It’s for good reason that the music of the Lost Bayou Ramblers is synonymous with Louisiana. Founding brothers Louis and Andre Michot grew up there, and their family has roots in the state stretching several generations back. They were tapped to provide music for the acclaimed film Beasts of the Southern Wild, which was set in Louisiana, and no matter how progressive or experimental their music becomes, its grounding in traditional Cajun music is always clearly detectable. So when the southern part of the state was beset by flooding earlier this month, rendering houses uninhabitable and leaving people without places to sleep or food to eat, the first question on the group’s mind was, naturally, “How can we help?”

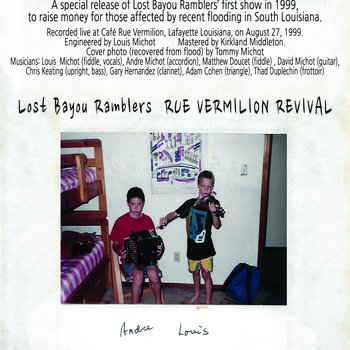

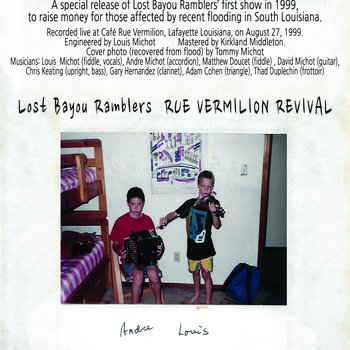

As is often the case with Lost Bayou Ramblers, the answer was found in music. The group has released a live recording of their very first show in 1999, the full proceeds from which will go to benefit those impacted by the flooding. We talked with founder, vocalist and fiddle player Louis Michot about the origins of the project.

Cassette

You were born and raised in Louisiana, and your family has roots there that stretch back several generations. This is kind of a big question, and I apologize for that, but I was wondering: What are some of the things that keep you in the area?

Well, it takes commitment to stay. A lot of people describe Louisiana as a woman who’s both beautiful and full of catastrophe, like Mother Earth itself. But it’s such a beautiful society in South Louisiana, the way that people work with each other, and work with the land, and the number of different people who came together over many generations—so many ethnicities, all coming together to make this new culture. And it’s based in faith in community—that’s really what’s gotten the Cajun Acadian culture so far. You want to talk about the true roots of Acadiana? The Acadians were deported from Nova Scotia in the mid 1700s and completely ripped apart. But through community, and their faith in that, they kept together even through 10 years of exile. We grew up in Louisiana, and that’s been the mother culture of this area, and it’s based in being able to make it through hard situations.

I know a lot of musicians from New Orleans and the surrounding area, and one of the things they talk about is how, in addition to the community in general being tight-knit, the musical community down there is especially strong.

You bring up a really good point, and it’s something that can be hard to see from the inside. But it’s true—everyone works together. We call each other for gigs, people play in multiple bands; if our band can’t make a gig, I’ll try to give it to another band. Most of our work comes from real organic grassroots networking, and that’s how our band has been doing it for 17 years. It’s an interesting model, because it doesn’t necessarily fit the national music model. We’re lucky to have a sustainable operation that can continue to grow.

One thing I’ve noticed about your music is that, no matter how far afield you go musically, it’s always rooted in what could loosely be considered ‘traditional Cajun music.’ Do you see it as part of your responsibility to be ‘musical preservationists’?

I think it’s rooted in necessity. To learn the music, you really have to start at the traditional level, and learn the intricacies and the musical language before you can expect to make a contribution to it. And we’re actually known as one of the more progressive bands, in that we take the most chances and try different things that maybe aren’t traditional. But, at the same time, I believe that the traditional musical form and language is really where it’s at, beauty-wise. Even the language itself—the French, the melodic languages—that’s the tradition, and that’s the important part. Whether or not you’re playing it like exactly the people before you, keeping that language going is where the beauty is. So as experimental as we get, we’ll always see ourselves as a traditional Cajun band.

Vinyl LP, T-Shirt/Apparel

You’ve been doing this for 17 years now. What were some highlights for you along the way?

The first one was the unexpected Grammy nomination [for 2008’s Live: A La Blue Moon]. We recorded a live album as a side note while the producer was in town, and ended up getting a Grammy nomination out of it. That was pretty awesome. The next thing that comes to mind is Beasts of the Southern Wild. That was just a huge ride. It was such an amazing movie, and our contribution was so small, but where my voice fits into the movie, and that song in general—[director Benh Zeitlin] had a real vision of what he wanted, and he wanted my voice on that song. That is just such a beautiful movie, and to me one of the highest artistic representations that Louisiana has had in a long time.

I actually wanted to ask about your work in that film. How did that come about? You mentioned the importance of relationships earlier in the conversation—was this a result of a personal relationship?

I think [the director] had seen us play, and he’d seen us sing ‘The Bathtub Waltz’—that’s the basis of ‘The Bathtub,’ the song I sing in the movie. And that’s exactly what he wanted—that song. It was really a result of him being at our shows in New Orleans and appreciating what we’re doing.

