Egyptian band Al Massrieen

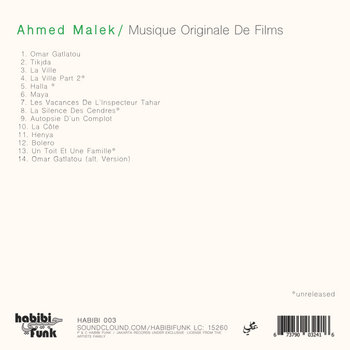

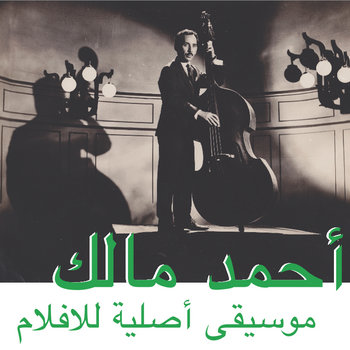

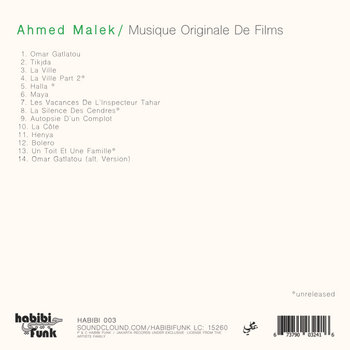

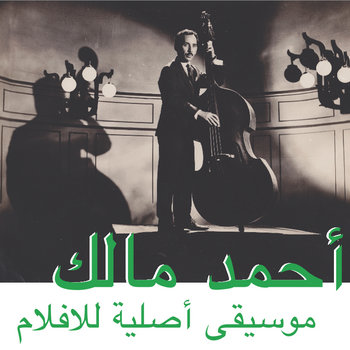

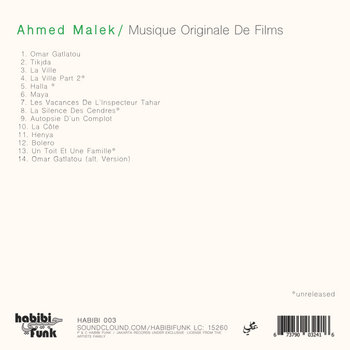

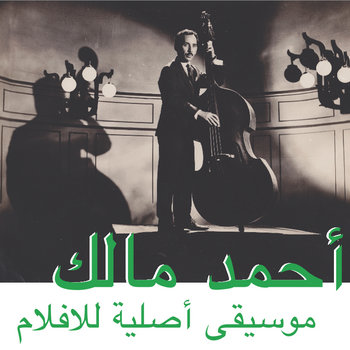

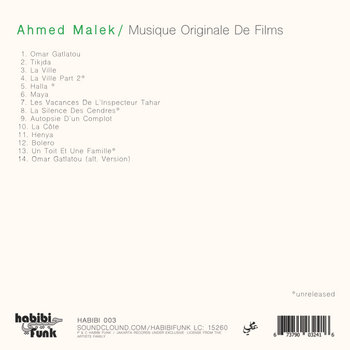

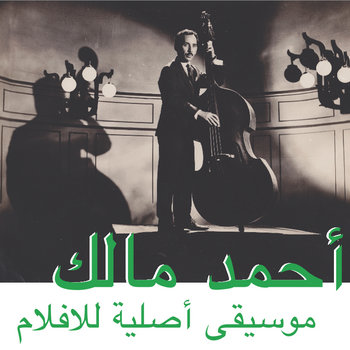

Though Algerian composer Ahmed Malek was an established musician in his country—he passed away in 2008—and also the long-time conductor of the Algerian Television Orchestra, his music had largely been condemned to obscurity. Getting it back on wax has taken a bit of persistence. On May 14th, the Berlin-based imprint Habibi Funk will release Musique Original De Films, a collection of Malek’s film music. Written during the ’70s, the music has stylistic parallels to popular soundtracks of the era, particularly the work of Italian composer and spaghetti-western maestro Ennio Morricone. Yet it is also very much a product of North Africa. The songs are moody and slightly melancholy, but also surprisingly groovy. They fuse Arabic melodies and jazz harmonies with Latin-style rhythms and the odd scrap of psychedelia. Though the release is modeled after Malek’s ultra-rare 1978 LP of the same name, it’s not quite a reissue; the new LP has been enhanced with a number of previously unreleased recordings.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

A co-owner of the Berlin-based Jakarta Records—which releases contemporary hip-hop and dance music—Jannis Stuertz founded Habibi Funk in order to focus on reissuing the rare North African funk and soul records that he had been buying while traveling the region. “There used to be an artist on [Jakarta] called Blitz the Ambassador and he played a festival in Morocco. I went along and stayed a couple of extra days,” says Stuertz. “Even back in the days when I was just traveling in Thailand or India, I would see what kind of music was around from the ’70s, to see if there was anything that might interest me. I did the same in Tunisia and Morocco and I found a lot. But then when you Googled the artists, there was no information whatsoever.”

