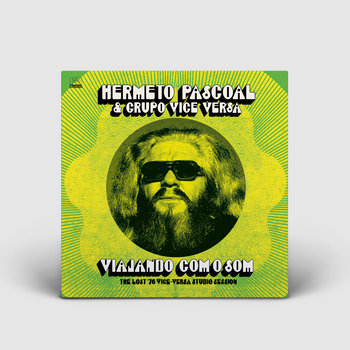

At age 81, Pascoal still works and thrives. But until recently, the public didn’t know that his unimpeachable discography was missing a key ripple. For two days in 1976, Pascoal and a group of his musicians worked at Rogério Duprat’s Vice Versa Studios in São Paulo on recordings that were unreleased for over 40 years. Now, Viajando Com O Som (The Lost ’76 Vice Versa Studio Sessions) has been recovered and released via London-based Far Out Recordings. For Pascoal’s fans, it’s an unexpected gift, rescued from a crack in time.

“To find a ‘lost’ album by an artist of the calibre of Hermeto—especially one with the unique line-up of musicians on Viajando Com O Som, whose output was virtually undocumented—is historically significant,” writes Far Out’s music lawyer and Pascoal fanatic Howard Livingstone via email. “In the same way that finding, say, a ‘lost’ Beatles album or finding an unknown composition by Bach or Mozart would be significant.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Shirt

For Zé Eduardo Nazário, Viajando Com O Som has been “lost” for too long. The drummer was a key player in Pascoal’s orbit in the early 1970s, but without a credit on any recordings, his position in the legacy was never laid out on the back of a record sleeve.

Nazário met Pascoal in the late 1960s, in the midst of Brazil’s authoritarian military dictatorship. Musicians weren’t always able to create openly, but there was a jazz club in São Paulo that served as a safe place for musicians to come together—CAMJA (The Friends of Jazz), a striking house that sat on the corner of Estados Unidos Street and Antihas Street.

Nazário arrived at the spot one night with bass player Itiberê Zwarg. “When we entered the club, it was a dark room,” he recalls. “An amazing piano sound came from that room. Me and Itiberê, we laughed, turned the lights on, and it was Hermeto playing the piano in the dark.”

The pair ended up playing a version of bossa nova legend Johnny Alf’s song “Céu e mar” with Hermeto, who had not yet cultivated his shaggy look. In their hands, the composition lasted an hour. Zwarg would end up spending a significant chunk of his career as a key component in Pascoal’s band.

It took a few years for Nazário and Pascoal to cross paths again. Pascoal soon traveled to the States, splitting time between New York and Los Angeles from 1970 to 1971. While in the U.S., Pascoal connected with Miles Davis through the great Brazilian drummer Airto Moreira, and after working on the jazzman’s Live-Evil record, Davis wanted Pascoal to join him on the road. The offer was declined.

“He just felt like, as much fun as he was having in the United States, for him to really express himself, he had to go back to Brazil,” says Andy Connell, a Professor of Music at James Madison University, who has spent significant time with Pascoal. “So, he went back to São Paulo.”

By 1973, Nazário snagged a visa to go to the U.S. and was preparing to leave for a music job in Minneapolis. Pascoal needed a drummer for a gig in the city of Londrina. Nazário, who was 21 at the time, decided to forgo opportunity in the States to perform with him.

“The next week, when I went to Hermeto’s house to get the money for the gig, he invited me to join the group,” Nazário remembers. “And so, I gave up my travels to the United States and I joined because my desire was to play with Hermeto. It was a dream to have that invitation. [It was] hard work every day, doing rehearsals and playing. There were not many concerts to do at that time, but eventually, we started to do gigs.”

It was during this period that Pascoal constructed the band heard on Viajando Com O Som. The rhythm section hailed from Sao Paolo, with Nazário on drums and Zeca Assumpção on bass. Nazário’s younger brother, Lelo Nazário, was recruited to play piano after catching Pascoal’s well-tuned ear during rehearsals.

“Sometimes, when they finished, I jumped onto the electric piano and started playing with my brother,” Lelo writes in an email. “I think Hermeto liked what he heard, so he invited me to join the band. I was 16 or 17 years old at the time. Playing with him was wonderful, because he’s very generous in sharing his knowledge and experience, and I have experienced an incredible feeling of freedom during the time I’ve played with him.”

