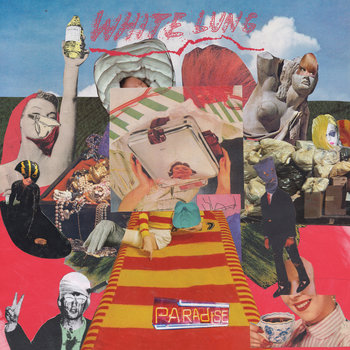

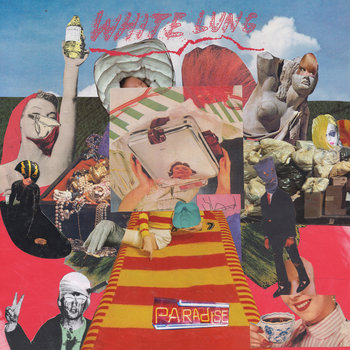

The title of Paradise, the follow-up to White Lung’s searing 2014 album Deep Fantasy, contains an element of autobiography. Over the course of the last two years, frontwoman Mish Barber Way relocated from her native Vancouver to sunny Los Angeles, then got married, then moved to the suburbs. Which is ironic, given that Way, who also pens a weekly sex column for Vancouver alt-weekly Westender and investigative pieces for Vice’s Broadly, spent most of the record’s creation trying to figure out how to reveal less of herself.

“People expect you to be autobiographical,” she says. “It’s kind of nice to not do that. When you write a lot, there’s a point where you’re like, ‘I don’t have anything more to say.’”

As a result, Paradise contains a number of songs written from the perspective of other people. In “Kiss Me When I Bleed,” Way adopts the point of view of a “rich girl” living in a trailer park, who falls in love with a garbage collector. The haunting “Below” is based on a quote by Camille Paglia.

Cassette, Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The group paired Way’s new approach to lyrics with a different philosophy on songwriting, which Way describes as “The Oasis ‘don’t be afraid of the hook’ kind of thing.” The result is the group’s most melodic, ambitious, immediate album to date.

During a short stint in New York in early April, we took Way to the Museum of Modern Art, where we peered into tiny houses in the Japanese Constellation exhibit (“I just have the urge to flick them over,” she deadpans), and pondered old psychedelic rock posters.

In your recent interview with Annie Clark, you said you were content, and that things were going well, and how that’s not good for songwriting. It’s a weird paradox.

It’s bad for any kind of writing. You need to feel good to feel bad [so you can] know the difference. I think ultimately it ended up being good, because instead of writing another record whining about my life, I said, ‘Alright, I’m going to write from different perspectives. I’m going to write characters. As me, I can’t say these things. But as this character, I can.’

It ended up being kind of freeing. Especially for the lyrics. Because my life is good! I have nothing to complain about. I’m not going to write a bunch of love songs for my husband. There’s only so many ways to say that—though he’d love that. I just got to write outside myself, which was cool and fun.

What kinds of characters were you drawn to?

The song “Sister” was written from the perspective of Karla Homolka. Do you know her? She and her husband were known as the ‘Ken and Barbie Killers.’ They were Canadian killers in the early ’90s—early 20s, blonde, beautiful. But Karla helped her husband, Paul, rape and murder and torture three young girls, including her own little sister. And I got really obsessed with Karla, because I was writing an essay for Broadly about the psychology behind women who help their husbands rape and murder and torture people.

So I wrote the song “Sister” from the point of view of Karla apologizing to [her sister] Tammy for being a part of her death. I have two little sisters. The idea of offering up my little sister’s virginity to the man I supposedly love is the most…it’s insane. She was participating happily. She was malicious. I wrote this song, her apologizing to her sister and the other girls. She’s probably not sorry. Her face is on the record cover, she’s really small. It’s from when she went to the police, and that’s when they got busted. I hope she sues me so I can ask her if she’s sorry.

With [the song] “Dead Weight,” I’ve been obsessed with motherhood and childbirth and contemplating a lot of that in my life. You get married to the person you love, and you’re like, ‘Oh, now I understand why people think about kids.’

Cassette, Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Had you never thought about that before?

I had, but I never thought that it was in my trajectory. I just didn’t think that it was something that was going to happen. I just didn’t know. You meet someone you would actually have kids with, and it changes things. So in the song “Dead Weight,” I was imagining this woman who’d had a miscarriage, but really wanted to have a baby. So I was singing from her perspective, that desperate need to follow your biology and be maternal and reproduce, but your body keeps letting you down. That ultimate sadness of not being able to have a baby when you want to, or losing one constantly.

“Demented” is Fred and Rosemary West fighting back and forth. They killed a lot of their own kids. But their daughter who survived, who [Fred] molested for years, she recently spoke out about her parents. Imagine your parents were serial killers, and one of them molested you. How would you live? How would you have normal conversations with people?

Right. How can you expect to be normal?

I would love to be a therapist who works with people like that. I’m sure it would be the most challenging job in the world. I was thinking about wanting to go back, eventually, and do schooling to be a relationship and marriage counselor. I like figuring that stuff out with people, and I think it would be nice to see two people who actually want to try at their relationship. [Pause] I see you still keep notes with a pen and paper.

It’s the only way I can do it.

The only way I can write lyrics is on pen and paper and Lars [Stalfors], our producer, said to me, ‘I can’t believe you’re writing lyrics with pen and paper, I haven’t had someone do lyrics with a pen and paper in years.’ What, people write lyrics on their phone? Say I’m doing this lyric, and I don’t like it and cross it out. I can still see underneath what I crossed out. Maybe the idea is really cool, but you just didn’t like it in that moment.

It’s so great to go back through journals, too. I grew up a figure skater, and I had my figure skating journal. I was very hard on myself, so I would say everything I did that day, plus everything I did wrong or had to fix or do better. Then I had my actual writing journal, and a book where I wrote short stories. But I look at my figure skating journal and it’s a 12-year-old being so mean to herself. What was wrong with me? Individualized sports like that are great for teaching self-discipline, but not for treating yourself with respect.

Do you still think about skating?

I still think about it. Like, ‘Wow, the things that I used to be able to do.’ Like spin around with my leg pulled behind my head. I can’t believe that I could do that. But I wasn’t fearless enough to be a figure skater. You have to be fearless. I got very scared of jumping when I reached a certain age, and would psych myself out and freak out. When I got older and more conscious, I stopped enjoying it because I was so afraid of jumping. You have to be totally, stupidly fearless.

I was never a reckless kid. I was always afraid of going down the slide, I didn’t like the jungle gym. I didn’t even want to ride a bike. When my dad taught me how to ride a bike—a two wheeler, not with training wheels—I screamed, ‘You’re trying to kill me!’ so loudly that our neighbors called the police. They thought he was trying to kill me. I was freaking out. I just want to sit and color, don’t make me do anything scary.

You have to be fearless to do what you do, though.

That’s a different kind of thing. It’s psychological. I was talking to someone who does work on really tall buildings, like cleaning windows on a building that has 80 floors. And I wouldn’t be able to do it. I would have a panic attack and fall to the ground. And they were like, ‘Are you kidding me? How can you stand in front of people and command their attention?’

I’m not afraid of getting emotionally damaged. No problem. I can take it. But physical stuff scares me. My husband made me go on a roller coaster and I hated it. It’s not fun for me. I’m afraid I’m going to fly out, it’s too fast! I guess we all have a different thing that isn’t scary to us. And everyone’s good at something.

—Paula Mejia

Photos by Rick Rodney