Markus Milcke

Markus Milcke

Explorer, music archivist, curator, and amateur ethnomusicologist Christopher Kirkley has spent much of the past decade documenting the sounds of the Sahel region in Africa, which encompasses parts of North and West Africa, and spans from the Saharan desert to the savannas of Sudan. Kirkley started Sahel Sounds as a blog during his initial trip to the region, a way to share recordings he made in the field, as well as music he collected from the countries he was visiting. The blog eventually became a record label, releasing compilations of music from cell phones, movie soundtracks, and, most recently, Gao Rap, a compilation of hip-hop from Northern Mali.

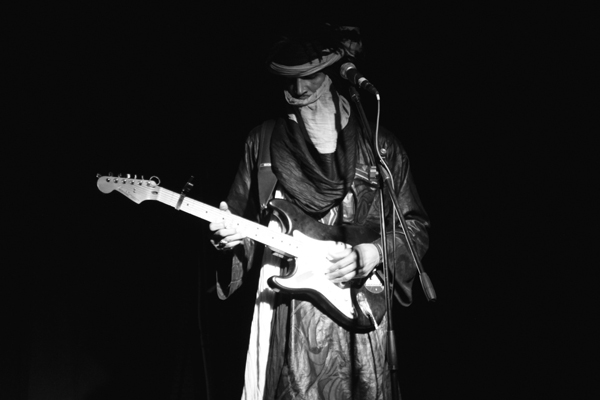

In addition to releasing compilations and albums, Kirkley is also a filmmaker. His 2015 album, Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai, is a remake of Purple Rain set in the Sahara, with Tuareg guitarist Mdou Moctar in the Prince role. And while he’s currently based in Portland, Oregon, Kirkley continues to make regular trips to Africa to connect with artists, inviting them to tour and record in the States.

We spoke with Kirkley about his role in the process of cultural exchange, and how it’s shifted with the growth of the Internet across the continent since his first trips. We also discussed the idea of dialogue between cultures, both across the Atlantic and between ethnic groups within West Africa.

I wanna start by diving into your origin story. When you first went abroad to record music in 2009, how long was that trip?

I wanna start by diving into your origin story. When you first went abroad to record music in 2009, how long was that trip?

Ahh, it was about a year and a half.

That’s long. You were living in Brooklyn at the time. Did you give up your apartment and everything and just head over?

Yeah. I was living in New York, but I had already sort of been on the road. I traveled in Brazil for a year, and I hitchhiked across the U.S., and I was living in a really tiny matchbox apartment in Bed-Stuy that I shared with a bunch of other musicians. I wasn’t working a nine-to-five in Manhattan or anything. I was already kind of on the road at that time. I went over on a one-way ticket and was just traveling. I didn’t really have a return date in mind.

How did you find music and people to record during the trip? How did you plant yourself in the culture?

I had a guitar with me on the first trip, and that was my passport into the world of musicians, because I was considered to be a musician. That enabled me to meet a lot of people. I would regularly be stopped walking down the street by other musicians because they saw me carrying a guitar said, ‘Hey, I play music too. We should hang out.’

What was your intention with these recordings? You’re cataloging, you’re taking record of this music. Did you have a plan of what you would do with it at that point?

I didn’t. I was just interested in the experience of recording and the experience of being present, of being there for the music. The blog I ran at that time was really just to provide some sort of documentation of my experiences, and also to offer the musicians something in return for the recording, because I didn’t have a label and I didn’t have a financial arm. I couldn’t just travel around and hand out money for people’s recordings. But I could offer them, ‘Hey, I’ll put your music online, I’ll have your contact information, and if somebody sees this blog post and says I want to work with this musician, I’ll put you in touch with them.’ And for a lot of musicians who didn’t have anything on the Internet, that already was a big advantage.

Did you ever envision that it would become the mammoth project that it is now? Or did you think, ‘This is my year and a half, and I’ll put everything on the blog but leave it at that’?

I was interested in the idea of working in culture, but never to the extent that Sahel Sounds would turn into a label, and become an ongoing project. In a lot of ways, I’ve been a victim of assumed success because every year the label’s gotten more attention and it keeps pulling me back in. So it’s continued but it was never planned.

How has the landscape of music and Internet changed between that 2009 trip and now?

There have been huge changes, primarily in terms of the availability of the Internet across West Africa. Cell phones were big in 2009, but now all those cell phone networks broadcast Internet. So anybody who’s in the cell phone network now has Internet. And everybody is on Facebook, everybody’s connected. It’s definitely changed. In general, the Internet changes everything. But for the musicians, it opens up a two-way street of not only being able to share their music, but also to hear more global music and to hear what else is happening.

You can see the impact in the music that people are making—particularly choir musicians. If you consider something like the choir music genre in West Africa, not a lot of people are making money off of albums or touring. But now that everybody has access to the Internet, the tours that an artist goes on, the shows they play, an interview that they might have on Dutch television, all of that information is coming back into Niger. So if you’re a star abroad, you’re a star at home. It’s all part of the same network, does that make sense?

Yeah totally, it’s like a feedback loop. The latest compilation, Gao Rap, was clearly influenced by Western hip-hop. How are musicians over there hearing that music? Is it strictly through the Internet, or are there stations or clubs playing that?

