In Simon Reynolds’s seminal book, Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, the author suggests punk, “had its most provocative repercussions long after its supposed demise.” If there was one group that reinforced Reynolds’s claim, it was Bristol, U.K.’s Maximum Joy, whose influential yet primal sound fused dub reggae, free jazz, funk, disco, soul, and Afrobeat into a heady post-punk brew.

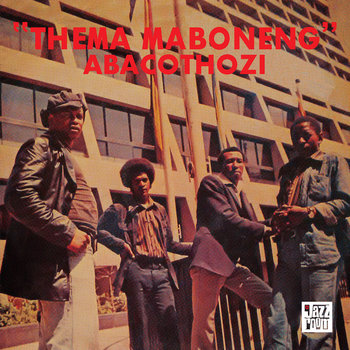

With its close ties to local contemporaries The Pop Group and Pigbag, Adrian Sherwood’s dub label On-U Sound, and 99 Records’ ESG and Liquid Liquid in New York, Maximum Joy is pivotal to the history of post-punk. Yet until now, the group has been a footnote in the narrative, with just a brief mention in Reynolds’s otherwise thorough book. I Can’t Stand It Here On Quiet Nights, a new compilation on Silent Street, aims to right that wrong. It combines the three EPs Maximum Joy recorded for Y Records in 1981 and 1982, acknowledging the group’s rightful place in the post-punk canon as pioneers of the Bristol Sound.