During the ’60s and ’70s, the gravitational pull of American soul, funk, and R&B was strong. Around the world, garage bands squirreled away gig money to record and press small run singles and albums of their own slightly-tweaked takes on James Brown’s formula. Few found much of an audience. In the last decade, a number of labels have stepped up to document these scenes, releasing countless compilations of Thai funk, Cambodian pop, and Nigerian psych-rock. However, Stuertz felt like the music he was finding in North Africa was under-represented. “There was quite a scene of local artists in the Arabic world that blended Arabic traditions with western soul-funk,” he says. Drawing from his collection, he recorded a handful of DJ mixes and posted them online. When those met with a positive reaction, he decided to go ahead with a label.

Jannis Stuertz of Habibi Funk Records

Jannis Stuertz of Habibi Funk Records

It’s one thing to make a passionate personal connection to a rare or obscure record. It’s another to undertake the relatively onerous process of reissuing it—securing the rights, procuring a high quality master, pressing a vinyl record. And in Habibi Funk’s case, there was the added difficulty of tracking down obscure artists in a distant land. “I guess it’s more like a logical step for somebody like me who already has been running a label. I already knew what steps it took,” says Stuertz. “I guess the thing that had me make the decision to invest this type of energy was that there didn’t seem to be anybody doing it for that particular region.”

Habibi Funk’s first release was a reissue of Alech, the lone two-song single by an early ’70s Tunisian soul band called Dalton. That one was easy, thanks to modern social networking. “For Dalton, I just checked the back sleeve and looked at who wrote it. He was on Facebook,” says Stuertz. A reissue of Al Zman Saib—the first album by gonzo Moroccan soul singer, Fadoul—proved more challenging. A Moroccan band, Golden Hands, was able to point Stuertz toward an old scenester who had been close to the singer. That man directed the record label owner to Fadoul’s old neighborhood, which yielded information on his former employer, who ultimately provided an address for the singer’s daughter. The process took a few years.

Though Malek’s music was somewhat less obscure, it took a particularly lucky break for Habibi Funk to locate the composer’s next of kin. While DJing in Beirut, Stuertz told a friend of his desire to reissue Malek’s music. Though she had only one contact in Algiers, she said that she could ask the individual if they had any idea on how to seek out the composer’s family. As it turned out, they didn’t have far to go; Malek’s daughter lived next door to her contact. “Algiers is a city of 1.5 million people, and the one person we had a contact with ended up being the neighbor,” says Stuertz. “We just got incredibly lucky.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The quality of the recordings is another hurdle for Habibi Funk. According to Stuertz, it’s extremely rare to find a useable master tape. As a result, Habibi Funk’s reissues are often pulled directly from clean copies of the original records. Though they have plenty of lo-fi mystique, it sometimes takes a bit of studio magic to make them listenable. “If the initial recording is shit, it will not sound so great,” explains Stuertz. A lot of these people worked on very limited budgets—they could have bought half a day in the studio. So, it’s not going to sound like a proper studio production,” he explains. “There’s a Fadoul track where there’s a very heavy bass line for the first two minutes of the song, then you can hear [the band] realize that it’s too prominent and they turn it down without starting over. In the reissue it’s not that obvious because we fixed it, but it tells you a lot about the recording [session]. Some of the recordings are really punk rock in the way they sound.”

Yet, with Malek’s recordings, Stuertz lucked out again. When he visited Malek’s daughter, he discovered that she still had a number of the composer’s master tapes, many containing unreleased music that the label has plans to reissue in two subsequent collections.

“Ahmed Malek’s music was much more versatile than the first reissue will show,” says Stuertz. “We came home with 30 master tapes. Some of the music is similar in the sound to this reissue, but there will also be a third album of early electronic music. There’s nearly two hours of material of that nature. It will all be released one way or another.”

These synthesizer compositions are stripped down and simple—a primitive drum machine paired with vibey analog strings—but deeply hypnotic. Where Malek’s film music has some sonic precedent in the conventions of pulpy ’70s film scores, the synthesizer music is particularly otherworldly in its blend of cosmic new age tones and Arabic melodies.

Habibi Funk has a few other projects on the horizon as well, including a recently re-discovered music by Fadoul and the Egyptian band Al Massireen. Despite all of this, Stuerz admits that, when he’s travelling, digging up new records is not always the first priority. “There’s definitely people who do it more hardcore than me. I know of diggers who go to West Africa and Ethiopia who have full-page ads in newspapers,” he says. “As I’m not a records dealer, I don’t do the digging part. I like to sit in coffee shops and do nothing, just walk around. When I’m traveling, it’s a relevant part of what I do, but it’s not the only thing.”

—Aaron Leitko