In 2012, a little video game called Hotline Miami was released on the distribution platform Steam, developed by the unassuming two-man Swedish team Dennaton Games. HLM, as the game is often abbreviated, utilized a lengthy 22 tracks of directly-sourced electronic music, which sometimes echoed the violent aural sensibilities of Nicolas Winding Refn’s film Drive. In terms of pure Steam users, HLM has over two million installs at the time of this writing, and its design and audio are considered indelible inspirations to indie games for the past five years.

Hotline Miami is a pixelated, ultraviolent, surreal thriller and score-attack game, rich with pulsing dream imagery, mythic coked-out ‘80s Miami aesthetics, Lynchian mystery, and laser-colored viscera. A “Game Over” screen can appear in as little as several seconds, as most every character in each level can be killed with one hit—including you. On restart, a selection from its soundtrack—sometimes by design, but often chosen at random—will kick in, fueling the slaughter.

Vinyl LP

There’s a reason that the word “soundtrack” autofills when you start typing the game’s title into most search bars: there’s something fascinatingly infectious about these songs, which accompany the game’s intense difficulty and manic progression, recalling the Pavlovian manner in which gamers once memorized the tracklists to Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater or Jet Grind Radio.

Since HLM and its sequel, several of its featured musicians have gone on to considerable success on their Bandcamp store pages and beyond (Bandcamp, curiously, is also where Dennaton first discovered them). Artists like Perturbator, Carpenter Brut, Scattle, El Huervo (aka Niklas Åkerblad, who also contributed some key art and design assets for the series), and others have all continued a career in music supercharged by the game’s release. You could even argue that publisher Devolver Digital owes its increasing growth to the catalytic success of HLM. But, notable, four of HLM’s 22 tracks come from the self-titled debut EP from M|O|O|N—the only musician to have his entire release presented in the game.

M|O|O|N, or Moon, or M.O.O.N., or Stephen Gilarde, is a young man from Boston who makes electronic music—and he’s getting better at it. A few humble tracks made at the start of his career six years ago have each generated upwards of three million plays on YouTube, creating a quietly rabid fanbase for a mysterious individual whose moniker can be a pain in the ass to reliably Google. That his music soundtracked HLM is crucial: gamers alone have listened to M|O|O|N’s first EP many millions of times without even clicking a link.

Since then, M|O|O|N’s music has flourished beyond the somewhat sparse selections on his debut. The essential components—driving percussion, nonlinear refrains, menacingly evolving melodies—are still around, but his subsequent releases boast something more complex and involved than those minimalist origins, aligning more distinctly with his key influences.

Vinyl LP

“I got into Daft Punk very early on,” Gilarde says. “I remember someone gave me a .zip of their entire discography, from [their early band] Darlin’ to Discovery, including all the Roulé [label] stuff Bangalter did, every live performance that was out there, remixes, the whole thing. That really got me. I think for people my age in America at the time—early-to-mid 2000s—Daft Punk was the gateway drug of electronic music. House music hadn’t made its way to pop music yet, techno wasn’t easily accessible—at least in small town Massachusetts—but Daft Punk were massive. Everyone knew them. That led me to a lot more French electronic music: Justice, Ed Banger records, Jean-Michel Jarre, etc. That was my intro. I weirdly had to work my way backwards to American dance music; I didn’t get into Detroit or Chicago until a bit later.”

M|O|O|N’s music is grounded in Parisian electro, funk, new disco, and house, but combines emotionally searing pads with pared-down vamps, frequently of the 8- or 16-bar variety. Earlier releases fixate on these serpentine measures, often in an approach somewhat similar, but not exact, to 5/4 timing; this sensibility gives songs like “Plus Four” a kind of “off,” or melancholic feel, and even when a beat keeps a rigid four-on-the-floor, the loop never nestles precisely on the first bar. His chord progressions skip a few stairs here and there, stumbling before straightening out. This complemented the frenetic, twitchy action game in a remarkable and unusual way, helping better signal the protagonist’s unreliable narrator role. The beat structures and timing he employs can be rigid and sometimes formal, especially early in his career, but the refrains and the vamps along this backbone are always just a little over-full, sloppy and skittery, just a bit “not right.”

“There’s honestly not really anything deliberate about how I make music,” he says. “I’m not trained, other than a few years of middle school band. I can’t really play an instrument, and I don’t know shit about music theory. A lot of the reason my stuff was so minimal and loopy, especially at the beginning, was simply because I didn’t know how to do anything more complicated than that. I’ve obviously learned a lot more since, which has lead to a bit of a complicated relationship with my older stuff.”

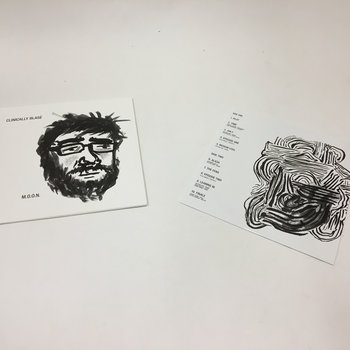

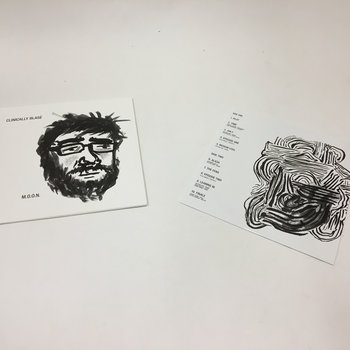

M|O|O|N’s new full-length record Clinically Blasé now stands as a bookend to his career; on June 23rd, a little over a month from its release, he announced that it would be the final recording for music under this name. It’s a surprise, since the album shows Gilarde at the peak of his abilities, retiring at roughly the same time his grasp on a musical vocabulary seemed firmest.