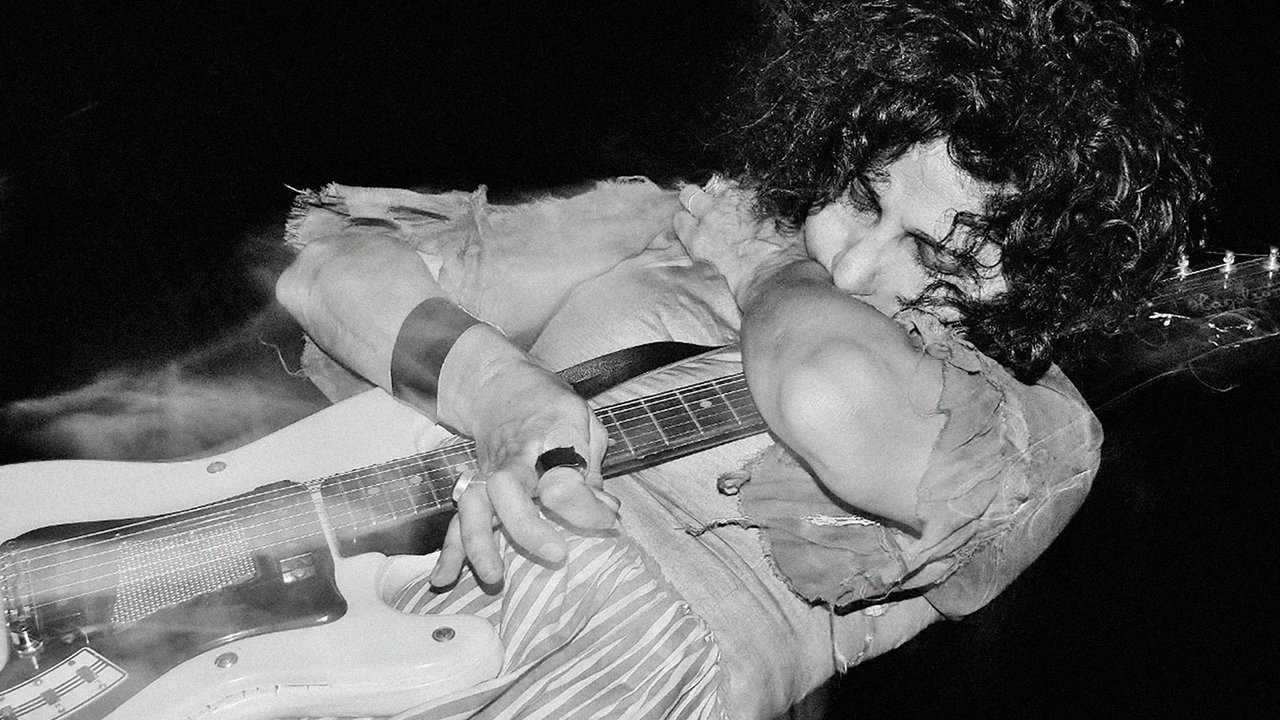

Maximum Joy formed when 18-year-old photography student and aspiring singer Janine Rainforth met saxophonist Tony Wrafter, who had just left Glaxo Babies, one of England’s more cultish post-punk bands. The two bonded through a love of music from the outer limits, born from days listening to Can and Sun Ra records at Revolver Records.

While London punks learned about Jamaican music under the tutelage of DJ Don Letts at The Roxy, their Bristol counterparts experienced reggae bass and riddims at sound systems like Enterprise Imperial Hi-Fi and Froggy’s Excalibur. The inner suburb of St. Paul’s throbbed with the pulse of reggae “blues” parties at spaces like the Ajax, Blue Lagoon, Trinity Centre, and Black & White Café.

“In those days in St. Paul’s, there were blues parties and sound systems pounding out the heavy dub music everywhere, on every corner, and it was non-stop 24/7, man,” Wrafter recalls. “The blues parties were phenomenally important both for me and for Maximum Joy,” Rainforth adds. “They were womb-like experiences and left a great impression.”

Equally formative was The Dug Out club on Park Row, a melting pot where punks and the soul/funk crowd mixed freely with Rastas, students, and other outsiders. “The Dug Out was a great place for us because of all the different types of music they played—mainly funk, soul, and reggae at that time,” Rainforth says. Also regulars at the Dug Out and the St. Paul’s blues parties, The Pop Group—like Glaxo Babies before them—eschewed the three-chord crash of punk on their groundbreaking LP, For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder?

But when these two pioneering groups started to fracture, Maximum Joy emerged. Joined by Glaxo Babies’ drummer Charlie Llewellin and the Pop Group’s Dan Catsis (bass) and John Waddington (guitar), Wrafter and Rainforth formed the unit against a backdrop of social unrest.

The inner city riots that would ignite the U.K. the following summer—from Toxteth in Liverpool, to Brixton in London—were sparked in St. Paul’s in April 1980. Years of police harassment, unemployment, poor housing, and Margaret Thatcher’s controversial stop-and-search laws finally came to a head when police raided the Black & White Café on Grosvenor Road.

“We lived on the next street to the Black & White Café,” Wrafter remembers. “We have to thank the West Indians for their stance, but there were nearly as many whites as blacks involved in the running battles with the police. The whole of Montpelier in St. Paul’s was taken over for about three days—the police couldn’t come in.”

It was within this volatile climate that Maximum Joy began to create their sonic response to Thatcher’s Britain. “The name Maximum Joy came from this exuberant feeling I had at the time, despite all the shit that was happening around us,” Wrafter says. “I’d done a track with Glaxo Babies on our second LP, Nine Months To The Disco, called ‘Maximal Sexual Joy,’ so it came from that. And I thought Maximum Joy just sounded great.”

Dick O’Dell, who managed the Pop Group and the Slits at the time, set up Y Records when the two groups defected from their labels. Best known as home to Pigpag and Shriekback, Y Records released a broad range of music, from dub disco to jazz. The label epitomized the creative free spirit of the post-punk era and would be the perfect home for Maximum Joy’s own explorations. “I’d met Dick through my work with The Pop Group, and also the Slits who I had toured with,” Wrafter says. “I told him I had some stuff coming up with Janine [Rainforth], and he came along to the studio and was really excited by what he heard. He ended up mixing ‘Silent Street.’”