I mean, DJs definitely play Western hip-hop, and Western hip-hop has been a huge influence in West Africa. It’s hard to find a place that’s not been impacted by hip-hop. It’s kind of an embrace of youth culture wherever you go. So it’s not necessarily new, but at this point in West Africa, people know about the music.

I was in Cuba, which obviously has no Internet whatsoever, but the music that was playing over there was either 20 or 25 years old, or a couple select Rihanna songs. It’s always interesting trying to figure out how these songs got across. What do you think it is about hip-hip that so many different cultures and countries latch on to it?

Hip-hop is identifiable for a couple reasons, but in West Africa there’s always been a tradition of rhythmic, vocal music. Even if it’s instrumental, or completely a cappella there’s poetry that has innate rhythm structure that lends itself to hip-hop. And so every single little group I’ve ever been to, every ethnic area, everybody says, ‘Oh yeah, we invented hip-hop,’ because they check it out and show me some traditional music that has a very strong rhythmic structure.

It’s so interesting, the influence and impact of West Africa in general because if you look at, say, the origin of the banjo, it too stems from West Africa. Things like trade routes—do you think that’s what has carried so much of West Africa throughout the world?

Well, that’s one thing where it’s hard to say what the direct link is—ethnomusicologists have been professing this for hundreds of years, right? So when we do look at some contemporary music, like hip-hop or even Malian guitar, it’s hard to tie it when we don’t live in a vacuum. Ali Farka Touré was listening to B.B. King when he was writing his music. And so I think it’s a dialogue. Move music over here, and it comes back in a different form—there’s this conversation that’s happening.

To get a little bit deeper in that since you’re mentioning how it’s like a dialogue: How does cultural appropriation figure into this?

Discussions about cultural appropriation and politics of music and whatnot, the conversations that we have about this here in the West are very much Western conversations. They’re very much tied to place, and it’s very hard to break out of that and apply it in West Africa. For example: In Mali, there’s like 80 languages, so when we talk about the Sonrai music of Ali Farka Touré and the Tinariwen guitar of Tinariwen, we don’t talk about appropriation. But the Tinariwen guitar is very much influenced by Sonrai guitar. So did the Sonrais appropriate the Sonrai music, or is it a dialogue between the two? And so some of the ideas of appropriation often are framed in the context of the West versus the other places, and when you get into the specifics in West Africa it’s kind of breaks down, or it demands a whole other way of analyzing it. Which I don’t think anyone really has done.

How do you view your role in the context of cultural exchange? When you started it was a means of like, ‘I can record this for you, you’ll have the recording, you’ll also have a little presence on the Internet’. Now have a label. How do you think your role has changed?

The nature of the label is always going to be something that changes, and it’s not set in stone, and I can’t really make steadfast rules about what the label does versus what it doesn’t. At the very beginning I had a very hands-off approach—that I would just record music as I found it. Now, I play a more active production role sometimes. On the Luca record, for example, it was sort of like a mock New Age record, and that’s something I’ve definitely brought to a producer and said, ‘Here’s some music, let’s try to build something out of this.’ I also think that in terms of the relationships with artists, I adapt and change the label based on autonomy that the artists want to have. With certain artists, with certain groups, I act as the manager. So I release records, but I also handle the tours, and I handle the design of the record cover and everything related to that. As the Internet has gotten more accessible and the artist has the chance to have more of an input, I can step back and allow artists to take over these responsibilities. If an artist can be their own manager, and drive around on their own tour, and design their own record cover and the artwork, then I’m more than happy to act in that way. Because, at the end of the day, I want to be that label that helps their artists bring their music to a Western audience and be a platform for the artist.

You also have a new film coming out. What can you share about that?

It’s a film shot in Agadez, and it mixes Tawarikh folklore with contemporary issues of immigration and trans-Saharan issues, particularly in Agadez. It centers around a young man’s search for this lost city in the desert that’s rumored to be full of riches. It’s largely unscripted. It was a film we shot with a group of people in Agadez, but it was sort of a workshop where I brought this idea, but then we developed it together. I recently had the actor who plays the protagonist in Portland doing post-production with me as well and scoring the film. So in the end it’s going to be a very musical film—a lot of it is just images with this big score that he created. It’s not really about music, but it is a musical film, and it carries on the tradition of the label and the project of Sahel Sounds in that it’s a cultural object that we’re both creating together.

We also have a lot of different record projects, and those are constantly streaming out. I try to get a record out at least every other month. We’ve got a release coming from Mdou Moctar. Were able to do some really fun solo recordings when he was here in Portland recently, where he multi-tracked a lot of things, and got to play around with that. It’s kind of like his Beatles album—everything has four simultaneous vocals on it, it’s really far out. Next year, we’re going to be working on another film, a remake of Titanic shot in the Sahara. It’s something that was pitched to me by some of the young kids in Agadez. That wasn’t something I would’ve necessarily arranged. By doing Purple Rain, maybe we kind of introduced this idea of the remake. Some of the kids who were involved with the Purple Rain remake just really love Titanic, primarily because Titanic is something they grew up with—it’s this love story. So they’ve written a script that replaces the boat with a truck transporting migrants. It’s great. I mean the parallels, they work. It hits a rock buried under the sand.

Some of the fun about working on these things, like the Purple Rain film, we don’t have to be too serious about it—we can just make a go of it and if it works, then it works. At the end of the day, it’s really more for the audience in Agadez and for those of us who worked on it than anybody else. If they’re happy with it in the end, then that’s what I want.

—Nilina Mason-Campbell