You alluded to him having a “real vision” of what he wanted for the song—was he very hands-on when it came time to record it?

This was a pretty special one, because when we’re in the studio making our own music, it’s on us to make something new. But when you’re recording for a film, they know exactly what they want. And they wanted acoustic instruments, they wanted this song at this tempo, in this key, and they said ‘Do it just like you do it live.’ And, boom, there it was. It was something we could do first pass with no problem. It was just performing traditional Cajun music, which is what we do best. They took that and scored an entire orchestra around our performance, basically. We had the easy part! We had the first two hours in the studio. They had the next year.

You’ve also developed a relationship with Gordon Gano of the Violent Femmes over the years. I’ve heard the “urban legend” of his first live performance with you guys—I was wondering how true that story is.

[Laughs.] So, we were playing [New Orleans venue] d.b.a. all the time, and we had been adding his riff from ‘Blister in the Sun’ into our song ‘Oh Bye,’ just as like a little transition. And then one night, as soon as we started playing the riff, he jumped on stage and said, ‘You mind if I sing?’ Now, I didn’t know who it was, I didn’t know what he looked like, so I was just like, ‘OK, some guy is gonna come sing ‘Blister in the Sun.’ And then he started singing, and it was like ‘Ohhhhhhh. OK!’ And then we didn’t know what to do! Because we’d never gone past the first riff—we didn’t even know what the second chord was. It turned out we were in the complete wrong key. So he called out the chords on the spot, and we played the whole song to complete success. That’s how we met him, and that’s how it’s been ever since—spontaneous and last minute. We don’t have to talk about it much, he’ll show up when he says he’s gonna, and that’s it.

Compact Disc (CD)

I want to talk specifically about this fundraising project you’re doing. First things first, though: How are you guys doing down there?

Well, our road took on three feet of water, so everyone was stuck for a while. That was the case many places—you didn’t know where you could go and where you couldn’t. My dad’s house, which is our family camp, took on two feet of water. And it’s nasty, it smells—it’s a toxic environment, really. Once the water leaves, if you don’t deal with it immediately, it becomes toxic. Just dealing with the fact that your house has become poisonous—it’s intense. There’s this mentality around the whole area—you feel it. And everyone who is OK, everyone who didn’t get flooded, they’re helping the ones who did. And that’s what makes it better. People are cooking, people are driving around with pots of red beans and rice, asking ‘Are y’all hungry? You’ve all been working—here’s some food.’ They’re just trying to make it feel more human, more real—less like a disaster. Right across the bayou from my dad’s camp is Dockside Studio, which is where we recorded our later albums. That took on two feet of water, too—which is just enough to have to completely redo everything. I’ve been over there about three or four days this week, and it’s a lot of work. Luckily, Dockside has helped so many musicians—they’re just the most hospitable studio—that everyone came out to help as much as they could to clear that place out and have it disinfected. Everyone pulled together. You couldn’t even get across the bayou by car, so I had to take my boat from the studio and paddle to my dad’s camp to try to clean that up. This is eight days later, and we’re still dealing with a lot of this.

As far as the fund-raising aspect of this album goes, who are you partnering with on this release?

Everyone’s been saying, ‘How can I help.’ People have so much sympathy after Katrina, they just ask ‘Where can I donate?’ So I asked a few people who they’re working with. I think everyone’s still just trying to get through right now. We had picked out a few organizations that we would like to donate to, and right now the idea is to split the money a few ways. The first is the Second Harvest Food Bank, which has a chapter in New Orleans and a chapter in Lafayette. They repurpose food to feed the poor on a regular basis. They’re doing a lot of flood relief for people who don’t have the resources to go eat at a restaurant while their kitchen isn’t functioning. There’s also The Community Foundation Acadiana. They’re linked up to most of the non-profits in the area, and they disperse funds to all kinds of organizations. They have a flood relief fund going, and I’ve worked with them before, and they’ve helped a lot of people. And then, thirdly, there’s Vermilionville, which is a historic village with a lot of old houses from the area. They keep a lot of traditional art going, and really promote the language and take care of Bayou Vermillion. So the third place we’d like to give to is Vermilionville, because all of their historic houses flooded.

Vinyl LP, T-Shirt/Apparel

All of this really goes back to the idea that we started with—that deep-rooted sense of community and family.

That’s how all of this is happening. You’ve probably noticed the lack of media coverage. I was watching the national news, and they talk about it for about four or five seconds. That’s when I realized that we’re taking care of ourselves down here. We have the ‘Cajun Navy’—that’s anyone who has a boat! I was talking to Matthew Doucet, who’s the second fiddle player on this recording and is also the son of Michael Doucet. He’s a sheriff’s deputy, and he was telling me how he’d been rescuing people for about 48 hours straight. He had to rescue a woman in labor in a Humvee. They had 755 calls that were anywhere from one to 20 people each who needed to be rescued. Most of it was done by people with boats coming out and asking, ‘Where can I go?’ They rescued thousands of people. It’s community coming together. Everyone’s doing their part. And that’s where this whole idea came from. We just want to do our part.

—J. Edward Keyes