Wrafter wrote “Silent Street”—for Maximum Joy, with Rainforth—while living at 12 Campbell Street in St. Paul’s, by the back door to The Black & White Café. “Because we were surrounded by dub every day, we never really thought, ‘Let’s do a reggae song now.’ It just happened,” says Wrafter.

The debut single was recorded at the infamous Berry Street studios in London. “I’d first been to Berry Street before to play on a track called ‘Strange Things’ with the On-U Sound group London Underground, so we knew what a great studio it would be for us,” says Wrafter. In the late ‘70s, Berry Street had been home to punk bands like the Raincoats, Slits, and Mo-dettes, as well as experimental post-punk groups such as This Heat, Flying Lizards, and Family Fodder.

By the early ‘80s, Sherwood was recording his early On-U Sound dubwise experimentations there. He invited Wrafter to play on LPs by Singers & Players and African Head Charge, whose My Life In A Hole In The Ground LP was inspired by the basement studio. “The studio was deep underground, and with these thick walls around, it had a great resonance,” Wrafter says. “For reggae especially, it sounded really good.” The early sound of Maximum Joy also owed much to the equipment at Berry Street, such as the Roland RE-201 Space Echo and a huge Neve mixing desk. “It was all analog equipment and there was plenty of room for everyone to get involved when the mixes were being done,” Wrafter says.

The A-side, “Stretch,” was an urgent, agitated slab of raw punk-funk that allied them with New York’s ESG. “We all loved Chic and things like Funkadelic, so you can hear that especially in the bass and guitar,” Rainforth recalls.

Like other New York no wave artists James Chance and Bristol counterparts Pigbag and Rip Rig + Panic, Maximum Joy also heard the future in the liberating sound of free jazz. “Archie Shepp, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Pharaoh Sanders, and Sun Ra were really influential and we used to listen to them a lot,” Rainforth says.

As a singer, Rainforth was inspired by everything from Billie Holiday to African throat singers, but created her own style to match the urgency of the lyrical content. “The lyrics to ‘Stretch’ were just about being positive really, stretching yourself to the limit, and seeing no boundaries despite the morale of people being really low,” she says. “I wrote it at a time [when] we had the Cold War hanging over our heads, there were all the national strikes, Thatcher’s government was in power, and the St. Paul’s riots went on in our area. We felt we could affect change with our music, it was a way of expressing ourselves and having a freedom in those times.”

It was also a time when women were coming to the fore, challenging the previous rock music model. “It was a brilliant time; people like Poly Styrene [from X-Ray Specs], Ari Up [from The Slits], and Lizzy Mercier Descloux were a great inspiration to me,” Rainforth says.

Maximum Joy were soon affiliated with the hip New York scene when Ed Bahlman signed them to his legendary 99 Records. The label had just released the first singles by ESG, Liquid Liquid, and Bush Tetras, and the cross-pollinating sound of Maximum Joy made perfect sense for New York’s no wave scene. “That was pretty exciting when our single was released on 99 Records, and our tunes started to become underground hits in clubs like Danceteria,” says Rainforth.

