Bangalore-based Ketan Bahirat, who creates electronic music under the moniker Oceantied, was watching a dance troupe known as the Baane Mane Gopalpura perform the ‘Dollu Konitha’—a drum act native to the province of Karnataka—when inspiration struck.

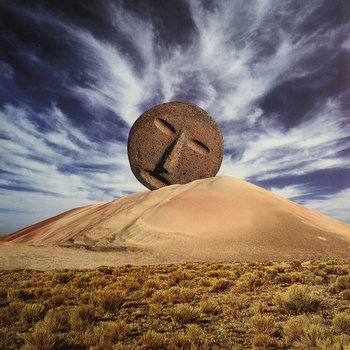

Boasting religious origins, the ‘Dollu Konitha’ is often staged for both entertainment and spiritual purposes. Performers sling a dollu drum — a type of percussion popular in Karnataka—around their neck as they play, leaving their feet free to dance. Their slow and fast rhythms transfix viewers, similar to the delicate balance between full and half-time tempos on Oceantied’s banger “Tribes.”

The number begins with haunting flute melodies weaving between steady intervals of beats that resembles the show’s dollu drums. Vocal cries then enter the mix; up to this point, the track resembles progressive or experimental bhangra. But shortly following the one minute mark, warped basslines kick in, and footwork fans know they’re in for something special.

Released on his debut 2016 EP of the same name, the song grew from being three minutes long to something longer and more meaningful, Bahirat says. “I was trying to channel the energy I felt while watching the Baane Mane Gopalpura act and add the essence of footwork [and] jungle.”

The graceful union of Indian sounds with the Chicago subgenre’s skittery tone—organic meeting electronic—can be heard throughout the four-track EP, which incorporates jungle as well as juke while teeming with influences from his home country, in the form of field recordings and instrumental references. “I’d record small percussion stuff on just my phone, dig for samples online, and just throw them on to Ableton and try painting a picture of what was going on in my head,” he says.

On the subsequent song “Streets,” undulating drums are interspersed with a jingle that mimics ghungrus—an anklet of tiny bells usually found on the feet of Indian classical dancers. Around the 1:30 mark, listeners hear an Indian man issuing a concerned warning about “dangerous sounds”—a sample that adds comic relief and helps transitions the record into whirring, twitchy bass. “‘Streets’ was made as part of an exercise I do with a music collective I’m a part of called DASTA, where the six of us put in one sample each and make a track within a week, all the samples just fit in perfect and had an Indian element to them already,” Bahirat explains.

A key flag-bearer of underground electronica in the world’s largest democracy, the artist is an RBMA graduate and was a headliner in Boiler Room’s first-ever India session last year. Since then, he’s shared decks with high-BPM dons such as RP Boo, Sam Binga and AMIT. This past year was a busy one for the young gun producer, with his second EP, Paradise/Closets, due out in the fall.

Expanding more on DASTA’s goals, Oceantied explained the group’s goal is to create a real community for music-makers all across India. “When we were deciding what exactly to do, we held a self-imposed residency at Alibaug for a week, close to Mumbai at a farmhouse, where we built two studios, and basically used it as a point to discuss events, plan for the year and create a pool of ideas,” he says.

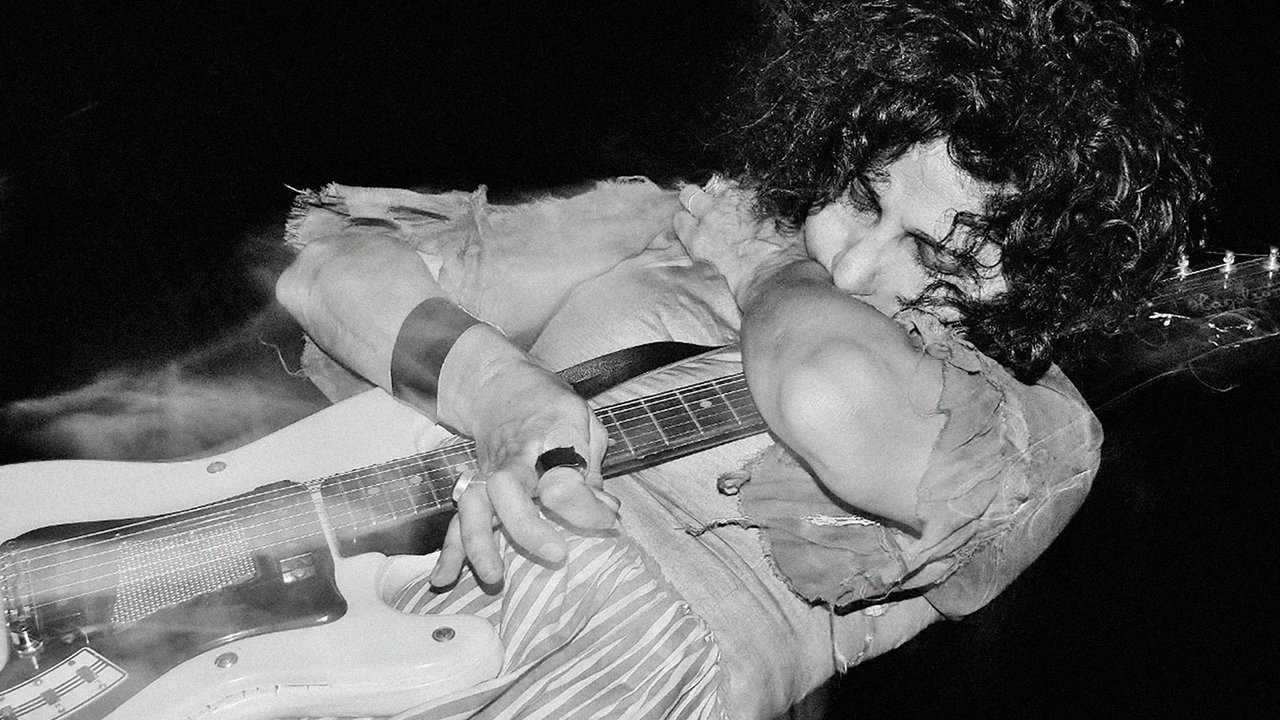

Bahirat, who is also a guitarist for post-rock band Until We Last, boasts a deep relationship with India’s centuries-old rhythmic traditions. “I grew up listening to a lot of Indian classical music because of my dad.There was music being played every morning as I woke up, and I think that influenced me a lot when it comes to making music,” he says. “I also went for Hindustani Classical vocal lessons for a year, did the basics, bought myself a guitar and that’s basically how I got into making music, I taught myself how to play and, later, record.”

Despite all the nods to Indian culture, Bahirat insists the Tribes EP was more of a simple creative release than a concept record. After musing a bit on the power of Indian folk music and how he interprets those sounds, he concludes: “I wanted to use all the influences that I’d gathered and put my own soul into it.”

Footwork in the South Asian nation remains very much a niche scene for now, but Bahirat is positive about its future. “I think the sound is easily appreciated in India because of the energy,” he says, “and also because it’s a relatively fresh sound for our audiences. The footwork parties nowadays are doing really well, but DJs will usually mix in jungle [and] drum n’ bass, too. We’re still yet to see dancers. The listener base for footwork is growing rapidly, though; lots of young producers are inspired by the movement, and there’s only upwards to go with that.”

—Nisa Kreems