From Rio de Janeiro, Pascoal recruited woodwind players Mauro Senise, Raul Mascarenas, and Nivaldo Ornelas for the recording sessions, along with guitarist Toninho Horta and vocalist Aleuda Chaves. Many of them went on to have fine careers in contemporary Brazilian instrumental music, but in the 1970s, they were just getting started.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Shirt

In São Paulo, the group convened for the two-day sessions that would become Viajando Com O Som, plus a third day when Pascoal and the Nazário siblings worked on the mix.

Zé Eduardo Nazário remembers the scene: “The instruments were in the room, we were together, there was no separation. It was a large room. The horns were there at the end of the hall, and my drum set, on the other side. The keyboard, in the middle. We had earphones and the set was made, just everybody playing together. I think that is very rare to see these days. It’s very ‘50s—everybody playing together, real jazz, no make-ups. The real thing.”

Viajando Com O Som reflects Pascoal’s musical ethos of the time. “Dança do Pajé” and “Natal (Tema das Flautas)” are orchestrated pieces with chiming harmonies, capturing the rootsy, organic feel that underpins much of Pascoal’s music. “Mavumvavumpefoco” and the 26-minute “Casinha Pequeninha” are more experimental tracks that incorporate atonality in certain parts. Pascoal continued to investigate that style on the 1977 release Slaves Mass, which is arguably his most famous album.

“‘Casinha Pequenina,’ in particular, shows Hermeto trying to capture the atmosphere of his live concerts for which he was well-known—long, extended performances with a lot of soloing and improvisation,” says Far Out’s lawyer Livingstone. “The group would play for hours at a stretch reaching ever-higher peaks of improvisation and intensity. Hermeto has since become famous for his free-following live shows with long improvised tracks.”

According to Professor Connell, the influence of Miles Davis on Viajando Com O Som is evident: “The looseness of what Miles was doing in the early ‘70s—a lot of Miles’s tunes are based on three chords, or a gesture or a phrase, and then spun out in these long jams. That certainly influenced Hermeto. There’s a lot more free playing recorded in his ‘70s work then you find in the ’80s stuff.”

While recording Viajando Com O Som, Zé Eduardo Nazario always figured he was working on a fully-functional album that would be released. But the record stayed in the can due to changing circumstances. Hermeto soon traveled to the States, where he recorded Slaves Mass and another album with Flora Purim, called Open Your Eyes, You Can Fly. On top of that, family reasons drew him to move to Rio. As a result, the São Paulo recordings became lost in the crush, and Pascoal’s travels effectively ended Nazario’s tenure in his band.

“It changed a lot, because we couldn’t go to Rio to live near Hermeto,” Nazário says. “At that time, he thought the musicians had to be near him to make what we made, to rehearse every day. My son was just born in 1976, and my first wife didn’t want to change from São Paulo—where we lived in a good place in the suburbs—to Rio de Janerio, where Hermeto bought his house. So we decided to keep living in São Paulo.”

When Pascoal’s interest in the project dissipated, the fruits of the Vice Versa Studio sessions may have been lost for all eternity. But as luck would have it, Lelo Nazário had his own copy of the recording.

“At the end of the mix, I asked the engineer to make me a copy of all the material—from machine to machine, at the time, the Ampex two-track recorder,” Lelo says via email. “As far as I know, the master tape eventually got lost over time, but I kept the copy in my studio’s archives for all these 40 years.”

Operating his own studio in São Paulo these days, Lelo was able to run some audio restoration on the recordings. Zé Eduardo posted a couple of tracks to his website about a year ago, which piqued the interest of music lawyer Livingstone, who pointed out the material to Joe Davis, the owner of Far Out Recordings. The label had a previous relationship with Hermeto, having released an album he produced for Aleuda Chaves called Oferando.

Davis reached out to Zé Eduardo Nazário to ask about the songs, whether there was any more material, and if he was interested in releasing it. “I told him, ‘Yes, of course but it’s not ours, it’s Hermeto’s group so you have to speak with Hermeto about it,’” Nazário says. “He did, and fortunately, it came to a very good end.”

The label went through Pascoal’s son, Fabio, to strike a deal. From there, Davis had the album digitally remastered by engineer Pete Norman, a veteran of Abbey Road Studios.

With the release of Viajando Com O Som, Nazário is pleased that one of the most important times in his life is finally on wax. “It’s a great album,” Nazário says. “You listen 41 years after, and you still feel the music is fresh. I think today’s music is more meticulous. At that time, it was more wild. It’s spontaneous combustion—like cannonballs.”

—Dean Van Nguyen