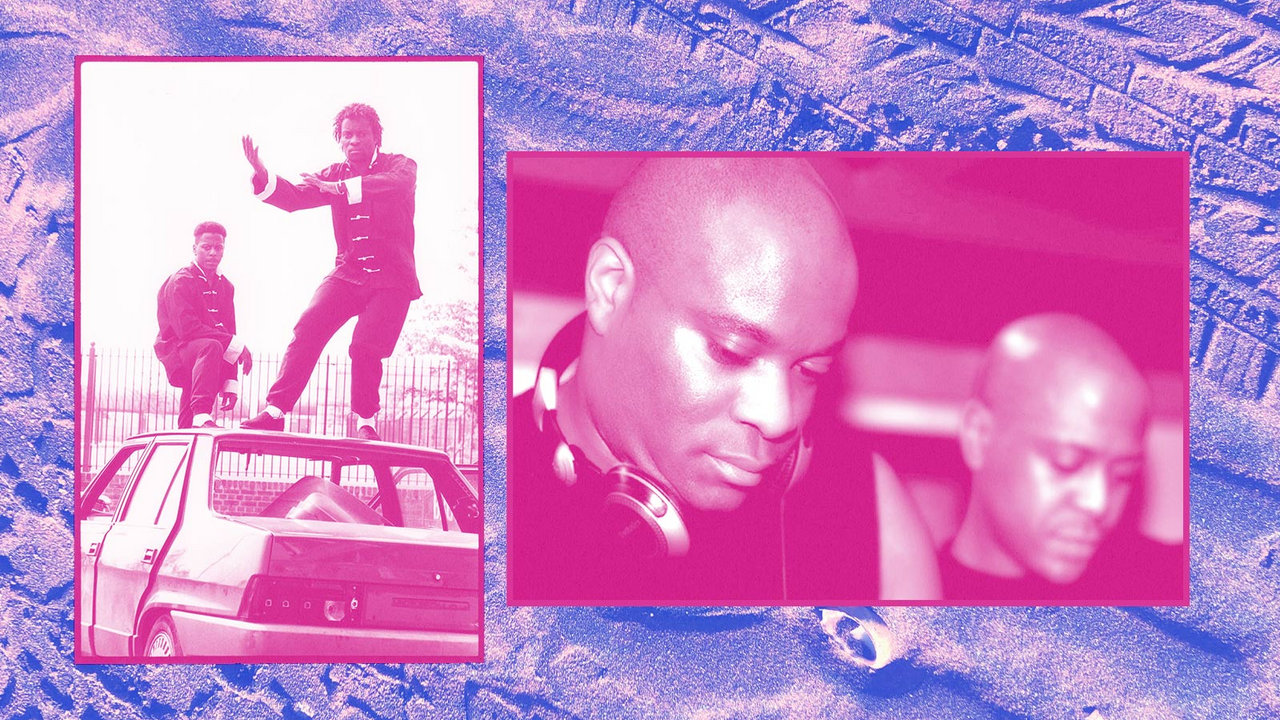

Connections to New York were solidified when the 99 Records EP reached DJs at pivotal hip-hop station Kiss FM. “Simon Underwood came back from playing with Pigbag in New York and told me they were playing ‘Silent Street’ every night,” says Wrafter. Back in Bristol, DJs at the Dug Out (including future members of The Wild Bunch that would mutate into Massive Attack) would spin the 7” next to funk, disco, and early hip-hop.

Also recorded at Berry Street Studios, the group’s second single, “White and Green Place,” was released in 1982. “I wrote that song about the soullessness of things and places,” says Rainsforth. It found the group mining their love of jazz and African music to create a wonderful slice of mutant disco. But their explorations of space and echo reached its zenith on the 12” expanded Extraterrestrial mix of “White and Green Place” and the B-side, “Building Bridges/Building Dub,” found on I Can’t Stand It Here On Quiet Nights.

Maximum Joy’s only LP, Station M.X.J.Y. (named in tribute to the NYC radio stations the group heard on early hip-hop mix tapes) would be recorded later that year with producer Adrian Sherwood at the helm. “It was great working with Adrian,” says Rainforth. “His production is so unique and beyond.”

The group returned for one last single, a dubbed-out version of Timmy Thomas’s “Why Can’t We Live Together,” released on Garage Records in 1983. Produced by Dennis Bovell, and featuring a young Nellee Hooper on drums and vocals, it would be a fitting end for a group born around the blues parties of Bristol. The same streets and clubs that birthed Maximum Joy soon exploded with a new musical movement—dubbed the Bristol Sound—which also emerged from The Dug Out through groups like Massive Attack and Smith & Mighty.

In 2015, Maximum Joy reunited to play Bristol’s Simple Things Festival and London’s Lexicon. “There’s been a lot of activity behind the scenes since then,” Rainforth says, “and this reissue is just the start of it.”

—Andy Thomas