Vinyl LP

“I didn’t really feel like I had a voice until a few years ago,” he says. “I was still largely flying blind, mostly trying to replicate others’ styles, and jumping around a lot, trying to figure out what I was really trying to do. After the third EP, I really began to feel the need to do a proper project, to put the work in and try to be forward-thinking instead of reacting to what was around me musically. So I made a record: 11 songs, 53 minutes…it was trash. I deleted it. I guess ‘trash’ is the wrong word, but it wasn’t me. I was still figuring out who I was both musically and personally. That was the biggest lesson I learned in all this, that no one really knows what the fuck they’re doing, and people who stick to a very specific formula for making music aren’t actually that impressive, they’re mostly lazy and scared of deviating.”

Withdrawing from the project for newer (and presently secret) pastures is certainly one way to quiet any accusations of laziness, although the HLM fan’s insistent requests for more of the same created for Gilarde a familiar musician’s dilemma: the rejection of growth, of new artistic exploration and experimentation, in favor of crowdpleasing. Gilarde’s attraction to musical risk was only further complicated by his young success and notoriety.

“For the first EP, I had no idea what I was doing. It was all just blindly feeling,” he says. “That was fine though, because I didn’t think anyone would really hear it anyway. Now, people will send me messages like, ‘I miss your old stuff,’ or, ‘Why don’t you make stuff that sounds like XYZ anymore?’ I want to grab those people by the face and scream ‘A kid made that stuff! It’s so simple! There’s nothing groundbreaking about any of it! I was just trying to do what the people I listened to were doing!’ It’s tough for me to reconcile the popularity of my old stuff with how I feel about it. I’m almost embarrassed about some of it.”

Even his Facebook farewell post remains dotted with fans thanking him for that first EP, with nary a specific mention of Clinically Blasé. But there’s a reason Clinically Blasé features a brushed representation of Gilarde’s face on the cover—the record feels like a defining statement, and a full-on reveal of the artist who made it. His extended riffs and phrases have returned, but they’ve been expanded into record-spanning motifs. Where originally they would live on an island yammering at their only companion—usually a persistent house or disco beat—on Blasé they have risen to overture, grandly dramatic piano progressions that fold into synth pads, joined thoughtfully by anecdotal skits on the tracklist. The moves are more in-your-face, which makes the record feel significantly less lonely, shot through with confident yearning, the realization that the artist has a better idea of what he wants out of his machines in 2017.

Vinyl LP

“My music is exactly as complicated as I know how to make it, I suppose,” he says. “The more I learn, the more involved it becomes, and there is never any intent one way or the other in terms of being overtly weird, or intentionally minimal.”

“Alicia” first appeared as an expanded single in March, supplemented with some remixes (notably one by The Juan MacLean); on Clinically Blasé, it’s cut by three minutes and planted in the center of the record. M|O|O|N shaved down the original single to fit onto a 12-inch, but waved off any insinuation that there was artistic reasoning behind this; the edit was simply subject to the restrictions of vinyl length. The song’s sultry vocal sample swirls, falling somewhere between mantra and house-female-vocalist hypnosis. It feels like the next local train stop on a journey that began with the much stiffer and darker “Case Logic” from the Day/Night EP. Both songs make use of a repeated vocal loop; on the former, it’s “light the way”; on the latter, it’s “when the sun goes down.”

Aside from this callback, every track on Blasé is busier, and incorporates new ideas. The skits “Episode One” and “Episode Two,” which seem to be surreptitiously recorded on a cab ride in Austin, TX, include ambient air and sound, an accompaniment to the journey of a taxi drifting through a city before dawn.

Near the end of Clinically Blasé, there’s an emotional shift. It starts in “The Fens,” where a driving bassline that recalls Mirwais serves as the spine for a series of scales played on a piano and buried in the back of the mix. A drummer is keeping time, but the individual playing the piano seems to be finding their own murmuring sense of the world. They are sad and a little unsure, but keep ruminating on those scales, which bleed into “Episode Two.” No one has informed the pianist that their percussive accompaniment is gone.

Vinyl LP

This all leads into the mightiest, most determined, and most satisfying moment in the record: the slinky, rapturous burner, “Leaning In.” Bursting with movement, rambunctious energy, dramatic pauses and flourishes, but strangely dark and dangerous, it’s a fitting soundtrack for the best worst decisions of an evening. Infectiously danceable, with four kicks affixed to the floor, the song also peeks behind the scenes of M|O|O|N’s creative process, with a brief two seconds of atmospheric studio room air as his gear audibly turns on.

With his recent announcement, that equipment turns off—for now, at least. Whether that’s to score movies under a playful French pseudonym or lead a brass band in Berlin, nothing is certain. I like to imagine that the emergence and exposure narrated by Clinically Blasé is formative rather than misleading, and that the final years as M|O|O|N might represent something of a camouflage to Gilarde’s plans—work that was always intended to be discarded.

Or, as he puts it: “It’s the deviation from the straight ahead that interests me.”

—Leonardo Faierman